The advent of the novel coronavirus in Ghana exposed a lot of weaknesses in our society – weaknesses we had often overlooked and thought to be normal.

Such weaknesses include a poor health care system, a stagnated educational system, and the lack of much-needed internet facilities to enable workers and students to continue with their schedules seamlessly from home, among other things.

But an aspect of our society that has always been overlooked and might continue to be overlooked post-Covid-19 is our building system. How we design (architecture) and build our homes, cities, health care facilities, schools among many others.

Indeed one might ask, ‘what has Covid-19 got to do with how we build and plan our cities?’ The truth is, it does! Pandemics and epidemics similar to the novel coronavirus have shaped the way we build and design buildings and cities from the very first pandemic, the bubonic plague.

The first bubonic plague which occurred in the 14th century led to the surfacing of the Gothic style of buildings which we now see in the design of cathedrals - a heightened expression of emotion and an emphasis on individual differences as a result of the devastation its architects witnessed.

It was cholera that influenced much of the Western world’s modern street grid, as 19th-century epidemics prompted the introduction of sewage systems that required the roads above them to be wider and straighter, along with new zoning laws to prevent overcrowding.

The third plague pandemic, a bubonic outbreak that began in China in 1855, changed the design of everything from drainpipes to door thresholds and building foundations, in the global war against the rat.

And the wipe-clean aesthetic of modernism was partly a result of tuberculosis, with light-flooded sanatoriums inspiring an era of white-painted rooms, hygienic tiled bathrooms and the ubiquitous mid-century recliner chair.

It is therefore not farfetched with the advent of Covid-19, and the protocols set in place to mitigate its spread, to start considering what exactly might change in the way cities are planned and how buildings would be put up in the years to come as a measure against future outbreaks.

Will our sidewalks widen to ensure social distancing? Will our cities be sub-divided into self dependent urban clusters to mitigate the spread of future viruses? Or will our cities be made less dense to control overcrowding?

One thing is for sure, the future is uncertain.

Kwabena Adofo Kukah, a chartered architect with Arttekrafte Practice LLC says the concept of social distancing or physical distancing will pose a challenge for the design of public spaces where very often than not, people find themselves congregated closely to each other; like markets, bus terminals and places of worship among others.

“It may be slightly premature to put a design, architecturally, on how public spaces especially, will look like considering we are still weathering the storm,” he said.

According to Kukah despite the uncertainty associated with the emergence of the virus, some educated guesses can be made as to how the future could look like.

“The first has to do with office spaces. There has been a great affinity for virtual office spaces where most people have had to work from home, thanks largely to technology. This gives rise to the theory that depending on how this works for most organizations, there may be the need to cut back on huge rent and exist largely in the virtual space.

“If this is popular, then expect a lot of empty office rental spaces in the city centres which may want to adapt to alternative uses,” he said.

He added that “there is also a whimper for offices to consider going back to the partitioned days, abandoning the open-plan concepts which seem to have caught on in Ghana in the past few years.”

The open plan office which came to replace the cubicle office was a means of showcasing, at least symbolically, the democratic and egalitarian ethos of a company’s culture. The German term ‘Bürolandschaft’ describes the concept of a company’s leaders being ‘just one of the gang’, sat amongst their employees and sharing information, resources and experience.

But proximity no longer seems tempting in this coronavirus era.

He, however, stresses the need to reduce contact with surfaces as much as possible. “Another certainty in the design space will be a drift towards automation.”

With 80% of infectious diseases transmitted by touching contaminated surfaces, automation might just be the right way to go.

“More doors will open on their own, there will be no need to neither touch the taps nor flush the toilet in a public washroom, etc. Since scientists and virologists say that the virus can live on certain surfaces for a certain period of time, a major design change will involve the automation of a lot of areas in buildings, largely eliminating the need for human touch.”

Proper ventilation over the years has been key in mitigating the spread of diseases, from tuberculosis to the Spanish flu. To this end, Kukah believes, “Climate control in buildings will see significant improvement as there will be the need to continually introduce fresh air into enclosed spaces that houses a large number of people; or even periodically disinfect such spaces.”

He adds that “building materials, fabrics and finishes used in construction may see significant improvement in their anti-bacterial or anti-fungal properties. These are usually products of research thus if research institutions are minded to, they can develop such elements that house such properties that viruses cannot dwell on them.”

The bigger picture with the post-Covid-19 Ghanaian architectural landscape will be the major changes enforced by government in preparedness towards a similar crisis in the near future. Let’s call a spade a spade; this won’t be the last pandemic to hit the world.

According to the World Economic Forum, “with increasing trade, travel, population density, human displacement, migration and deforestation, however, as well as climate change, a new era in the risk of epidemics has begun. The number and diversity of epidemic events has been increasing over the past 30 years, a trend that is expected to intensify.”

This therefore calls for structural changes in our urban planning.

As is noted by Kuukuwa Manful, a PhD candidate at the SOAS University of London and an architect, whatever changes that may occur post-Covid-19 will depend on the action or inaction of those at the helm of power in response to the challenges that have risen in this Covid-19 era.

“None of us can accurately predict the future, but those of us who study histories and attempt to make sense of the socio-political factors, contexts and outcomes can attempt guesses.

“That said looking at some of the histories of pandemics around the world and in Ghana in particular I can say with certainty that if we continue to do things the same way, the future of formalised state-driven architecture and urbanism is likely to be influenced by the same inequalities,” she said.

