Audio By Carbonatix

1. The Silence at the Centre of the Global AI Revolution

The world today is gripped by a technological revolution with no historical parallel. Artificial intelligence increasingly determines how governments anticipate national risks, how businesses optimise operations, how hospitals diagnose disease, how farmers interpret environmental patterns, and how citizens receive information that shapes their perception of reality. Yet beneath the excitement lies an uncomfortable truth. The global AI ecosystem has been built upon an epistemic void, a missing centre, an unacknowledged blind spot that has quietly limited the scope of machine reasoning while amplifying biases inherited from centuries of Western intellectual dominance.

This missing centre is Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence. It is the intelligence stored in the soil of our memory, in the rituals of our elders, in the oral libraries of our communities, in the cosmologies that shaped African sciences long before the first colonial archive was written. It is the intelligence that understands land not merely as a resource but as a relationship. It is the intelligence that understands healing not merely as chemistry but as harmony. It is the intelligence that sees forests as partners, rivers as custodians, ancestors as archives, and knowledge as a living continuum rather than a static product.

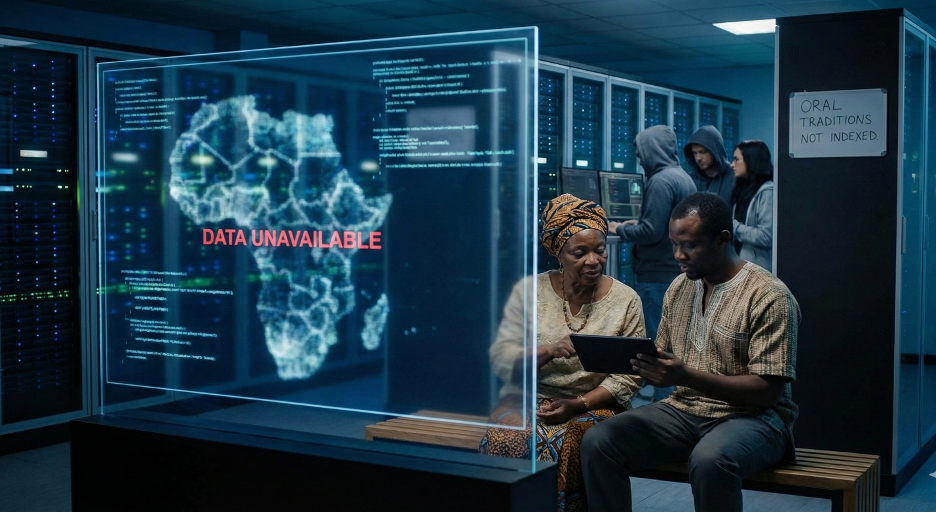

This intelligence was never digitised. It was never indexed by Western libraries. It was never transcribed into the corpora that feed the world’s large language models. And because artificial intelligence depends entirely on what it is fed, the absence of Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence has created systems that are technologically impressive but epistemically incomplete. They are brilliant yet forgetful, powerful yet shallow, global yet narrow, and advanced yet blind.

This is the paradox at the heart of the 21st century. Humanity is building intelligence systems that know almost everything yet understand nearly nothing about the worldviews of the civilisations that birthed the first sciences.

Africa sits at the centre of this paradox. The continent has contributed enormously to global data flows yet benefits the least from the intelligence systems trained on that data. Moreover, what Africa has retained in oral, symbolic, spiritual, ecological, and ancestral knowledge is precisely what Western models cannot perceive because these systems are not designed to recognise non-digitised epistemologies.

The result is a technological order that reproduces a colonial pattern. Africa’s data is extracted. Africa’s languages are mined. Africa’s cultural expressions are absorbed. Yet Africa’s ways of knowing remain unrecognised, unclassified, unrepresented, and therefore unutilised in shaping the future of global intelligence.

