Audio By Carbonatix

In 2022, Ghana found itself in the midst of a severe economic crisis that forced the government to seek a $3 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

While rising debt and fiscal mismanagement were major contributors, a critical yet often overlooked factor was the role of bond vigilantes, investors who lost confidence in Ghana’s financial stability and dumped the country’s bonds.

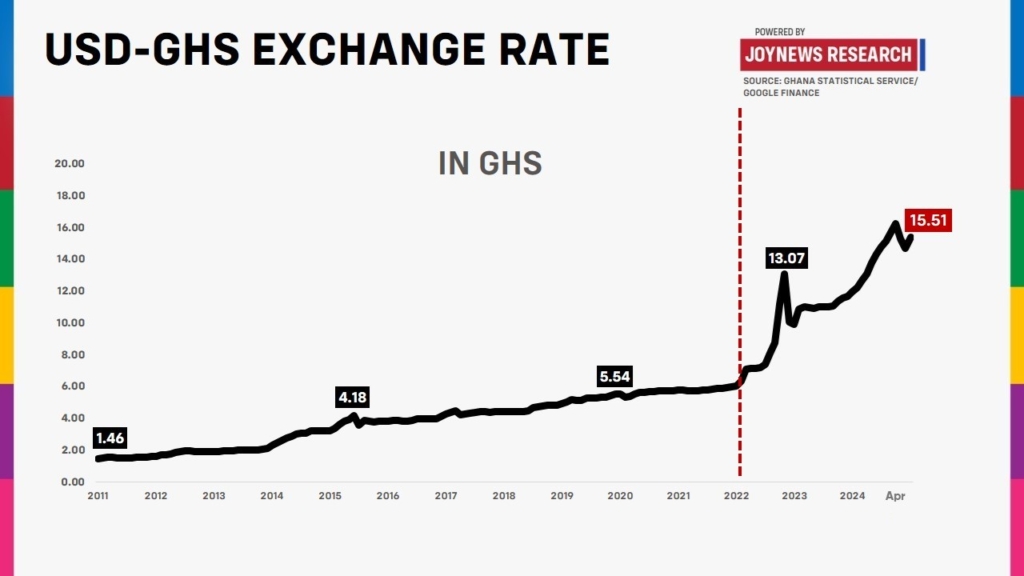

This selloff triggered a surge in borrowing costs, a rapid depreciation of the cedi, and ultimately, Ghana’s financial distress.

Let’s explore how these bond vigilantes influenced Ghana’s economy, their role in the 2022 crisis, and the broader implications for fiscal policy and investor confidence.

Understanding Bond Vigilantes and their Influence

A bond vigilante refers to investors who sell off government bonds when they believe a country’s economic policies are unsustainable.

