Audio By Carbonatix

To ask whether Ghana suffers from neo-colonialism is to pose a question that reverberates across the entire post-colonial world, a question that touches the wound that never quite heals.

Neo-colonialism — that shadowy continuation of imperial domination after the flags have been lowered and the governors recalled — operates not through direct political control but through economic leverage, cultural hegemony, and the subtle architecture of dependency.

It is colonialism without colonisers, empire without emperors, domination dressed in the language of partnership and development. By this definition, Ghana’s experience since independence in 1957 presents a case study in the persistence of external control despite formal sovereignty, a narrative of freedom proclaimed but not fully realised.

The economic dimension reveals neo-colonialism’s most concrete manifestations, for it is through the sinews of finance and trade that contemporary domination functions most effectively. Ghana’s relationship with international financial institutions — particularly the International Monetary Fund and World Bank — demonstrates how sovereignty can be hollowed out whilst its shell remains intact.

Since independence, Ghana has entered into seventeen separate IMF programmes, each accompanied by conditions that transferred policy-making authority from Accra to Washington. These structural adjustment programmes, conceived in the gleaming offices of Bretton Woods institutions, have dictated the privatisation of state enterprises, the liberalisation of trade regimes, the removal of subsidies that protected the vulnerable, and the reshaping of entire economic sectors according to neoliberal orthodoxy.

When external creditors determine whether a nation can subsidise fertiliser for its farmers, regulate foreign investment to protect strategic industries, or expand public sector employment to address unemployment, the nation retains sovereignty in name only.

The debt trap functions as neo-colonialism’s most elegant mechanism, a form of bondage that the debtor appears to enter voluntarily. Ghana’s external debt burden — which has periodically exceeded 60% of GDP — creates a perpetual cycle of dependence. Resources that might build universities, hospitals, or renewable energy infrastructure instead flow outward as debt service to foreign bondholders and multilateral institutions.

The cruel arithmetic of compound interest ensures that debts contracted decades ago continue to extract wealth from present generations, a temporal colonisation where the past devours the future. When debt becomes unsustainable, relief comes only with fresh conditionalities, new surrenders of policy autonomy.

The 2002 HIPC initiative, which provided debt relief, simultaneously imposed governance reforms that reshaped Ghanaian institutions according to donor specifications. Freedom from debt purchased through acceptance of external diktat is freedom of a peculiar sort, like a prisoner released on parole who must wear the monitor and observe the curfew.

Trade relationships perpetuate colonial patterns with remarkable fidelity to the past. Ghana remains substantially a primary commodity exporter — cocoa, gold, oil — whilst importing manufactured goods and processed products.

This is the classic colonial division of labour reproduced in post-colonial arrangements: Africa provides raw materials; Europe and Asia add value through processing and manufacturing; Africa repurchases finished goods at prices that embed the costs of this processing plus healthy profit margins.

The cocoa farmer in Ashanti who receives perhaps 6% of the final chocolate bar’s retail value participates in a global value chain structured precisely as it was under colonial rule, where processing, branding, and distribution profits accrue elsewhere.

Economic Partnership Agreements with the European Union, presented as reciprocal free trade, actually lock in these asymmetries by preventing Ghana from protecting infant industries or using tariffs strategically as industrialised nations once did during their own development.

The extractive industries reveal neo-colonialism’s resource dimension with particular clarity. Foreign multinational corporations — AngloGold Ashanti, Newmont, others — extract Ghanaian gold under agreements negotiated when Ghana possessed limited bargaining power. These contracts, often spanning decades, grant concessionary terms, tax holidays, and profit repatriation rights that ensure the majority of mining revenues flow outward.

The environmental degradation remains in Ghana — the mercury-poisoned rivers, the cratered landscapes, the displaced communities — whilst the wealth accumulates in distant shareholders’ portfolios. When a nation cannot control the extraction and distribution of its own mineral wealth, when foreign corporations negotiate terms directly with compliant governments whilst civil society watches helplessly, the independence celebrated in 1957 rings hollow as a drum with no skin.

Yet neo-colonialism’s cultural dimensions cut even deeper than economic exploitation, for they colonise consciousness itself, shaping how Ghanaians perceive themselves and their possibilities. The continued dominance of English as the language of power, governance, and advancement represents linguistic imperialism’s persistence.

