Audio By Carbonatix

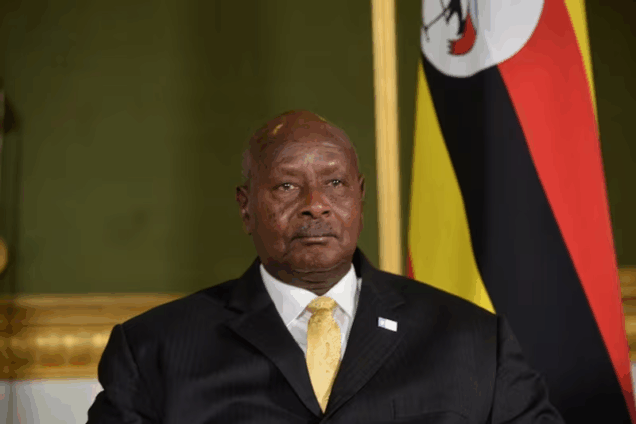

When President Yoweri Museveni first emerged on the African stage in the 1980s, Western capitals and many on the continent hailed him as part of a new breed of leaders.

Like Paul Kagame in Rwanda, Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia, and Isaias Afwerki in Eritrea, Museveni was a soldier who had fought to dislodge chaotic, violent regimes and who spoke the language of liberation, reconstruction, and stability.

He carried with him the aura of a man who had fought for national rebirth. In fact, the regime that he had fought for close to five years had nicknamed him a bandit and likened him to the former English legendary outlaw Robin Hood, who stole from the rich to reward the poor.

That image, carefully cultivated in interviews, books, and public appearances, rested on real credentials. Museveni cut his teeth in the liberation politics of East Africa. As a student at the University of Dar es Salaam in the 1960s, he moved in circles with the then Tanzanian President, Julius Nyerere, and other pan-Africans. Tanzania at the time was a sanctuary for liberation movements from across the continent. He trained alongside Frente de Liberacao de Mocambique (Frelimo) fighters in Mozambique, organised exile groups in Tanzania, and wrote about the continent’s ailments, among them the corrosive tendency of leaders to overstay their welcome. In his autobiography, Sowing the Mustard Seed: The Struggle for Freedom and Democracy in Uganda, and public speeches, he framed himself as a break with the past: not “mere a change of guards but a fundamental change.”

And yet, four decades after he strode into Kampala’s parliament building in 1986, promising a new order, Uganda is a different country from the one many expected. The trajectory that once seemed plausible: liberation to liberal rule to accountable government, has been interrupted and, in many respects, inverted. The man who once warned against “overstaying in power” has presided over favourable constitutional amendments, political manoeuvres, and a security posture that have consolidated his hold on the state and curtailed fundamental freedoms. The question now confronting observers at home and abroad is a blunt one: how did the liberator become the entrenched strongman?

A revolution born of war

Museveni’s route to power was forged in violence and exile, a context that helps explain both his initial credibility and some of the traits that followed. In the early 1970s, he assembled and trained guerrilla forces, repeatedly testing the boundaries of regional politics. His early incursions against Idi Amin’s Uganda were costly and chaotic: poorly supplied and sometimes disastrously executed, they left trails of reprisals and civilian suffering. Even then, regional diplomacy and Nyerere’s backing created space for exile fighters to regroup and rearm.

When Amin’s rule collapsed in 1979, the patchwork of exile organisations, including Museveni’s Front for National Salvation (FRONASA), was folded into the broader Uganda National Liberation Army. Museveni served briefly as a minister of defence in the post‑Amin administration, but it was his later guerrilla outfit, the National Resistance Army (NRA) and its campaigns in the early 1980s that established the credentials that many romanticised: a victorious rebel movement that marched on Kampala and declared a new political beginning in 1986.

Promises and the politics of permanence

Museveni’s rhetoric in those early years, invoking Nyerere, pan‑African solidarity, and a moral obligation to rebuild, resonated powerfully. He criticised the very habit of prolonged personal rule that he had later practised. His book, “What is Africa’s Problem (Speeches and Writings on Africa),” and speeches spoke of democratic renewal and the dangers of entrenched leadership. Yet, over the course of his presidency, the formal institutions and norms that protect political competition and civil liberty have been steadily weakened.

The mechanisms of that transformation are both legal and coercive. The much-cherished 1995 Constitution and the presidential five-year term limits were amended. Opposition politicians have faced detention; rivals have been sidelined, intimidated, or disappeared. Press freedom and civic space have been eroded by laws, harassment, and a security apparatus that increasingly interprets dissent as a security threat. In private conversations recounted by former allies, and sometimes in public remarks that initially sounded ambiguous, Museveni signalled an intolerance of contestation: the idea that alternatives would be hard to find, and that politics ought to be managed rather than allowed to run free.