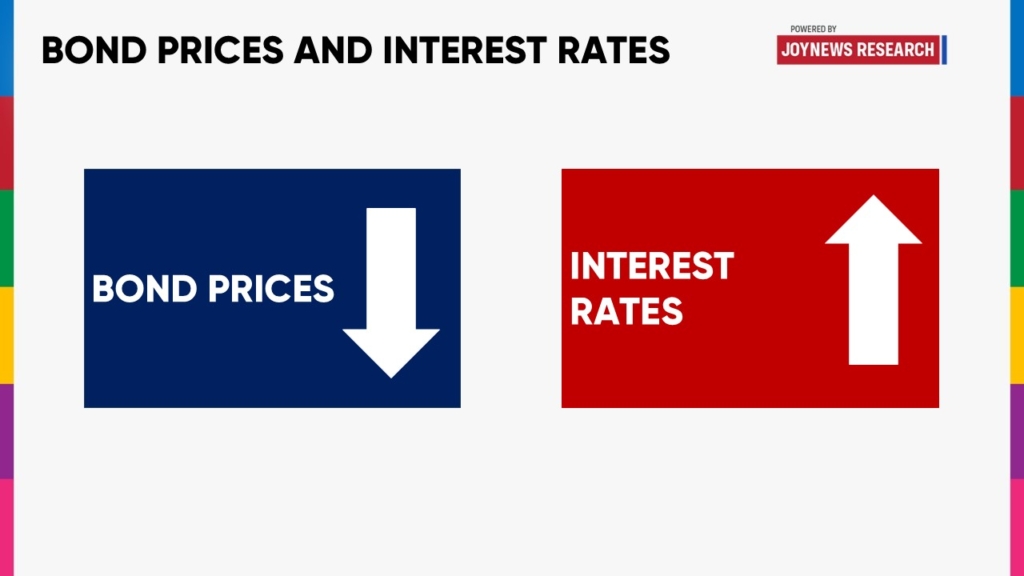

This leads to falling bond prices and rising interest rates, making it more expensive for the government to borrow. Bond vigilantes act as a check on fiscal irresponsibility by increasing borrowing costs when they detect excessive deficits, inflation risks, or debt distress.

Think of bonds like old CDs with fixed interest rates at a bank.

- If banks raise interest rates, new CDs will offer higher returns. Your old CD, which pays a lower rate, becomes less attractive, so if you wanted to sell it, you'd have to offer a discount (lower price) to attract buyers.

- If banks lower interest rates, your old CD with a higher fixed rate becomes more valuable, and people would be willing to pay extra (a higher price) to get it.

Bonds work the same way:

- When interest rates go up, new bonds pay better rates, so old bonds lose value.

- When interest rates go down, old bonds with higher rates become more valuable.

This phenomenon is common in advanced economies like the U.S. and the UK, where bond markets are large and influential. However, Ghana’s crisis showed that even in developing economies, investors—both foreign and domestic—can significantly impact financial stability.

How Bond Vigilantes Triggered Ghana’s Crisis

Ghana had been borrowing aggressively for years, financing infrastructure projects and government programs through:

- Eurobonds (loans from foreign investors in dollars).

- Domestic bonds (loans from local banks, pension funds, and individuals in cedis).

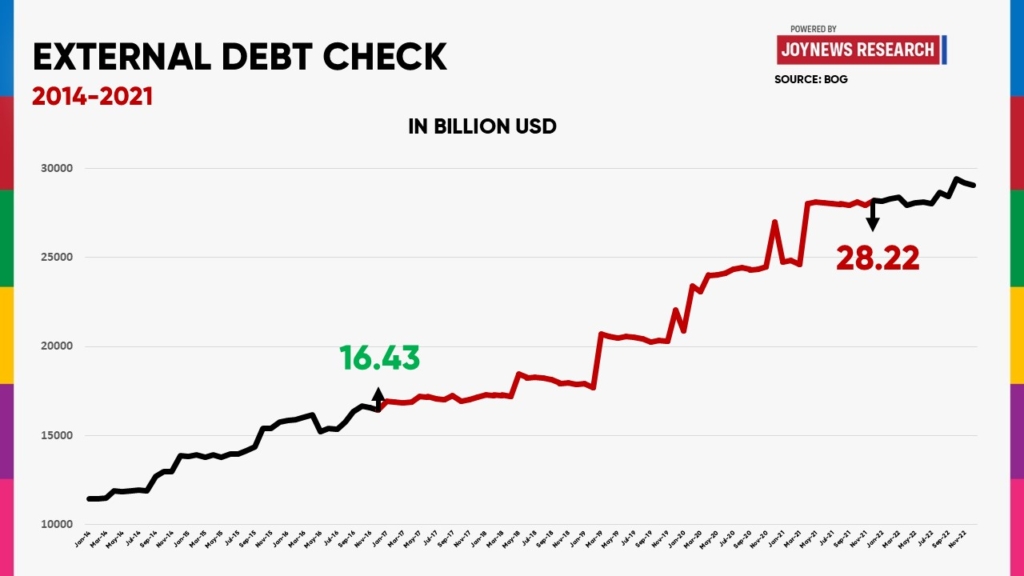

Between 2017 and 2021, Ghana issued multiple Eurobonds, increasing external debt.