Manful who is interested in African architectural history and social architecture reckons that the challenges we are facing as a country in the architectural sense is as a result of inequitable urban planning, at the expense of the poor.

“Let’s look at some of Accra’s history for example, ostensibly in response to fears of the bubonic plague and other diseases, the colonial government in Accra pushed for more segregation in the residential areas.

“Black people in Accra were excluded more and more from the areas grabbed by the white residents. Even though these diseases mostly came to Accra through European travellers, it was the natives that were viewed by the colonial governments as unclean and this was reflected in urban planning and architecture policies.

“Instead of making the city work for everyone, it was made to work for the most powerful in the society,” she said.

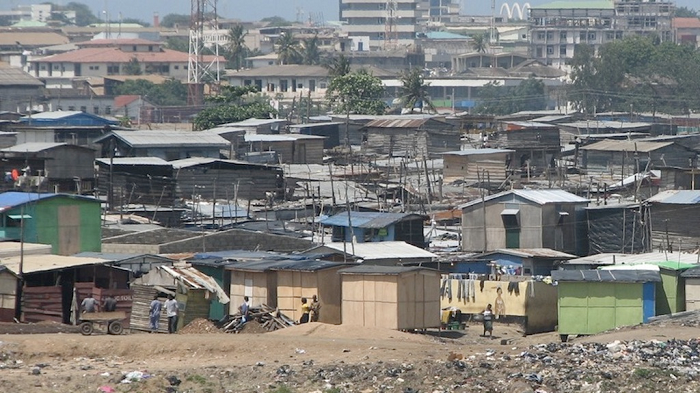

Unfortunately such inequitable urban planning have created the mass slums where social distancing cannot be practiced, they have led to the poor drainage systems our cities, especially Accra is saddled with; leading to frequent flooding and cholera outbreaks, the extreme traffic which are a major air pollutant in our urban areas, insecurity, congestion and dysfunction.

“And yet Ghanaian planners, academics and other technocrats have been creating really good plans, regulations and policies through the years. Unfortunately, due largely to political will, these plans are rarely taken seriously by those with power and in some of the cases where there is some attempt to implement, it's not even done well,” Manful noted.

But where are the enforcers and what are they doing? In an opinion piece on Ghanaweb titlted “Do we really have zoning laws in Ghana?” Peter Atsu Tsikata, a real estate consultant laments, “do we really have zoning regulations in Ghana? And if we do, do we really enforce them?”

Architect Kukah in this interview answered saying, “in my view, Ghana has not been bereft of solid zoning laws. The laws tell you where you can site your house, light industry or even recreational space. Our bane has been and will be enforcement.

“It is unclear whether the enforcers are unsure how to enforce or they feel overwhelmed by the problems that have arisen as a result of long years of neglect. This present situation presents a fine opportunity to revisit zoning in certain aspects of the city life and ensure strict adherence to the regulations.

He continued, "it should be possible to re-engineer markets without placing a single block on the land such that sanitation and a certain sense of order are reintroduced into the public space.”

He suggests, that per the difficulties the country is facing now in restricting smaller communities during the lockdown, “there may be the need to re-plan settlements such that they are self-sufficient in ways that it would be easy to close down smaller units within the city where infections may be prevalent, such that people do not have to travel too far out of those zones to purchase basic supplies in bulk.”

In conclusion, though there may not be any immediate and drastic change in urban planning post-covid-19, our preparedness towards the next pandemic or epidemic will most likely depend on the actions or inactions of our leaders after this pandemic.

In the words of architect Manful, “post-Covid-19 architectural design will most likely look like the policies or even the lack of planning and policies that follow the pandemic. The possibilities of what it could be are limitless, but we must actively work towards building the future that we want and need.”

Cornerlis Kweku Affre is a level 300 student of the Ghana Institute of Journalism and currently an intern at Myjoyonline.

Latest Stories

-

Dr. Ayensu-Danquah defends professorship, stating 15 years of teaching surgery

45 minutes -

Access Bank honoured with two prestigious awards at 2025 HESS Awards

1 hour -

Oti Region to get university within my tenure – Mahama reaffirms pledge

1 hour -

Daughter killed in father’s arson attack over sex denial

3 hours -

NPA Scandal: Four suspects remain in custody after failing to meet bail conditions

4 hours -

NPP to open 2028 flagbearer nominations on July 29

4 hours -

Sam George to open Pan-African AI Summit 2025

5 hours -

NDC opens nominations for Akwatia parliamentary primaries on July 28

5 hours -

Guinness Ghana DJ Awards opened new doors for my career – DJ Pho

6 hours -

Mohammed Sukparu commits to advancing Ghana’s Artificial Intelligence agenda

6 hours -

‘What is coding?’ – Question raises eyebrows during Deputy Communication Minister-nominee’s hearing

6 hours -

WAFCON 2024: Ghana’s Black Queens claim third-place after penalty win over South Africa

6 hours -

Ghana celebrates 100-year-old WWII veteran Joseph Ashitey Hammond

7 hours -

Measures announced in Mid-Year Budget Review fully in line with programme objectives – IMF

7 hours -

This Saturday on Newsfile: AG drops charges in uniBank trial, Aud-General’s report, and Mid-Year Budget Review

7 hours