Audio By Carbonatix

From Jomoro through Ahanta West to parts of Nzema East, the shoreline of Ghana’s Western Region tells a troubling story. Each year, usually between June and October, and for more than a decade, the sea changes character.

Where fishing nets once returned with baskets of fish, they now come back heavy with brown seaweed.

For many fisherfolk and coastal residents, this is not merely an environmental nuisance; it has become a daily battle for survival during these months.

The culprit is sargassum a type of free-floating brown algae that thrives in warm ocean waters and travels vast distances. Coastal communities recognize it instantly: thick brown masses carpeting beaches, clogging nets and outboard motors, and rotting along the shore.

“It’s not fish we bring home anymore,” a fisherman from one affected community says.

“The smell makes it hard to stay close to the shore, let alone sell our catch.”

The infestation has reduced fishing activity, slashed incomes, and discouraged tourism in areas once known for their scenic beaches. In communities such as Aketakyi, Essiama, Akwadi and Miamia, within Jomoro and Nzema East, piles of seaweed sometimes rise more than four feet high, forcing families to rethink how and where they live.

Fisherman Isaac Egan, a canoe owner, gestures helplessly toward his boat stuck at sea.

“Look at my canoe stuck over there. For weeks, life has been unbearable for my family. I'm not the only one affected; my colleagues are too,” he says.

“We started seeing these brown weeds when they started this oil thing.”

WHAT CAUSES THE SEAWEED INVASION?

For years, residents have speculated about the cause. Some blame offshore oil exploration, believing heavy machinery and vibrations disturb the seabed and release the seaweed.

“All along I attributed these weeds to oil company activities,” an assembly member from Princess–Aketakyi told JoyNews.

“When I was younger, we didn’t see this. But when oil activities started, that’s when these weeds appeared.”

Scientists, however, say the explanation is more complex.

Dr. Victor Owusu, Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Education, Winneba, explains that much of the sargassum washing up on Ghana’s shores likely originates far away from the Sargasso Sea near the Caribbean and Central America.

“Rising sea surface temperatures and unusual ocean currents are facilitating the movement of seaweed from the Americas to West Africa,” he explains.

“This is not unique to Ghana. Liberia, Sierra Leone and Senegal are experiencing it too.”

Warmer oceans, combined with nutrient-rich runoff from agriculture and industry, create ideal conditions for sargassum to grow offshore before drifting thousands of kilometres across the Atlantic.

WHEN NATURE AND LIVELIHOODS COLLIDE

The timing of the invasion deepens the hardship. Sargassum often arrives during July and August, locally known as the “Mawura” season a period when fish stocks peak and many fisherfolk earn enough to settle debts accumulated over the year.

Instead of fish, nets haul in seaweed. The heavy algae tear nets, clog engines, and make navigation risky. Some canoes remain idle for weeks, pushing households toward unstable alternative livelihoods.

HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

Beyond economic losses, decomposing seaweed releases hydrogen sulphide (H₂S), a pungent gas that causes respiratory irritation and skin itching. Residents describe the stench as overwhelming when seaweed piles up along the beach.

Tourism has also taken a hit, with visitors avoiding beaches covered in rotting algae.

CLEANING UP: A STRUGGLE AGAINST VOLUME

Efforts to remove the seaweed reveal another layer of the crisis.

“We used to sweep here every day,” a disgruntled woman in Aketakyi explains.

“But looking at the volume now, there is nothing we can do as a community.”

Another resident, a former member of an eight-person cleanup team in Aketakyi, says they once volunteered to sweep the shore regularly.

“We don’t even go fishing, but when fishermen stay home because of the seaweed, we are also affected,” he says.

“When the volume increases, we simply cannot cope.”