To rise in Ghana’s political, economic, or academic hierarchies, one must master the coloniser’s tongue, must think in its grammatical structures, must absorb its conceptual frameworks. Indigenous languages — Akan, Ewe, Ga, Dagbani — become relegated to the domestic sphere, unsuitable for serious discourse, incapable of expressing modernity’s complexities.

This linguistic hierarchy is not natural but constructed, maintained through educational systems that privilege English, through business environments that demand it, and through international institutions that recognise only European languages. When a people cannot conduct their highest affairs in their mother tongues, they suffer a psychic colonisation that material independence cannot undo.

The educational curriculum perpetuates neo-colonial consciousness by teaching Ghanaian children to see the world through European eyes. Students study the French Revolution before Asante resistance wars, Shakespeare before Ama Ata Aidoo, Adam Smith before understanding indigenous economic systems.

The very standards of educational achievement — Cambridge examinations, Western university degrees, internationally recognised certifications — position Europe and America as the arbiters of knowledge and excellence.

This creates what Frantz Fanon termed the colonised mind: Ghanaian élites educated to identify with the West, to measure their nation against Western benchmarks, to see their own cultures as backward or traditional obstacles to progress. When a nation’s educated class looks outward for validation, when “international standards” invariably mean Western standards, when excellence is defined by proximity to European norms, neo-colonialism has achieved its deepest victory.

The World Bank and IMF exemplify neo-colonialism’s institutional architecture — multilateral organisations with formal equality of membership but structural inequality of power. Voting rights in these institutions correlate with financial contributions, ensuring that former colonial powers and the United States maintain decisive influence.

Ghana possesses a nominal voice but cannot meaningfully shape policies that profoundly affect its development trajectory. The prescriptions these institutions impose—fiscal austerity, trade liberalisation, privatisation — reflect ideological preferences of dominant shareholders rather than Ghanaian developmental needs.

That these prescriptions have failed repeatedly—producing decades of anaemic growth, persistent poverty, widening inequality—matters less than that they serve the interests of global capital by opening markets, ensuring debt repayment, and maintaining favourable investment climates for multinational corporations.

Military and security relationships extend neo-colonial dependency into the realm of violence and protection. Ghana hosts AFRICOM exercises, receives American military training and equipment, and participates in security frameworks designed in Washington and Brussels rather than Accra.

Whilst Ghana maintains formal control over its armed forces, the terms of engagement — the equipment supplied, the doctrines taught, the intelligence shared — bind it into security architecture that serves external strategic interests.

When Ghana’s military trains primarily with Western partners, adopts Western military doctrines, and depends on Western equipment and spare parts, its security sovereignty becomes compromised. The nation can deploy its forces, certainly, but the capacity to do so depends on maintaining good relations with external powers that control the supply chains and technical expertise.

Chinese engagement in Ghana presents a contemporary twist on neo-colonial themes, suggesting that neo-colonialism need not bear Western features to function as domination. Chinese infrastructure loans — for roads, ports, hospitals — arrive with their own conditionalities: Chinese contractors, Chinese workers, Chinese materials, debt repayment terms that may include resource concessions or voting alignment in international forums.

The Belt and Road Initiative, whatever its stated intentions, creates dependencies through debt and infrastructure control. When the Port of Tema expansion relies on Chinese financing and expertise, when Chinese companies dominate mining operations, when debt-for-infrastructure swaps mortgage future revenues, Ghana escapes Western neo-colonialism only to risk Eastern variants. The dragon may smile differently than the lion, but both cast shadows that obscure Ghana’s light.

Yet we must resist the analytical trap of denying Ghanaian agency entirely, of reducing Ghana to a helpless victim buffeted by external forces beyond its control. This itself would be a form of intellectual colonisation, reproducing the racist tropes that justified original colonialism by suggesting Africans lack capacity for self-determination.

Ghana has exercised meaningful autonomy in numerous domains: building relatively robust democratic institutions that have survived multiple peaceful transitions of power; cultivating a vibrant civil society that holds government accountable; developing regional leadership within ECOWAS that shapes West African affairs; nurturing cultural industries — music, film, literature — that project Ghanaian creativity across the continent and beyond. These achievements matter, representing zones of genuine sovereignty carved from neo-colonial constraints.

Moreover, Ghana’s leaders bear responsibility for choices that have deepened neo-colonial dependency. Corruption that diverts public resources into private pockets, poor economic management that necessitates IMF intervention, failure to develop industrial capacity or diversify the economy — these reflect domestic failures that cannot be blamed entirely on external forces.