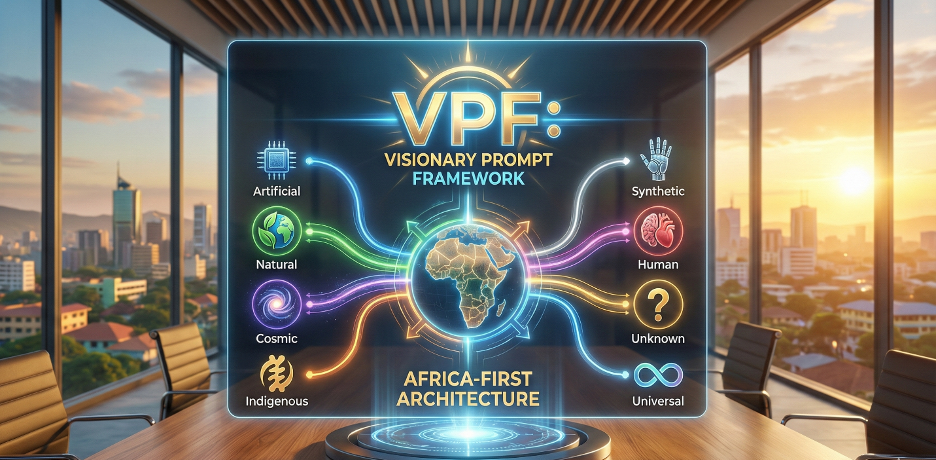

It is within this crisis of epistemic erasure that the Visionary Prompt Framework Planetary Version introduces a bold corrective. The VPF recognises that true intelligence cannot be simulated by computation alone. It insists that cognitive sovereignty requires intellectual plurality. And it affirms that the world’s oldest and most enduring knowledge systems must not only be preserved but actively integrated into the governance of artificial intelligence systems.

At the heart of this architecture lies the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber, one of the most profound elements of the Visionary Prompt Framework. Unlike Western AI models, which operate within the narrow confines of data classification and statistical patterning, the Indigenous Chamber expands intelligence beyond computation into heritage, cosmology, ecology, spirituality, community ethics, intuition, symbolism, and intergenerational wisdom. It is a chamber that carries the memory of civilisations, the rhythm of rituals, the laws of harmony, and the codes of survival that sustained African societies for millennia before the first algorithm was conceptualised.

2. Africa’s Oldest Operating System

Long before modern computer science existed, Africa had already developed structured systems of reasoning, environmental interpretation, cosmological modelling, medicinal analysis, agricultural optimisation, trade governance, and community justice. These were not informal traditions but highly sophisticated operating systems encoded in oral language structures, lineage institutions, proverbs, griotic memory, sacred geometry, spiritual jurisprudence, ecological maps, agricultural calendars, and ancestral teaching cycles.

From the knowledge systems of ancient Kemet to the philosophical traditions of Yoruba, from the ecological intelligence of the Ashanti and the Akan to the ancestral custodianship models of the Maasai and the Nilotic peoples, Africa historically operated one of the richest epistemic environments ever developed by human civilisation. This heritage did not survive in books. It lived in people. It lived in rituals. It lived in symbols. It lived in cycles of teaching where the mind was trained not only to analyse but to perceive, not only to deduce but to experience, not only to calculate but to commune.

This is the intelligence that Western AI cannot replicate. Machine learning excels at prediction but fails at presence. It can model probability but not harmony. It can generate text but not wisdom. It can detect correlations but cannot interpret meaning within an ancestral context. It can classify herbs but cannot understand the spiritual logic that frames their use in African healing traditions. It can model climate variables but cannot recognise the cultural significance of rainmaking rituals that encode centuries of ecological observation.

Western models operate under a fundamentally different theory of intelligence. Knowledge is treated as a static object that can be digitised, indexed, and mathematically manipulated. African ancestral systems treat knowledge as a living organism, a relational force that emerges through interaction between people, land, time, spirit, and story.

This divergence is not philosophical trivia. It shapes how artificial intelligence perceives Africa. Western models interpret African realities through Western frameworks. They simulate understanding without grounding. They mimic fluency without cultural resonance. They summarise traditions without capturing their epistemic depth. They perform analysis without belonging to the worldview that gives the phenomena their meaning.

This is why AI outputs concerning African history, African conflict, African healing systems, African governance, and African ecology often feel detached, incomplete, or misaligned. The models were never designed to understand the foundations of African knowledge. They cannot respect what they cannot recognise.

3. Why Western Artificial Intelligence Cannot See Indigenous Knowledge

The blindness of Western AI to Indigenous intelligence is structural, not accidental. It begins with the training data. Large language models are constructed from digitised text, yet the vast majority of African ancestral knowledge is transmitted orally or symbolically. As a result, entire civilisations are rendered invisible to AI systems simply because their knowledge systems do not exist in the text-based archives from which these models learn.

