You don't need seawater to develop and transform a landlocked city like Kumasi, even if it is possible to embark on a fanciful adventure like diverting part of the Atlantic Ocean from Tema across 275km of land through numerous communities; several forests; many rivers; and countless farmlands in two regions to the Ashanti regional capital. Just look at Johannesburg, South Africa, which became the largest landlocked city in the world and one of the most affluent, with its Sandton district nicknamed "the richest square mile in Africa."

Kumasi, too, can make it without expensive seawater. In fact, it has made it before.

The Kumasi of my childhood, particularly the latter half of the 60s and into most of the 70s, bore testament to that. I consider that period the Golden Age of the Garden City, driven by entrepreneurship and innovation, a diverse and vibrant economy, cosmopolitan social life, and the early flowerings of industrialisation. When “burgers” from West Germany first brought “guarantee” (or platform) shoes to Kumasi, innovative Kejetia shoemakers were quick to use the light wawa wood to manufacture local ones that successfully competed with the imported ones. When foreign briefcases became fashionable in the 1970s Kumasi, the same shoemakers used plywood, thin foam, and black leather to manufacture local versions. Suame became the automotive hub for Kumasi and beyond. And when my cousin, Sowah, finished commercial school at Bantama, he was immediately hired as an accountant by the newly established Neoplan bus assembly plant, one of the earliest pillars of Kumasi’s industrialisation and a contributor to addressing the city’s youth unemployment problem. (Imagine the number of jobs that would be created by Neoplan alone in Kumasi today if it had flourished into a major global manufacturer. Google “Neoplan buses” and see what could have been, instead of imported second-hand buses from Korea).

Civic life in Kumasi was equally great. There was the Ashanti Regional Library (from where I once wrote a letter to US President Richard Nixon and, to my surprise, got a reply); Cultural Centre (or, simply, Cultural, as we affectionately called it); the Kumasi Zoo; the many parks and gardens that gave Kumasi its nickname of Garden City; and the only Olympic-sized swimming pool in Ghana at the time, at Tech, which attracted a mix of locals (rich and regular) and expatriates working at KNUST. In fact, the first time I saw a supermarket was at KNUST, a university town within a city, with its shops, hospitals, schools, and even a police station. And there, on campus, one would occasionally see the son of a lecturer showing off his father’s brand new sports car, a Mustang. There were no commercially imported used cars then. There were even Mercedes taxis.

The overnight trains to Takoradi and Accra had first-class bunk beds for those willing to pay the premium, my sister, a businesswoman, being one. She would travel to Takoradi overnight, do her business during the day, and come back to Kumasi overnight. Local public transport, the Omnibus Service Authority (OSA), functioned efficiently from central Kumasi to outlying areas like Ejisu. Race Course at Bantama on weekends was a sight to behold, attracting bettors in their finest clothes and hats from as far away as Accra.

Kumasi was buei! Life was good.

And then, like the rest of the country, neglect and decay set in in the late 70s, rolling back most of the progress the city had made in its economic development even before independence. Industries declined and most of the first-class infrastructure fell into disrepair. Rather than burgers returning home – with skills ranging from tailoring to anaesthesiology (the first time I heard the word), many unemployed youth left for greener pastures abroad, much like their counterparts around the country.

In a recent television interview, Kumasi-based businessman and one-time presidential candidate, Akwasi Addai Odike, decried how the entrepreneurship spirit of Kumasi had gradually been sucked away in favour of Accra, constraining the ability of local businesses to grow beyond a certain point, unlike in the past. This, he said, had forced many of Kumasi’s restless entrepreneurs to relocate to Accra.

This of course is part of a wider economic and demographic convergence on the national capital, especially in the past 30 years, as national development policies have unfairly neglected the rest of the country in favour of Accra. For example, for years, about 80% of foreign direct investment (FDI) was destined for Greater Accra, with about 10% going to the Ashanti Region, the most populous region. In 2021, Greater Accra, with the smallest land area of 1.4% of Ghana, overtook the Ashanti Region, with over 10% of the land area, as the most populous region in Ghana. The share of FDI going to Greater Accra is now about 85%.