Neo-colonialism provides structural constraints and perverse incentives, certainly, but it does not eliminate choice. To acknowledge neo-colonialism’s reality whilst insisting on Ghanaian agency is to achieve the difficult balance that Senghor himself sought: recognising oppression whilst refusing victimhood, acknowledging external constraints whilst asserting the capacity to transcend them.

The question of whether Ghana suffers from neo-colonialism thus demands a nuanced answer that honours complexity rather than seeking simple certainties. Ghana undeniably operates within neo-colonial structures — economic dependency through debt and unfavourable trade, cultural hegemony through language and education, institutional subordination through international financial architecture, and emerging dependencies through Chinese engagement.

These structures constrain autonomy, extract wealth, and perpetuate underdevelopment in ways that serve external interests. The sovereignty celebrated in 1957 has proven insufficient to escape these mechanisms of control.

Yet Ghana is not merely victim but also actor, not simply dominated but also choosing, not purely constrained but also creating. It navigates neo-colonial structures with varying degrees of success, sometimes resisting effectively, sometimes succumbing to external pressure, sometimes choosing poorly despite having alternatives.

This is the paradox of post-colonial sovereignty: independence achieved but incompletely realised, autonomy claimed but structurally compromised, freedom proclaimed but economically constrained. Ghana suffers from neo-colonialism not as a terminal patient suffers from disease but as a wrestler suffers from a hold — constrained, struggling, still possessing strength, still capable of eventual escape.

The chains we cannot see bind nonetheless, but they are not unbreakable. This is the difficult truth: neo-colonialism is real, powerful, and persistent, but it is not destiny. Recognition of bondage is the first step toward liberation.

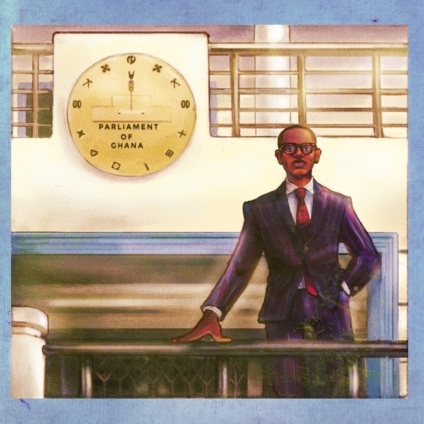

The author, V. L. K. Djokoto (b. 1995) is a forward-thinking Ghanaian cultural theorist, financier and gallerist.

He leads D. K. T. Djokoto & Co — an old-fashioned top-tier multi-family office, established in 1950 — which is deeply anchored on residential real estate; steers the wheels of rural banking across coastal Ghana; revived the Accra Evening News, established in 1948, delicately rebranded into a post-partisan cultural newspaper; and finances a cultic arts and culture department intensely focused on engineering a radiant legacy.

Through expertly crafted artistic experiences, Djokoto seeks to mobilise Ghanaians weaving African music, literature and art.

V. L. K. Djokoto is the author of 'Revolution' and a play, 'Afro Gbede'.

Latest Stories

-

Ho Nurses Training College mounts pressure on UHAS to release its facilities

18 minutes -

140 suspects, 27 dockets – Kwakye Ofosu says ORAL is already delivering results

28 minutes -

Cabinet approves special tribunals to tackle corruption and illicit wealth cases

48 minutes -

Ghana Immigration Service rescues 73 from abuse in an anti-fraud operation

1 hour -

EOCO freezes ¢1.5bn in assets linked to corruption investigations – Kwakye Ofosu

1 hour -

Wildlife to replace historical characters on British banknotes

2 hours -

China and North Korea to resume passenger train service after 6-year halt

2 hours -

Meghan to headline ‘girls’ weekend’ in Australia for 300 women

2 hours -

ORAL: We won’t manipulate judiciary for political ends – Gov’t spokesperson

2 hours -

Congo Republic’s Sassou set to extend long rule, focus on succession

5 hours -

At least six dead in Switzerland bus fire

5 hours -

GH¢50m frozen in Wontumi’s accounts – Gov’t spokesperson Felix Kwakye Ofosu reveals

5 hours -

Brent to trade above $95 for next two months on Iran war, EIA says

6 hours -

US nears deal to resume intelligence operations in Mali

6 hours -

Al Qaeda-linked group killed at least 12 truck drivers in Mali, HRW says

6 hours