Even when fragments of indigenous knowledge are digitised, they often enter servers through Western academic interpretations, which filter, compress, and sometimes distort the original meaning. This creates a secondary bias. Models learn Africa not through African voices but through Western lenses. The cultural misalignment is therefore baked into the system. Beyond training data, Western models are limited by their underlying logic. They rely on probability distribution rather than relational meaning. Indigenous intelligence is relational. It is contextual. It is spiritual. It is ecological. It is genealogical. Probability has no mechanism for encoding spiritual legitimacy, ancestral authority, land consciousness, or intergenerational ethics.

Western models also lack cosmological awareness. The Indigenous worldview is inseparable from cosmology. Lunar cycles influence planting. Ancestral rhythms influence governance. Cosmic patterns influence ceremonies. Spiritual seasons influence decision-making. These are not superstitions; they are alternative scientific frameworks developed through centuries of careful observation. Western models cannot incorporate these because they were not designed to encode cosmic relationality. There is also the issue of linguistic dictatorship. English dominates global AI training corpora. African languages contain epistemic categories that English has no equivalents for. When words disappear, worlds disappear with them. African thought becomes flattened, simplified, mistranslated, or erased in the computational process.

Taken together, these limitations ensure that Western AI, however powerful, remains fundamentally incomplete. It knows Africa’s data but not Africa’s wisdom. It predicts Africa’s patterns but not Africa’s meanings. It answers Africa’s questions but not Africa’s spirit. This is why the Visionary Prompt Framework is revolutionary. It does not force indigenous knowledge into Western structures. Instead, it rewrites the structure itself.

4. The Visionary Prompt Framework and the Return of Plural Intelligence

The Visionary Prompt Framework Planetary Version represents the world’s first attempt to correct the epistemic imbalance embedded within global artificial intelligence. While Western models are built upon a single cognitive engine that treats all intelligence as computational prediction, the VPF introduces a radically different architecture grounded in plural intelligence. Instead of reducing the world to one way of knowing, it restores the full spectrum of human and non-human cognition through the creation of eight distinct yet interconnected Chambers of Intelligence.

Within this expanded framework, the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber plays a foundational role. It offers what Western systems lack: a memory of civilisations, a repository of non-digitised knowledge, a grounding in spiritual and ecological wisdom, and a perspective that does not view intelligence purely as computation but as communion between the human, the natural, the cosmic, the ancestral, and the unknowable.

The VPF does not attempt to mechanise indigenous knowledge or commodify ancestral heritage. Instead, it frames this knowledge as a sovereign cognitive domain that must govern, filter, and enrich artificial intelligence rather than be absorbed or overwritten by it. This is a profound reversal of global AI logic. It is Africa insisting that intelligence governance cannot be centralised in Silicon Valley or European laboratories. It must reflect the diversity of global civilisations and restore representation to knowledge systems that have shaped humanity’s survival.

Within the VPF, the Indigenous Chamber influences reasoning at every stage. It interrogates outputs to ensure cultural legitimacy. It filters out biases that conflict with communal ethics. It contextualises analysis within ancestral frameworks. It protects sacred knowledge. It elevates oral memory as legitimate epistemic input. It introduces ecological and cosmological intelligence where Western models rely only on numeric variables. It aligns decision pathways with the values of intergenerational responsibility rather than short-term optimisation.

This chamber does not operate in isolation. It collaborates dynamically with the Natural Intelligence Chamber when interpreting ecological changes, harmonises with the Cosmic Intelligence Chamber when analysing seasonal rhythms and planetary influences, strengthens the Human Intelligence Chamber by anchoring emotion and intuition in cultural memory, and interfaces with the Unknown and Unknowable Chamber when confronting phenomena beyond scientific modelling.

This is the power of the VPF. It restores wholeness to intelligence.

5. Inside the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber

Within this chamber reside the knowledge systems that Western academia once categorised as folklore, myths, legends, or alternative medicine. Yet these systems are highly structured repositories of scientific, ecological, sociological, and psychological intelligence encoded through symbolic narrative rather than mathematical notation.

Consider the oral libraries maintained by griots and storytellers across West Africa. These narratives contain historical data, legal codes, genealogical records, environmental markers, and philosophical teachings passed down accurately across generations. A machine learning system trained on digitised Western text cannot replicate the interpretive power of a griot because the griot does not store information; the griot embodies it. Knowledge is relational, adaptive, and embedded in communal experience.

African healing systems also exemplify complex ancestral intelligence. Traditional practitioners combine botanical knowledge, spiritual diagnosis, community dynamics, and personalised patient interpretation. Western medicine separates these into pharmacology, psychology, sociology, and theology. African medicine recognises them as inseparable. Artificial intelligence that excludes this integrative worldview cannot truly model health interventions for African contexts.