Nobody gains from such structural distortions and lopsided allocation of national resources, including labour. Accra is now overpopulated, severely polluted, and patently dysfunctional, while the rest of the country barely gets by on what little the central government hasn’t taken yet. The sum effect is lower national development, persistently high unemployment, and grinding poverty that affect us all.

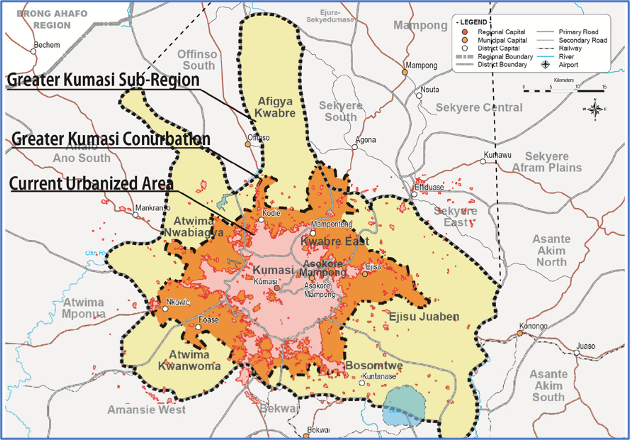

Enter President John Evans Atta Millis. In 2012, he decided to turn Kumasi’s economic fortunes around by initiating the Comprehensive Urban Development Plan for Greater Kumasi, or simply the Greater Kumasi Master Plan. The Plan was based on the most comprehensive socio-economic study ever conducted of Kumasi and was made up of three main volumes and supplementary material totalling over 1,000 pages. It was to transform not just Kumasi City but also seven surrounding communities, namely: (1) Afigya-Kwabre District, (2) Kwabre East District, (3) Ejisu-Juaben Municipality, (4) Asokore-Mampong Municipality, (5) Bosomtwe District, (6) Atwima-Kwanwoma District, and (7) Atwima-Nwabiagya District (see the graph below). It was a truly visionary plan for the creation of a megalopolis in the middle of Ghana.

The Plan had the following vision, “The Greater Kumasi Sub-Region will become a pioneer to transform the current economy to a vibrant, modernised and diversified economy, including commerce, logistics, manufacturing and knowledge-based industries, by creating a liveable, sustainable and efficient urban space, while maintaining the historical and cultural aspirations of the Ashanti Region.” The motto was, “Greater Kumasi Revitalization 2033: The Heart of the Nation.”

Completing the much-delayed Boankra dry port (no sea, only rail and land) and an industrial free zone at Ejisu, were an integral part of this dynamic and ambitious Plan, situated within the larger development prospects of the Ashanti Region. Overall policies were aimed at broad-based socio-economic development (such as industrialisation, housing, open spaces and recreation, and the transformation of the Kumasi City centre, among others), as well as the following: modernised public transportation, including Bus Rapid Transit (BRT); improved water management and supply; effective liquid and solid waste treatment; modern drainage systems, and expanded electricity supply.

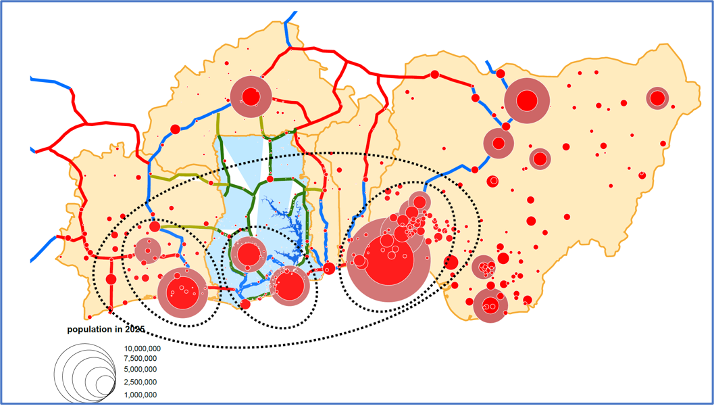

Under the National Spatial Development Framework launched later under President John Mahama, Kumasi was given even greater prominence beyond Ghana to be a major hub in the socio-economic development of ECOWAS and beyond. As shown in the figure below, Kumasi and Accra were designated as “city regions” (in the middle oval) alongside similar city regions in Ivory Coast and Nigeria. (Such regions were defined as those that expand beyond their formal administrative borders and absorb smaller cities and towns, with the dynamism to sustain economic growth and social development). The Kumasi Airport was to be upgraded into an international one to facilitate international trade and travel.

