Audio By Carbonatix

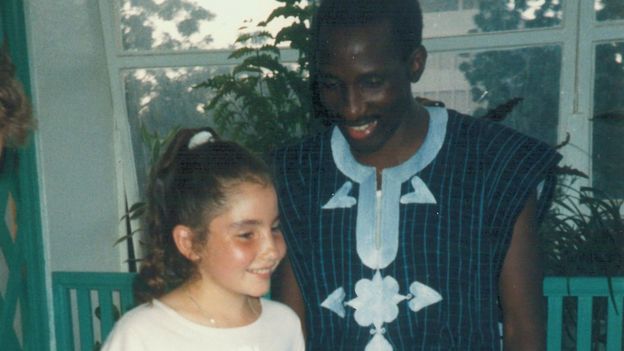

One picture brings it all back home to me again: Me, an 11-year-old London school pupil, gazing up smiling into the eyes of Thomas Sankara, then president of Burkina Faso.

The picture is too dark; it isn't particularly well composed - the sound engineer is in the way, getting my fellow interviewer, 14-year-old Dan Meigh, ready to film our encounter.

But it's the kindly warmth in Capt Sankara's eyes as he looks back at me that takes me back; the sense of calm composure, of someone at ease with himself, and at ease with his young, potentially unpredictable young interlocutors.

It's the simple furniture, the lack of opulence, the lack of Western power-dressing in favour of African fabrics and bare arms.

Little did we realise at the time that we would become the last non-Africans to interview the Burkina Faso leader.

On 15 October 1987, he was assassinated in a coup led by his erstwhile brother-in-arms and best friend Blaise Campaoré - who went on to lead the country for the next 27 years.

We had been in Burkina Faso as winners of a competition run by the BBC news programme for children, Newsround - sent to look at projects run by Sport Aid, a famine-relief fundraising campaign.

The interview took place in the spartan presidential palace

Hearing the news of Capt Sankara's death back home in London, as editing of our programme was still under way, I was saddened and shocked, but the shock was soon superseded by the interview requests that came flooding in from prime-time chat shows, where I was jokily quizzed about bagging a "scoop" at such a young age.

It was only as I grew older that I began to appreciate the legendary status of the man I had interviewed - despite some criticism of his rule, his admirers remain numerous and ardent - and of the symbolism of his murder in the political context of post-colonial Africa.

Thomas Sankara - 'Africa's Che Guevara'

For Capt Sankara was pursuing a political project described as revolutionary in scope. And unlike many other African icons, such as South Africa's Steve Biko, he did - at least for a time - have the power to begin trying to make his vision a reality.

Tree planting

I witnessed some of it for myself when I was there.

As I have said, he did away with the ornaments enjoyed by many leaders.

We saw few guards at the presidential residence, something Capt Sankara may have come to regret.

Outside there were no luxury cars - we heard he had given them to the national lottery as prizes, replacing the fleet with cheap Renaults.

One of Capt Sankara's priorities was fighting the desertification of his country.

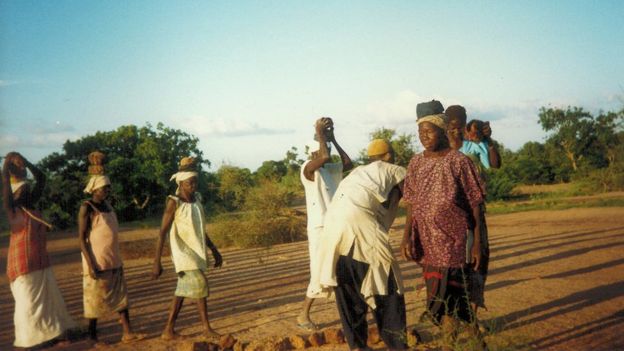

People built "diguettes" to fight desertification and improve crop yield

He told us he wanted to make it a commonplace that everyone should plant a tree on their birthday - we planted our own.

He had sent 200,000 people to plant trees and cordon off land, preventing nomadic animals from stripping the land of vegetation.