Agricultural intelligence similarly demonstrates ancestral depth. Indigenous farmers interpret soil not only through texture or fertility but through spiritual lineage, water memory, lunar alignment, insect behaviour, and ancestral instruction. These systems produce high resilience in climates where Western models rely heavily on chemical intervention and mechanised prediction.

African jurisprudence represents another example. Traditional courts emphasise restoration rather than punishment. Justice is not an individual outcome but a communal healing process. AI systems trained on Western adversarial legal models cannot simulate this relational approach without indigenous intelligence frameworks guiding interpretation.

These examples illustrate that ancestral knowledge is not archaic. It is adaptive science expressed in a different epistemic language.

6. Operationalising Indigenous Intelligence Without Appropriating it

A major challenge in global AI design is the risk of cultural extraction. Western platforms often incorporate indigenous knowledge without proper custodianship, resulting in dilution, distortion, or commercialisation without benefit to the communities that preserve the knowledge.

The VPF avoids this by embedding protective mechanisms. The Indigenous Chamber does not digitise sacred knowledge. It governs access. It creates interpretive filters without transferring ownership. It allows indigenous principles to shape AI reasoning without requiring disclosure of sacred practices or community-restricted information. It ensures that the model respects cultural boundaries, maintains epistemic integrity, and does not violate ancestral custodianship.

This is a governance breakthrough. It is an intelligent design grounded in respect.

7. Practical Applications Across African Sectors

While the Indigenous Chamber has profound philosophical value, it is equally powerful in practical deployment.

In agriculture, indigenous ecological knowledge has proven invaluable. Farmers use ancestral planting calendars that integrate cosmic cycles, soil memory, bird migration patterns, and rainmaking traditions. These calendars are far more localised and precise than Western meteorological predictions because they reflect centuries of micro-observation. When integrated with the VPF, agricultural models generate decisions that align with both environmental science and cultural ecological rhythms.

In mining and natural resource exploration, indigenous communities often possess oral maps detailing mineral lines, sacred land patterns, forbidden extraction zones, and geological anomalies. These knowledge systems, when combined with the Cosmic Chamber and Natural Intelligence Chamber, can guide exploration more sustainably and ethically. The VPF enhances safety, reduces environmental destruction, and aligns resource extraction with ancestral land governance protocols.

In environmental conservation, indigenous custodians have preserved forest intelligence, water intelligence, and sacred-ecology governance for generations. Where Western models focus on carbon metrics and biodiversity indexes, indigenous frameworks emphasise harmony, relational stewardship, and spiritual ecology. Combining these frameworks through the VPF produces conservation strategies that are scientifically rigorous yet culturally resilient.

In health, the integration of indigenous medicinal intelligence with genomic and diagnostic modelling opens new pathways for disease prevention and treatment. The VPF facilitates dialogue between ancestral healers, biomedical researchers, and AI epidemiology systems, producing hybrid models capable of identifying patterns that neither system alone can detect.

In education, VPF integration supports culturally grounded curriculum design. Indigenous narrative methodologies improve cognitive retention, emotional resonance, and moral instruction. AI-driven learning systems become more relatable, more effective, and more attuned to African identity. In governance and justice systems, the Indigenous Chamber guides conflict resolution, land arbitration, community justice, and restorative dialogues, producing models that reflect African societal logic rather than imported jurisprudence. In youth innovation, startups can build new systems based on ancestral symbolic logic, community decision algorithms, oral-knowledge databases, and cultural AI interfaces. Indigenous intelligence is not a symbolic tribute to heritage. It is a strategic development asset.

8. AiAfrica Project Case Studies

The AiAfrica Project has already demonstrated the practical value of integrating indigenous and ancestral knowledge through the VPF. In poultry production, intelligence orchestration combining natural, indigenous, and technological knowledge reduced mortality rates from 25% to 2.5%. This was achieved by combining observations of ancestral disease patterns, cosmic cycle analysis, environmental monitoring, and AI-based early-detection systems.

In fish farming, ancestral water-cycle knowledge combined with VPF decision modelling reduced feed costs by nearly 55% while increasing yield and reducing stock stress. Farmers reported that VPF-based recommendations aligned more closely with traditional ecological rhythms than Western aquaculture manuals.