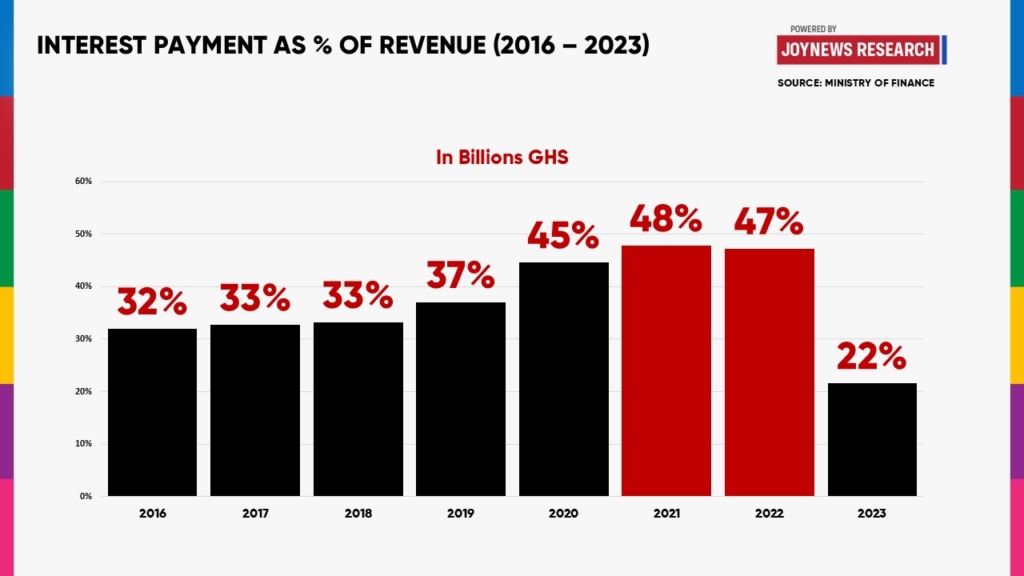

While this initially helped finance development, it also raised debt servicing costs—by 2022, interest payments alone were consuming nearly half of government revenue.

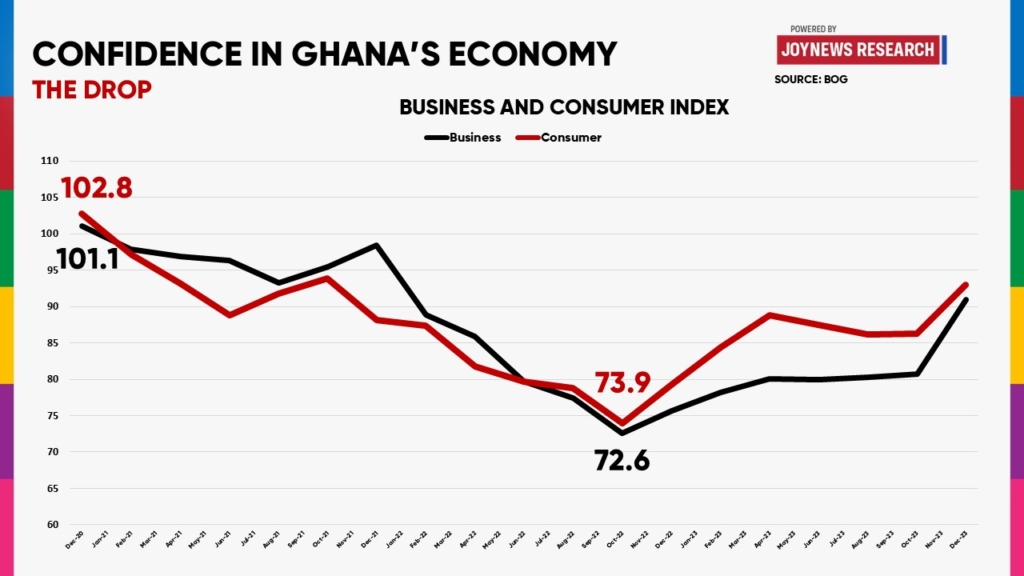

Loss of Investor Confidence & Bond Selloff

By early 2022, several warning signs made investors nervous about Ghana’s ability to repay its debts:

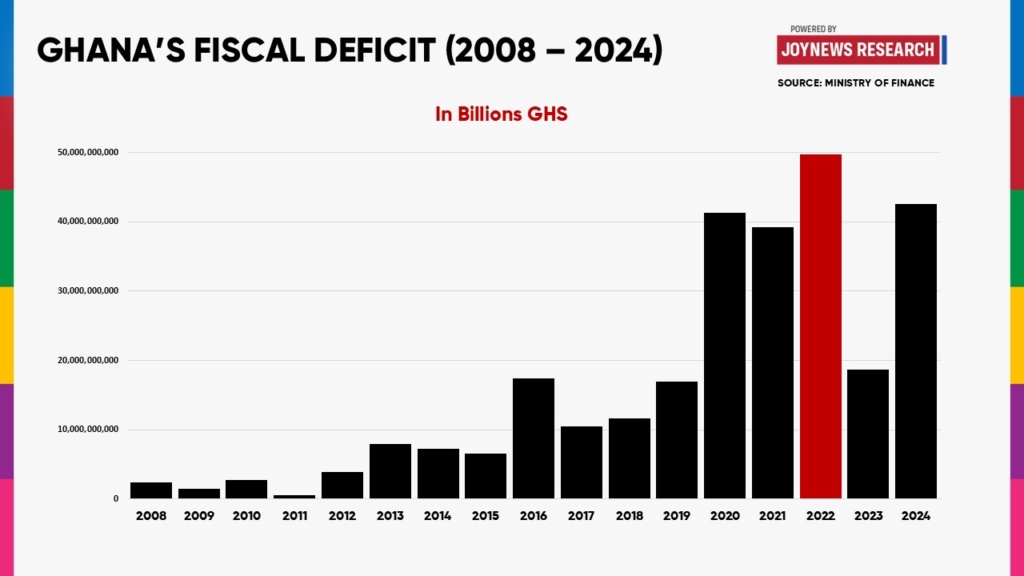

Soaring fiscal deficits are due to excessive spending.

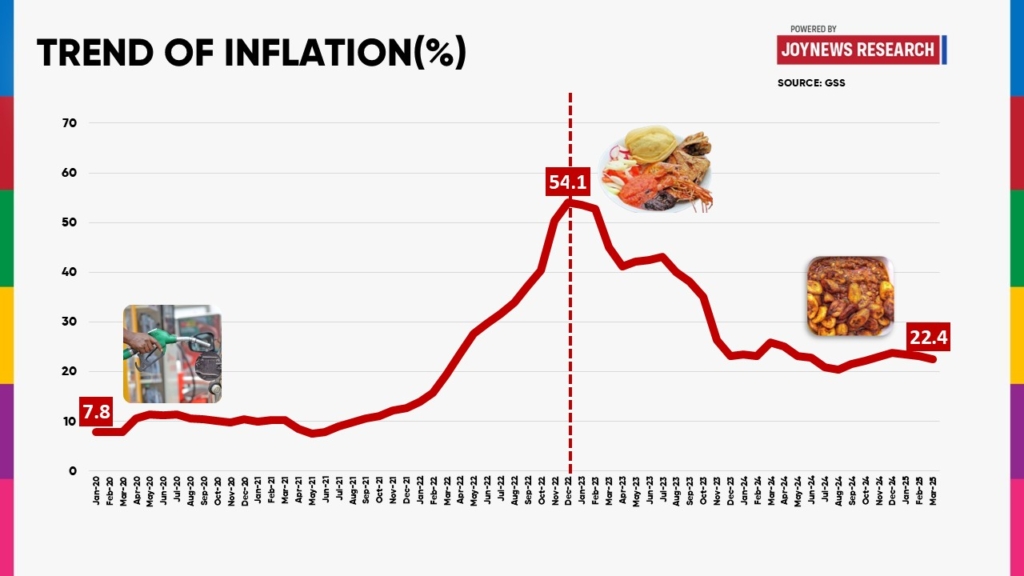

Rising inflation and currency depreciation.

As a result, both foreign and domestic investors began selling off Ghana’s bonds. This led to:

Bond prices are crashing, making it more expensive for Ghana to issue new bonds.

Interest rates (yields) on bonds are spiking—for instance, Ghana’s Eurobond yields surpassed 30%, meaning borrowing from international markets became impossible.