Accra, Kumasi and Ghana's Future in ECOWAS under the Mahama Government

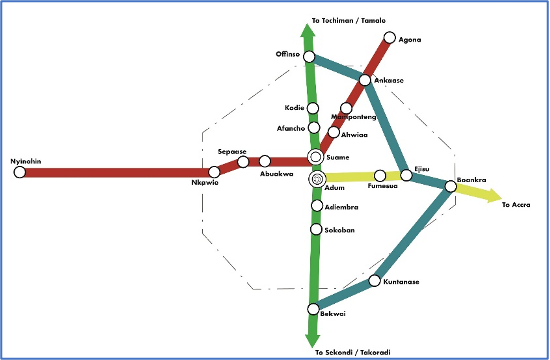

When the Framework was incorporated into the 40-Year National Development Plan, Kumasi once again received special attention. Under the Ghana Infrastructure Plan, part of the 40-Year Plan, it was one of four urban areas that were designated for an urban light rail system to help alleviate its chronic traffic problem and free it for unfettered economic growth (see the graph below). Its past status as a central hub for Ghana’s railway network was to be restored to drive a transport and logistics revolution serving the northern parts of the country and beyond, into Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali.

Greater Kumasi Metro Rail System under John Mahama’s 40-Year Development Plan

The Plan set for 2020 for the completion of the Boankra inland port, with a rail link that would help “reduce pressure at Tema port” and turn the Boankra area into an “international business centre and distribution centre, offering similar services as a seaport…” With services such as a container and storage deport; a railway marshalling yard, and a light industrial zone, the plan listed the following among the socio-economic benefits of the Boankra port: jobs for the youth; reduced aggregate transport cost of international cargo to importers and exporters in the middle and northern parts of Ghana; establishment of export processing zones; and the provision of efficient and safer alternative to road transport.

The idea that Kumasi needs to “pull in” the sea – “like Dubai”- to develop, therefore, makes no sense, even if it is technically possible to do it. Contrary to the propaganda that if Dubai can do so, so can Kumasi, it must be stated that Dubai has always had a coastline, 72 km long, within the Persian Gulf. It owes its development to visionary and dedicated leadership, not sea water drawn from distant lands.

What Kumasi can and should learn from Dubai is visionary and dedicated leadership, free of petty politics, that would fully implement the Mills-Mahama transformation agenda for the Garden City and its environs with the urgency it deserves.

Anaa me boa?

******

The author is a former Director-General of the National Development Planning Commission, which prepared the 40-Year National Development Plan, and a leading advocate for the Greater Kumasi Master Plan.

Latest Stories

-

Elevating Ghana’s creative industry: A blueprint for competing with Nigeria and South Africa

1 hour -

Poor finishing a problem for Asante Kotoko throughout the season – Prosper Ogum

1 hour -

Samini teams up with Francis Osei for ‘Sticks N Locks’ EP

2 hours -

Government should resource record labels – Seven Xavier

2 hours -

I need majority in parliament to successfully complete my term – Akufo-Addo pleads

2 hours -

Next NDC government will not recognise illegal contracts signed by current administration – Sammy Gyamfi

2 hours -

Premier League clubs vote in favour of spending cap plans

2 hours -

Nigeria’s fuel crisis brings businesses to a halt

2 hours -

King Promise impresses fans at sold out show in Singapore

2 hours -

Ejisu by-election to proceed after plaintiff withdraws injunction application

2 hours -

CSOs and NGOs unite to push for priority demands at INC-4

3 hours -

Fuel tanker bursts into flames on Kumasi-Accra highway

3 hours -

EC’s stolen BVR kits, laptops: One granted bail, three still on remand

3 hours -

2 Things: Sista Afia releases first song off her upcoming album

3 hours -

GHS to embark on COVID-19 vaccination campaign starting May 4

3 hours