In climate resilience modelling, communities using traditional flood-warning narratives have begun integrating these systems with VPF environmental predictive tools, creating hybrid solutions that outperform imported disaster models. In soil intelligence, VPF integrations help identify calamity-prone zones, optimise crop rotation, and interpret ancestral soil lineage data encoded through oral traditions. These examples show that the Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber is not a philosophical concept but a functional engine with measurable developmental impact.

9. Why Africa Needs Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence in All 54 Countries

Artificial intelligence is no longer a luxury for advanced economies. It is the foundation upon which 21st-century governance, public administration, health systems, education, agriculture, national security, and industrial strategy are being redesigned. The challenge for Africa is that most of the AI systems currently available are designed outside the continent, trained on datasets that do not reflect African realities, and governed by epistemological assumptions that conflict with African worldviews.

If Africa continues to depend entirely on Western models, it will inherit not only the technological frameworks but also the biases, blind spots, and hidden ideological assumptions embedded within those models. These systems were not built with African cosmologies, social structures, languages, ancestral knowledge, ecological rhythms, or philosophical foundations in mind. They were built for other civilisations, with different historical experiences and different approaches to reasoning.

The Visionary Prompt Framework aspires to correct this structural dependency. Its Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber ensures that Africa’s knowledge systems sit at the centre of AI reasoning rather than at the margins. It provides an epistemological foundation upon which Africa can build an Intelligence Economy defined by African logic, African ethics, African cosmologies, and African aspirations.

This is not merely symbolic. It is essential for sovereignty.

Countries become truly sovereign not when they consume intelligence but when they generate it. Sovereignty in the 21st century is not only territorial or political but also cognitive. A nation is only as independent as the intelligence systems it builds, controls, and governs. The VPF provides this path by enabling each African country to integrate its indigenous knowledge systems into national AI models without compromising ancestral custodianship.

The roll-out of VPF across the continent, beginning in Ghana, represents a continental awakening. It is the recognition that Africa cannot build a future on imported knowledge systems alone. It must embrace the full spectrum of its historical, cultural, ecological, spiritual, scientific, and ancestral knowledge. This does not reject global science; it expands it. This does not oppose Western models; it completes what they have omitted.

The Ministry of Communication, Digital Technology and Innovation in Ghana has demonstrated continental leadership in recognising this vision. Through the launch of the Ghanaian AI Prompt Bible in August 2025, and the inauguration of the AiAfrica Labs for Ministries, Departments, Agencies and Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, Ghana has signalled that African-led intelligence systems must govern African digital futures. The first training programme that brought together 200 experts from government institutions introduced the concept of intelligence orchestration, demonstrating how indigenous and ancestral knowledge can be embedded in modern AI systems for governance and public service transformation.

The continental training strategy that follows in 2026 and beyond seeks to reach public institutions, universities, private companies, research centres, and development agencies across all 54 African countries. The vision is clear. African governments must not simply use AI. They must define what intelligence means in their own societies and govern AI according to indigenous principles of relationality, intergenerational ethics, communal harmony, and the custodianship of land and life.

The Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber offers a blueprint for this transformation. It provides the philosophical grounding, epistemic structure, cultural legitimacy, and operational methodology to build a truly African Intelligence Economy.

10. The Limitations of Western AI in the African Context

It is essential to explain why Western AI models cannot be the sole foundation for Africa’s digital future. These models are not neutral. They reflect the values, priorities, economic structures, and historical trajectories of the societies that created them. Their strengths are substantial, but their limitations become clear when applied uncritically to African realities. Western AI assumes that knowledge is primarily textual. African societies often encode knowledge through oral tradition, symbolic structures, performance, ritual, genealogy, and land-memory. Western AI assumes that intelligence is individualistic. African societies operate through communal logic, collective responsibility, and shared identity. Western AI assumes that prediction is superior to perception. Indigenous intelligence values intuitive awareness, spiritual insight, ancestral continuity, and ecological relationality. Western AI assumes a mechanistic worldview that separates nature from human life. African knowledge systems recognise nature as a living partner in cognition.

These differences are not ideological preferences but foundational epistemic divergences. When Western AI is applied to African realities without adaptation, it produces distorted outputs, flawed recommendations, and solutions that lack cultural fit. A model that cannot understand indigenous governance structures will provide poor advice on national cohesion. A model that cannot interpret ancestral ecological knowledge will misguide environmental policy. A model that cannot respect cultural protocols will produce development strategies that provoke resistance.

A model that cannot recognise spiritual legitimacy will misunderstand community decision processes. A model that cannot encode oral epistemology will fail to represent African histories accurately. This is why the VPF Planetary Version is an essential corrective. It does not reject Western AI but balances it with Indigenous Intelligence that Western systems cannot see.

