Audio By Carbonatix

When Pte Oleksander Bezverkhny was evacuated to the Feofaniya Hospital in Kyiv, few believed he would live.

The 27-year-old had a severe abdominal injury and shrapnel had ripped through his buttocks. Both his legs were amputated.

Then, doctors discovered that his infections were resistant to commonly used antibiotics – and the already daunting task of saving his life became almost hopeless.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is when bacteria evolve and learn how to defend themselves against antibiotics and other medicines, rendering them ineffective.

Ukraine is far from the only country affected by this issue: around 1.4 million people globally died of a AMR infection in 2021, and in the UK there were 66,730 serious antibiotic-resistant infections in 2023.

However, war appears to have accelerated the spread of multi-resistant pathogens in Ukraine.

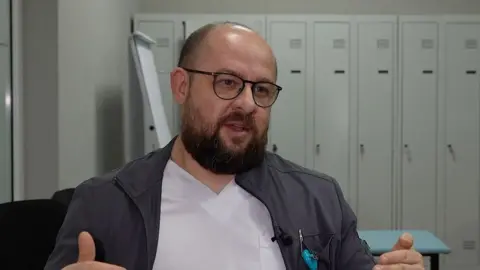

Clinics treating war injuries have registered a sharp increase of AMR cases. More than 80% of all patients admitted to Feofaniya Hospital have infections caused by microbes which are resistant to antibiotics, according to deputy chief physician Dr Andriy Strokan.

Ironically, antimicrobial-resistant infections often originate from medical facilities.

Medical staff try to follow strict hygiene protocols and use protective equipment to minimise the spread of these infections but facilities can be overwhelmed with people injured in the war.

Dr Volodymyr Dubyna, the head of the Mechnikov Hospital's ICU, said that since the start of the Russian invasion, his unit alone has increased the number of beds from 16 to 50. Meanwhile, with many employees fleeing the war or joining the military themselves, staffing levels are down.

Dr Strokan explained that these circumstances can affect the spread of AMR bacteria. "In surgical departments, there is one nurse that looks after 15-20 patients," he said. "She physically cannot scrub up her hands in the required amount and frequency in order not to spread infections."

The nature of this war also means patients are exposed to far more strains of infection than they would be in peacetime. When a soldier is evacuated for medical reasons, they will often pass through multiple facilities, each with their own strains of AMR. While medical professionals say this is unavoidable because of the scale of the war, it only worsens the spread of AMR infections.

This was the case for Pte Bezverkhny who was treated at three different facilities before reaching the hospital in Kyiv. Since his infections could not be treated with the usual medication, his condition deteriorated and he contracted sepsis five times.

This situation is different to other recent conflicts, for example, the Afghanistan War, where Western soldiers would be stabilised on-site and then air-transferred to a European clinic rather than passing through multiple different local facilities.

This would not be possible in Ukraine as the influx of patients has not been seen since the Second World War, according to Dr Dubyna, whose hospital in Dnipro neighbours front-line regions. Once his patients are stable enough, they are transferred to another clinic – if it has room – to free up capacity.

"In terms of microbiological control, it means they spread [bacteria] further. But if it's not done, we're not able to work. Then it's a catastrophe."

With so many wounded, Ukrainian hospitals simply cannot usually afford to isolate infected patients – meaning that multi-resistant and dangerous bacteria spread unchecked.

The problem is that infections they cause must be treated with special antibiotics from the "reserve" list. But the more often doctors prescribe these, the quicker bacteria adapt, making those antibiotics ineffective too.

"We have to balance our scales," Dr Strokan explains. "On the one hand, we must save a patient. On the other – we mustn't breed new microorganisms that will have antimicrobial resistance."

In Pte Bezverkhny's case, doctors had to use very expensive antibiotics, which volunteers sourced from abroad. After a year in hospital and over 100 operations, his condition is no longer life-threatening.

Doctors managed to save his life. But as pathogens grow more resistant, the struggle to save others only gets harder.

Latest Stories

-

Kim Jong Un chooses teen daughter as heir, says Seoul

19 minutes -

Morocco to spend $330m on flood relief plan

25 minutes -

Ghana’s gold output hits record 6 million ounces in 2025, industry group says

27 minutes -

‘I’m a lover boy, not womaniser’ – 2Baba on fatherhood, marriage to Natasha

40 minutes -

Tems becomes first African female artist to have 7 entries on Billboard Hot 100

50 minutes -

Police arrest three for the alleged possession of firearm without license

1 hour -

Suspected robber shot dead by police while fleeing with officer’s vehicle

1 hour -

Head porter charged over mobile phone theft

1 hour -

Tuchel extended England stay for ‘amazing players’

2 hours -

Atletico Madrid put four past Barcelona in Copa del Rey semi-final

2 hours -

Tottenham are ‘not a big club’ – Postecoglou

2 hours -

Nottingham Forest close in on Pereira appointment

2 hours -

England to face Spain and Croatia in Nations League

2 hours -

Sterling joins Feyenoord until end of season

2 hours -

A Tax for Galamsey: Akwasi Acquah slams government for failing to punish complicit officials

2 hours