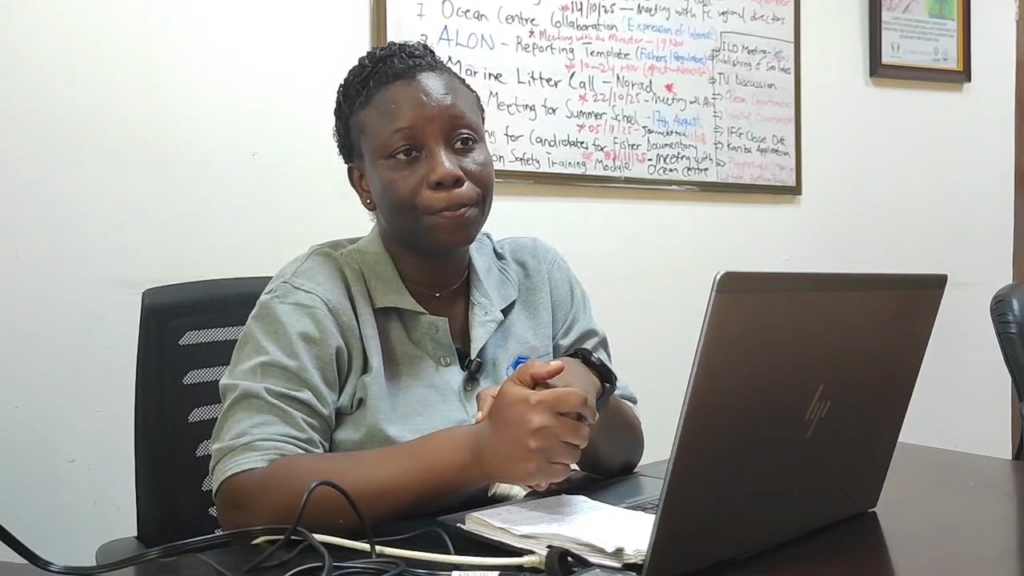

Anita Boateng Ameyaw, Project Coordinator for the Ocean Justice and Livelihoods programme at Friends of the Nation, confirms the challenge.

“Communities and assemblies rely largely on manual cleanup—shovels and wheelbarrows,” she explains.

“But the volume of sargassum makes this approach unsustainable.”

Dr. Owusu agrees, noting that even in the Caribbean, complete removal has proven difficult.

“This is a transboundary problem,” he says.

“Even if Ghana cleans its beaches, seaweed from neighbouring countries can still wash ashore.”

SCIENCE, POLICY AND THE ROAD AHEAD

Research institutions, including the University of Cape Coast and the University of Ghana, are studying the phenomenon, but scientists caution that eliminating sargassum entirely is unlikely.

Instead, experts advocate adaptation, early response, and value addition. In parts of the Caribbean and Asia, sargassum is processed into fertilizers, compost, animal feed, and industrial inputs.

Ghana’s National Adaptation Plan and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) emphasize coastal zone management and community-based adaptation. Yet, gaps persist between policy and practice.

“Local institutions lack resources, equipment and funding,” Dr. Owusu notes.

“Seaweed adds pressure to already overstretched coastal management systems.”

TOWARDS A FUTURE THAT WORKS

Despite the hardship, coastal communities remain resilient. Communal cleanups, burial of decomposing seaweed, and shared coping strategies reflect determination but also desperation.

“We need more than shovels,” one fisher says simply.

As the seaweed season approaches each year, urgent questions remain:

• How can communities prepare better?

• What technologies can Ghana invest in?

• Can research turn this ecological challenge into economic opportunity?

• How can national and regional coordination be strengthened?

The sea may no longer behave as it once did, but for Ghana’s coastal communities, learning to adapt before livelihoods are washed away has become a matter of survival.

This article is written as part of a collaborative project between JoyNews, CDKN Ghana, and the Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability at the University of Ghana, with funding support from the CLARE R4I Opportunities Fund.

Latest Stories

-

Ghanaian Passport for US YouTube star IShowSpeed signals new era of State diplomacy

1 minute -

Bawumia welcomes Adutwum, Kwabena Agyepong to his home after victory in NPP primary

1 minute -

President Mahama arrives for World Governments Summit 2026 in Dubai

9 minutes -

GACL MD commends Air Tanzania for launching Accra route

12 minutes -

New AASU leadership promises stronger voice for African students

13 minutes -

Bawumia urges early collaboration to reclaim lost NPP seats

15 minutes -

National Chief Imam congratulates Bawumia on NPP flagbearer victory

18 minutes -

Opoku-Agyemang, Hanna Tetteh, and Martha Pobee named among 2025 100 most influential African Women

21 minutes -

Kwabena Bomfeh urges NPP unity to boost Bawumia’s 2028 presidential prospects

22 minutes -

Bawumia calls for continuous coordination to secure 2028 victory

24 minutes -

I expected Kennedy Agyapong to win NPP primary – Stephen Amoah

28 minutes -

Atebubu: Suspected notorious armed robber shot dead by police

31 minutes -

Sammi Awuku urges NPP supporters to rally Bawumia ahead of 2028 elections

32 minutes -

Kpandai NDC executives distance themselves from supporters’ protest following Supreme Court ruling

33 minutes -

6 revelations from the NPP’s historic 2026 presidential primary

36 minutes