Capital flight, as foreign investors pulled out their money, worsened the cedi’s depreciation.

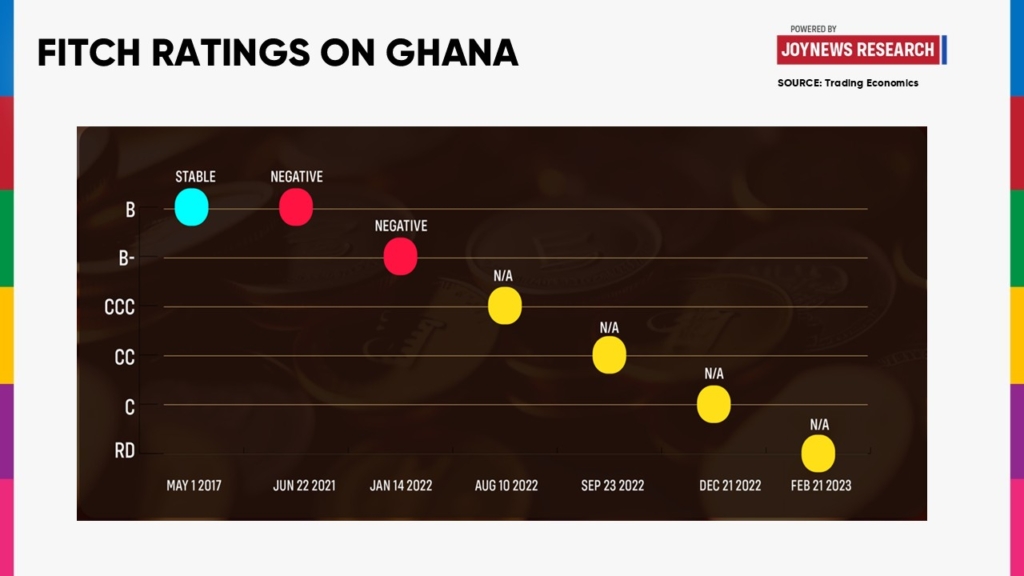

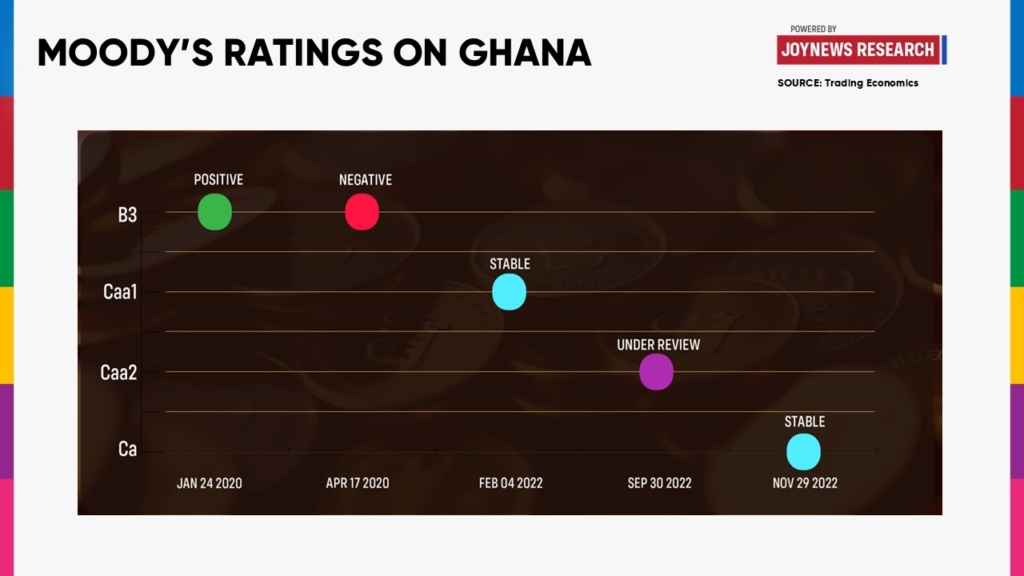

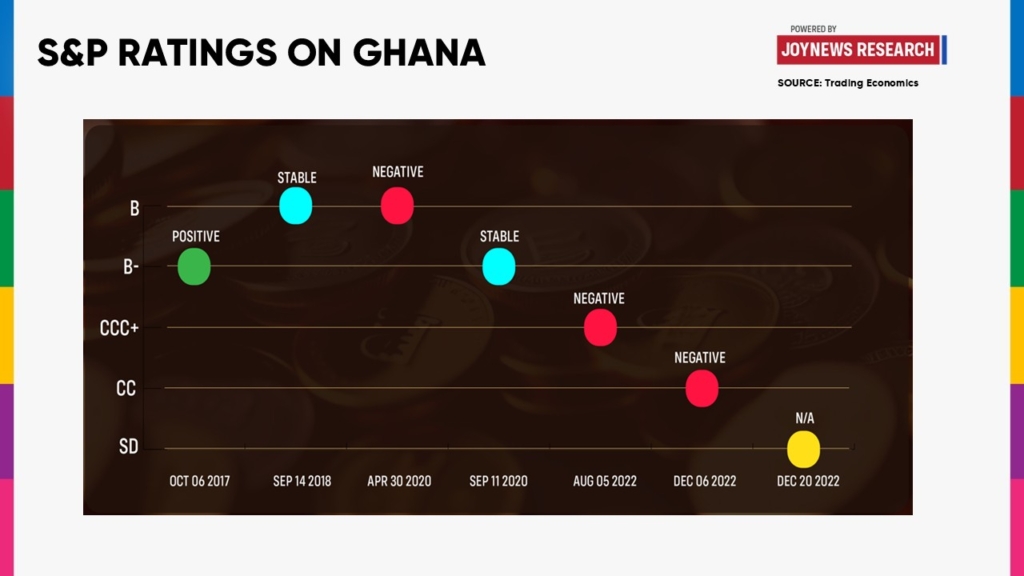

Credit Rating Downgrades Worsened the Crisis

As investors dumped Ghana’s bonds, major credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P downgraded the country’s creditworthiness.

- Ghana was classified as a high-risk borrower, further deterring potential investors.

- The government struggled to secure funding from both international and local sources.

This situation created a vicious cycle—investor panic led to bond selloffs, which led to higher borrowing costs, forcing Ghana into an even deeper financial hole.

Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) & IMF Bailout

By mid-2022, Ghana faced a liquidity crisis—it could no longer afford to service its debts. To avoid a full-scale default, the government had to;

- Restructure its local debt through the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP), forcing local bondholders (banks, pension funds, and individuals) to accept losses.

- Seek an IMF bailout to restore investor confidence and stabilize the economy.

In December 2022, Ghana officially requested an IMF support programme, receiving $3 billion in loans in exchange for committing to fiscal discipline, expenditure cuts, and structural reforms.