We saw home-grown solutions being implemented to problems of malnutrition and poverty - for instance, people building "diguettes", stone walls which stop fertile topsoil running off arid agricultural land when it rains, permitting more abundant crops to be grown.

Statistics suggest that the policies Capt Sankara implemented during his short four years in office yielded some startling results.

Many more children went to school under Thomas Sankara's rule

School attendance went from 6% to 22%, millions of children were vaccinated and 10 million trees were planted. The number of women in government soared, female genital mutilation was banned, and contraception was promoted.

Like me, Lamine Konkobo, a Burkinabé journalist with BBC Afrique, was only a child when Capt Sankara was killed - and, like me, he only came to fully understand his political importance as he grew up.

"I was growing up in a village where Sankara was seen as a challenging figure in terms of the ideas he promoted, in terms of women's independence and empowerment, for instance," he told me.

"That did not sit well in the countryside."

Exercise made compulsory

Capt Sankara had challenged the old centres of power in Burkina Faso: Traditional leaders and big business.

So among them there was a sense of relief when his rule was over, a relief shared by Lamine's father.

Most young people supported Capt Sankara, but misgivings about his rule even extended to progressive figures, including some intellectuals, who felt his quest to develop the country had an overly paternalistic, authoritarian edge.

President Sankara made physical exercise mandatory, for example, so he could harness the powers of the population for his projects and do it without relying on external aid.

Workers accused of not pulling their weight were sometimes tried in "revolutionary tribunals", which were supposed to target corruption.

But the perceptions of Capt Sankara changed after Mr Campaoré came to power.

Under President Campaoré's programme of "rectification", power was restored to traditional leaders and businessmen.

"Justice for Sankara" became a rallying cry decades after his demise

Opponents were assassinated and a market economy was implemented that many blamed for impoverishing the majority and enriching a tiny elite, including Mr Campaoré and his own family.

These changes brought about a reappraisal of Capt Sankara's achievements among many - including Lamine's father.

"After [Sankara] died, we discussed his integrity, his public service, and my dad said everyone had been defending their own interests and had not been not open enough to hear him. 'Now I understand he was much better than what we have now,' my dad said. He died a repentant man."

Although Mr Campaoré, who was overthrown in 2014, erased Capt Sankara's project, ultimately he failed in his aim to erase his vision, Lamine believes.

"This is the real legacy of Thomas Sankara. The ideas he tried to promote remain despite all the efforts of Blaise Campaoré to get people to forget.

"Ultimately those ideas were what spurred people to rise up in 2014 against Blaise Campaoré: They confronted armed police officers and soldiers and they made their point.

"The uprising would not have been possible without young people being driven by this powerful belief within them - the belief that they were pursuing a vindication, that the regime that killed their hopes would go."

Latest Stories

-

How Nico Cantor became one of the top voices in American soccer

17 minutes -

Ghana colorectal cancer patients face low survival rates, KNUST study finds

28 minutes -

Police arrest suspect in GH₵ 7.5m daylight robbery at Adabraka

30 minutes -

Armwrestling: The Golden Arms’ 2025 Triumph and an Era of Unprecedented Victories

32 minutes -

Ghanaian researcher wins ASCE editors’ recognition for modular construction study

33 minutes -

Corruption fight: I don’t think there’s political persecution or witch-hunting – Edem Senanu

43 minutes -

Police deploys personnel to heighten security ahead of watchnight services

1 hour -

Education in Review: 2025 marks turning point as President Mahama resets Ghana’s education sector

1 hour -

The Cedi ressurection: Goldbod didn’t promote Galamsey to strengthen It

1 hour -

The Diplomatic Surgeon: How Ablakwa’s institutional reset is anchoring the Mahama legacy

1 hour -

Professor Agyeman-Duah labels CJ Torkonoo’s removal a key low point in Mahama’s administration

2 hours -

CDM calls on President Mahama to act over ‘alarming’ GoldBod trading losses

2 hours -

CDM rejects claims that BoG losses were due to Gold Purchase Programme

2 hours -

Ghanaians experiencing tangible relief under Mahama administration – Professor Baffour Agyeman-Duah

2 hours -

Livestream: 2025 Year in Review on The Pulse

3 hours