There are multiple dynamics at work. One is the logic of revolutionary movements turned states: leaders who fought for liberation often come to see the revolutionary project as indivisible from their personal leadership. Another is the role of patronage and security networks. Family members and loyalists, most visibly his brother, long‑time military figure General Caleb Akanwanaho, who is largely known by his nom de guerre Salim Saleh, occupy positions that help anchor the regime. Over decades in which survival felt precarious, and with multiple domestic and regional threats, a politics of consolidation became rationalised as necessary for stability.

But rationales of stability can be self‑reinforcing. As institutions weaken and opposition is squeezed, the space to refresh leadership, to hold rulers to account, or to introduce new ideas dwindles. Promises about preventing “overstaying” calcify into a defence of continued rule. What was at first framed as a revolution for the people risks becoming a revolution for the leadership.

The costs for Uganda

For ordinary Ugandans, the consequences are tangible. Curtailment of free expression and the press makes it harder to expose corruption, to mobilise social demands, or to contest flawed policies. Opposition leaders, when permitted to campaign at all, do so under the shadow of legal restrictions and security harassment. Civil society finds its manoeuvring room narrowed. International partners that once celebrated Museveni’s stability are now forced into awkward calculations: whether to prioritise security and cooperation or to insist on rights and democratic principles.

Museveni’s story is not unique. Across Africa and beyond, the arc from guerrilla leader to long‑serving president has been repeated: what began as liberation can harden into a monopoly. But that does not make it inevitable. The evolution depends on choices, choices to defend institutions, to tolerate dissent, and to allow leadership to be renewed peacefully.

A question of legacy

Museveni’s record is mixed. Under his rule, Uganda has seen periods of relative order, infrastructure projects, and a foreign policy that kept the country engaged in regional affairs. Yet those accomplishments sit alongside an expanding executive, shrinking civic freedoms, and a political culture that makes succession and renewal fraught.

For a man who once sounded the alarm about leaders who cling to power, the final judgement will be measured by how his tenure is remembered: as a liberation that delivered genuine institutions and opportunities for successive generations, or as a revolution that became so entwined with one ruler’s hold on the state that it precluded the very pluralism he once championed.

The man who once penned critiques of life presidents, who spoke of "fundamental change," has become the very archetype he condemned. The principles articulated to Nyerere and in his early writings— accountability, democratic transition, service to the people— appear abandoned. Instead, Museveni presides over a system marked by patronage, militarised politics, and the suppression of dissent. The "fundamental change" promised in 1986 now looks, in hindsight, like the foundation for a dynastic project built on permanence.

Uganda’s tragedy is not merely one of a leader grown old in office, but of a revolutionary ideal profoundly betrayed. Museveni’s journey from liberator to long-reigning autocrat stands as a stark lesson in how the mantle of revolution can cloak an enduring hunger for power, leaving the aspirations of a nation and the principles once held sacred as casualties along the way. The question haunting Uganda now is not about Museveni's past victories, but about the legacy of a liberation that ultimately imprisoned its own people.

Ugandans, and observers across Africa, are left to weigh the bittersweet irony. The shepherd who promised to lead his people out of chaos presided, over time, over a consolidation of power so thorough that it has left many asking whether the liberation was for the many or for the few. The contest over that legacy is not finished.

Latest Stories

-

Ivory Coast considers reforming cocoa marketing system to tackle excess supply, sources say

1 hour -

‘Not appropriate’ for Iran to be at World Cup – Trump

1 hour -

US eases Russia oil sanctions as Iran war pushes up energy prices

2 hours -

China passes new ethnic minority law, prioritises use of Mandarin language

2 hours -

Nepal ex-rapper’s party wins election in landslide after Gen Z protests

2 hours -

Qantas agrees to $74m settlement in COVID flight credits class action

2 hours -

Nigeria reviews oil, market exposure amid rising Middle East tension

2 hours -

Shipper MSC secures 45‑year Lagos port concession with Nigerdock

2 hours -

McDan Aviation accuses GACL of defying court injunction in midnight terminal raid

3 hours -

No 90-day notice – McDan Aviation says GACL violated contract in Terminal 1 eviction move

3 hours -

McDan Aviation says GACL actions attempt to collapse indigenous aviation venture

3 hours -

KPop Demon Hunters to return as Netflix announces sequel

5 hours -

ROKA Kids Invitational Marathon returns for 4th edition on March 28

6 hours -

Gratitude and growing pains: Reflections on Ghana’s citizenship ceremony and the future of diaspora return

6 hours -

AI toys for young children need tighter rules, researchers warn

6 hours