Audio By Carbonatix

Ghana’s petroleum downstream sector has rarely attracted as much public attention as it has in recent weeks.

The decision by Star Oil to suspend its membership of the Chamber of Oil Marketing Companies (COMAC) has turned what might otherwise have been a technical regulatory disagreement into a national conversation about competition, consumer welfare, and the meaning of deregulation.

At the centre of the dispute lies one policy instrument: the fuel price floor.

This is not merely a disagreement between an oil marketing company and an industry body. It is a deeper policy question about how Ghana manages liberalised markets in politically sensitive sectors and whether well-intentioned safeguards are quietly re-introducing the very distortions deregulation was meant to eliminate.

Ghana formally deregulated petroleum pump prices in 2015, ending years of administered prices and subsidy arrears that had burdened the national budget and undermined supply reliability. The logic was straightforward: allow prices to reflect market realities international product prices, exchange rate movements, taxes, and distribution costs while competition disciplines margins.

For nearly a decade, that framework broadly held.

However, concerns gradually emerged within the industry that aggressive price undercutting by some players particularly in periods of FX volatility was leading to below-cost pricing, threatening smaller or less-capitalised operators and potentially destabilising supply.

In response, the National Petroleum Authority (NPA), following multi-stakeholder consultations, introduced amended pricing guidelines in 2024, empowering it to publish minimum pump price floors for deregulated petroleum products within each pricing window.

The NPA’s justification focussed on a narrow and technical foundation: the floor would reflect statutory taxes, levies, and fixed distribution costs, while leaving marketers’ margins free to compete above that baseline. In theory, competition would remain alive just not destructive.

In practice, the controversy now suggests that theory and reality may be diverging.

Star Oil’s withdrawal from COMAC is best understood as an act of structural discomfort.

The company’s central argument is that the price floor impedes downward price transmission. When global prices soften or the cedi strengthens, pump prices do not adjust as quickly or as visibly as consumers expect. In effect, the floor can act as a price anchor, muting the benefits of favourable market movements.

From a competition standpoint, this raises an uncomfortable question:

Can a mechanism designed to prevent under-pricing end up protecting prices themselves?

COMAC, for its part, has defended the floor as a necessary stabiliser, denying any intent to silence dissent and framing the policy as a shield against market abuse. That defence is not frivolous. No jurisdiction tolerates predatory pricing aimed at eliminating competitors.

But perception matters. When the largest contributor to an industry body feels its views are not fairly represented, governance credibility becomes part of the policy problem.

In public discourse, opposition to the price floor often morphs into calls for a price ceiling a maximum pump price that ensures consumers benefit immediately from favourable movements in FX or international markets.

Politically, this is powerful. In an inflation-sensitive economy, a ceiling signals action and compassion.

Technically, however, it is fraught.

A price ceiling that is not cost-reflective simply recreates old problems in new packaging: supply rationing, selective station closures, quality compromises, smuggling incentives, and inevitably hidden subsidies and arrears. Ghana has lived through that cycle before, and deregulation was the hard-won escape route.

The choice, therefore, is not between a floor and a ceiling. It is between smart regulation and blunt intervention.

Four broader issues now demand attention:

First, Ghana has not yet produced sufficient public data to justify the floor’s continuation. If destructive undercutting was the problem, regulators should show evidence pre- and post-floor pricing behaviour, margin compression, supply disruptions, and competition metrics.

Second, deregulation cannot mean “market prices when convenient, intervention when uncomfortable.” A permanent price floor risks blurring that line.

Third, industry bodies like COMAC must demonstrate that they represent diverse commercial models, not only consensus positions. Dissent is not disloyalty; it is policy oxygen.

Fourth, consumer trust depends less on price controls and more on price transparency.

There is a more credible path forward.

Rather than hard floors or ceilings, Ghana should strengthen price-build-up transparency, publishing simplified reference ranges for each pricing window: FOB prices, FX assumptions, tax components, and distribution margins so consumers understand what they are paying for.

At the same time, regulators should enforce targeted anti-predatory pricing rules, punishing deliberate below-cost selling intended to eliminate competition, without penalising legitimate efficiency or scale advantages.

Where exceptional volatility arises, a temporary price corridor, triggered by clearly defined thresholds and sunset clauses, is preferable to permanent price intervention.

And if the government seeks consumer relief, it should do so honestly through tax or levy adjustments, not by embedding fiscal policy inside pricing mechanics.

Star Oil’s exit from COMAC is not the crisis. It is the warning light.

The real question is whether Ghana’s petroleum pricing framework is quietly drifting from deregulation toward managed prices by another name. Stability matters. So does competition. And so does consumer welfare.

Good regulation does not choose one at the expense of the others. It balances them transparently, lawfully, and with evidence.

That balance is now overdue for review. It’s time for the NPA to engage all stakeholders.

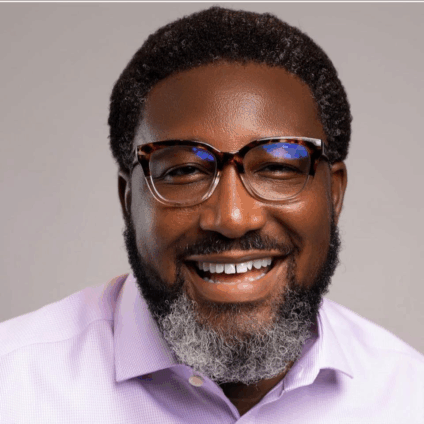

Lom Nuku Ahlijah is a Ghanaian lawyer, academic, and energy sector expert with deep experience in commercial law, regulatory governance, and public administration. He is a Lecturer and Immediate Past Head of Department at the GIMPA Law School, serves as Acting Legal and Compliance Officer at GIMPA, and is a member of the Council for Law Reporting, contributing to the development of Ghana’s authoritative law reports. He is Managing Attorney of Integri Solicitors & Advocates and a former Senior Legal Counsel at GRIDCo, where he worked on major national and regional power projects. A dual-qualified lawyer admitted in Ghana and New York, he holds an LL.M. from Harvard Law School and is the author of leading books on Commercial Law and Ghana’s Electricity Law and Policy.

Latest Stories

-

Kingsford Boakye-Yiadom nets first league goal for Everton U21 in Premier League 2

21 minutes -

We Condemn Publicly. We Download Privately — A Ghanaian Digital Dilemma

2 hours -

Renaming KIA to Accra International Airport key to reviving national airline – Transport Minister

3 hours -

Interior Minister urges public not to share images of Burkina Faso attack victims

3 hours -

Unknown persons desecrate graves at Asante Mampong cemetery

3 hours -

I will tour cocoa-growing areas to explain new price – Eric Opoku

3 hours -

Ghana to host high-level national consultative on use of explosive weapons in populated areas

3 hours -

Daily Insight for CEOs: Leadership Communication and Alignment

4 hours -

Ace Ankomah writes: Let’s coffee our cocoa: My Sunday morning musings

4 hours -

Real income of cocoa farmers has improved – Agriculture Minister

4 hours -

I’ll tour cocoa-growing areas to explain new price – Eric Opoku

4 hours -

Titao attack should be wake-up call for Ghana’s security architecture – Samuel Jinapor

4 hours -

New Juaben South MP Okyere Baafi condemns Burkina Faso attack, demands probe into government response

4 hours -

A/R: Unknown assailants desecrate graves at Asante Mampong cemetery

4 hours -

What is wrong with us: Africans know mining, but do not understand the business and consequences of mining

5 hours