Audio By Carbonatix

Ghana’s electoral system has long been praised for its stability and regularity. Yet new research suggests that beneath the surface of competitive elections lies a political economy that systematically restricts access to power, particularly for women, youth and first-time aspirants.

A study by the Gender Centre for Empowering Development (GENCED), examining internal party primaries and the 2024 general elections, points to a convergence of financial demands, entrenched patronage networks, and cultural attitudes that favour wealthy and well-connected candidates over less-resourced but qualified contenders.

At the centre of the findings is the cost of political participation. Filing fees for party primaries have risen sharply, effectively transforming nomination contests into high-stakes financial races.

During the 2024 primaries, parliamentary aspirants in the New Patriotic Party paid GHS 80,000, while presidential hopefuls paid GHS 350,000. In the National Democratic Congress, parliamentary hopefuls paid GHS 40,000, with presidential aspirants paying as much as GHS 500,000.

GENCED’s analysis indicates that these fees, when combined with campaign costs and inducements for delegates, create barriers that disproportionately exclude women, youth, and newcomers to politics. For aspirants without access to substantial personal wealth or financial backers, the study notes, the cost of entry alone is often prohibitive.

Beyond formal fees, the report highlights the decisive role of influential party figures, commonly referred to as “godfathers.”

These actors, the study argues, wield outsized influence in determining who secures nominations, often prioritising loyalty, networks and financial capacity over competence or grassroots support. In such an environment, internal party democracy becomes constrained, with outcomes shaped well before ballots are cast.

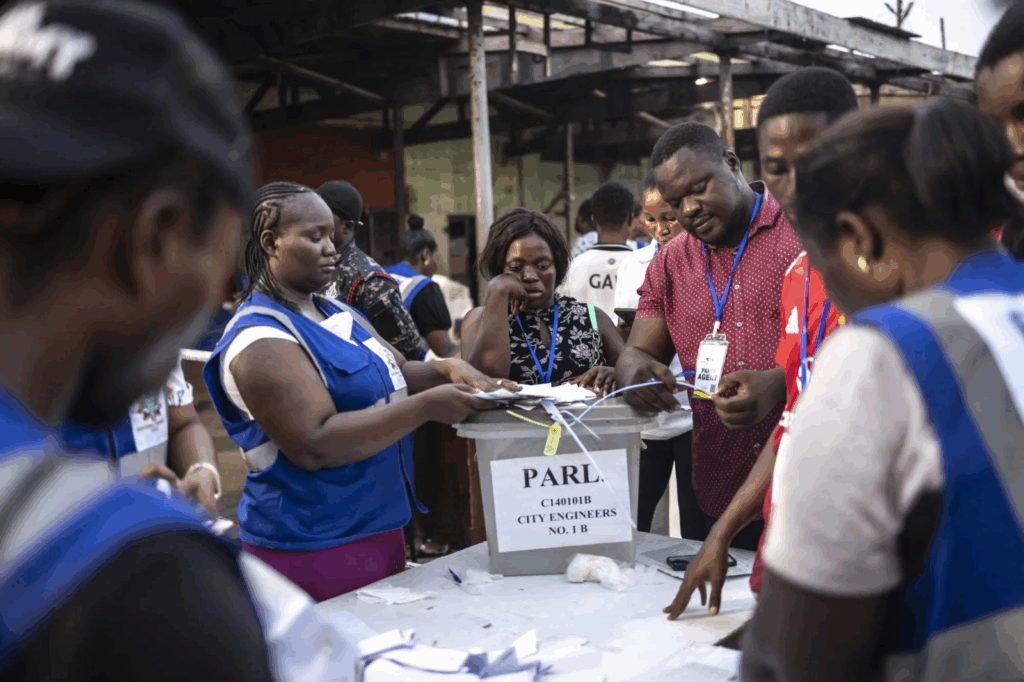

These dynamics persist despite Ghana’s long record of electoral continuity. Since the return to constitutional rule in 1992, the country has held eight general elections prior to the 2024 polls, with power alternating between the NPP and NDC. In the most recent elections, John Mahama returned to the presidency with about 56 percent of the vote, while the NDC secured 183 of the 276 parliamentary seats.

GENCED’s findings suggest, however, that electoral competitiveness at the national level has not translated into equitable access to political office. Instead, the study concludes that money and political patronage continue to outweigh merit in shaping who appears on the ballot in the first place.

Some corrective measures exist. Certain political parties offer fee waivers for women aspirants, while civil society organisations, including CDD-Ghana, provide mentorship and leadership programs for young people.

The report argues, however, that these interventions remain limited in scope and impact without stronger enforcement mechanisms within party structures.

The passage of the Affirmative Action (Gender Equity) Act, 2024 (Act 1121), is identified as a potentially significant development. The law provides a framework for improving representation, setting a minimum threshold of 30 per cent women in public office, rising to parity by 2034. GENCED cautions that without rigorous implementation and monitoring, the legislation risks falling short of its objectives.

Concerns about the broader implications of money-driven politics are echoed by policy experts. Dr Michael Akagbor, Programs Manager for Human Rights and Social Inclusion at CDD-Ghana, warns that the dominance of financial power and patronage networks risks eroding merit, discouraging capable aspirants and weakening public confidence in electoral outcomes.

The Electoral Commission, for its part, acknowledges the challenges but maintains that its mandate is limited. According to the EC’s Director for Gender, Youth, and Persons with Disabilities, Abigail Amponsah, the Commission is responsible for administering elections and enforcing electoral laws, not regulating internal party processes. Any expansion of its authority, she notes, would require constitutional reform.

The study underscores that while Ghana’s democracy has matured institutionally since 1992, systemic barriers within party politics continue to marginalise minorities, particularly women and youth. Without deliberate reforms to dismantle financial, political, and cultural obstacles, the report warns that Ghana risks entrenching an exclusionary political system that undermines democratic legitimacy and representation.

Latest Stories

-

Fake vice presidential staffer remanded over visa fraud

4 hours -

Mobile money vendor in court for stealing

4 hours -

Eleven remanded over land guard case activities

4 hours -

Air Force One set for makeover paint job with new colours

4 hours -

Bodo/Glimt stun Inter Milan to continue fairytale

4 hours -

Ga Mantse stable after early morning accident

4 hours -

Pressure mounts as Arsenal blow 2-goal lead to draw at Wolves

5 hours -

Club Brugge fight back to leave Atletico tie delicately poised

5 hours -

Benfica claim ‘defamation campaign’ against Prestianni

5 hours -

Sinner and Alcaraz reach Qatar quarter-finals

5 hours -

Kenpong Travel and Tours to launch 2026 World Cup travel package on Friday

5 hours -

‘It hurts a lot’ – Coutinho announces Vasco exit

5 hours -

Provider – A new gospel anthem of faith, hope, and divine supply

5 hours -

MOBA heads to Accra Ridge for 11th National Conference on Feb 21

5 hours -

Ghana’s Doris Quainoo clocks new PB 8.23s to claim second place at Jarvis City Invite

6 hours