Latest Stories

-

Kpasec 2003 Year Group hosts garden party to rekindle bonds and inspire legacy giving

59 minutes -

Financing barriers slowing microgrid expansion in Ghana -Energy Minister

1 hour -

Ghana’s Ambassador to Italy Mona Quartey presents Letters of Credence to Pres. Mattarella

1 hour -

KOSA 2003 Year Group unveils GH¢10m classroom project at fundraising event

1 hour -

Woman found dead at Dzodze

4 hours -

Bridging Blight and Opportunity: Mark Tettey Ayumu’s role in Baltimore’s vacant property revival and workforce innovation

4 hours -

Court blocks Blue Gold move as investors fight alleged plot to strip shareholder rights

4 hours -

Nana Aba Anamoah rates Mahama’s performance

4 hours -

Ghana selects Bryant University as World Cup base camp

5 hours -

Nana Aba Anamoah names Doreen Andoh and Kwasi Twum as her dream interviewees

5 hours -

Religious Affairs Minister urges Christians to embrace charity and humility as Lent begins

6 hours -

Religious Affairs Minister calls for unity as Ramadan begins

6 hours -

Willie Colón, trombonist who pioneered salsa music, dies aged 75

7 hours -

Ga Mantse discharged from UGMC following Oti Region accident

8 hours -

Guardiola tells team to chill with cocktails as Man City pile pressure on Arsenal

8 hours