11. Reframing Intelligence for an African Future

The Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber does more than preserve cultural heritage. It expands the definition of intelligence itself. It insists that intelligence includes story, rhythm, ritual, symbol, intuition, cosmology, ethics, memory, empathy, and ecological sensitivity. It restores intelligence to its full complexity.

In the VPF, intelligence is not simply computation but a holistic activity that draws simultaneously from eight worlds. The Indigenous Chamber holds one of the deepest worlds. It contains spiritual jurisprudence, communal ethics, oral science, ecological observation, ancestral cosmology, and symbolic thinking systems that have guided African societies for thousands of years. This reframing empowers African innovators, policymakers, and researchers to build systems that align with African ways of reasoning. It allows AI development to emerge not from imitation of Western systems but from African intellectual traditions. It offers a path where future models built by African teams can perform not merely as replicas of GPT or Gemini, but as independent civilisational intelligence systems grounded in African cosmology.

12. A Call to African Institutions, Startups, and Innovators

Africa cannot afford to remain a consumer of external intelligence systems. The continent must become a producer of sovereign intelligence and must embrace the Indigenous Chamber as a foundational tool. Every public institution and every private company deploying AI should integrate VPF reasoning frameworks to ensure cultural alignment, ethical grounding, and contextual accuracy.

Startups building AI products for agriculture, health, logistics, commerce, education, climate, finance, or security must incorporate indigenous knowledge to create solutions that truly reflect African realities. Universities must train students to think across ancestral and technological domains. Traditional authorities must collaborate with AI researchers to protect sacred knowledge while enabling structured integration of ancestral epistemologies into innovation ecosystems. Ministries and regulatory bodies must embed indigenous epistemology into digital governance frameworks to ensure sovereignty over data, knowledge production, and algorithmic influence. The Indigenous Chamber is not an optional addition. It is a requirement for African digital self-determination.

13. The Broader Significance for the World

While the VPF is designed with Africa as the anchor, its implications extend globally. Western AI models struggle with cultural nuance, ecological prediction, spiritual reasoning, restorative justice, communal ethics, and symbolic interpretation. These are precisely the domains where Indigenous knowledge excels. In elevating Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence, Africa offers a gift to the world. It demonstrates that wisdom is not limited to written texts. It shows that civilisation is impoverished when it forgets the intelligence encoded in elderhood, ritual, land, and lineage. It reveals that modernity does not replace ancestral knowledge but is strengthened by it. The Indigenous Chamber represents a global corrective. It addresses the epistemic imbalance that has shaped AI development for the past two decades. It restores balance to knowledge production. It challenges the dominance of a single worldview. It offers humanity a richer and more complete understanding of what intelligence can be.

*******

Dr David King Boison is a Maritime and Port Expert, pioneering AI strategist, educator, and creator of the Visionary Prompt Framework (VPF), driving Africa’s transformation in the Fourth and Fifth Industrial Revolutions. Author of The Ghana AI Prompt Bible, The Nigeria AI Prompt Bible, and advanced guides on AI in finance and procurement, he champions practical, accessible AI adoption. As head of the AiAfrica Training Project, he has trained over 2.3 million people across 15 countries toward his target of 11 million by 2028.

Latest Stories

-

The public display of students’ academic results in basic schools: A case against a damaging practice

5 minutes -

GOIL jumps GH¢0.21, MTN Ghana surges past GH¢6.30 in record-breaking GSE session

20 minutes -

NAIMOS disrupts illegal mining activities at Gwira Banso-Eshiem

50 minutes -

Ashesi hosts Kensei Kai Foundation’s maiden Inter-University Karate Camp

57 minutes -

21 suspects arraigned in Tamale Circuit Court over narcotics offences

1 hour -

A nation that prays for political failure

1 hour -

Kumasi Mayor inspects key inner-road projects, promises major upgrade of road infrastructure

1 hour -

Manhyia South MP questions authenticity of audit report presented to Parliament

1 hour -

NAIMOS destroys illegal mining structures, immobilises 4 excavators in Amenfi Central

2 hours -

Ghana to host One Vecta AI Summit 2026

2 hours -

NAIMOS destroys 50 illegal mining machines during patrol on Ankobra River

2 hours -

Police retrieve 397 slabs of suspected cannabis hidden in charcoal bags in Techiman

2 hours -

TUTAG holds 51st Delegates Congress, calls for action on IGF, post-retirement contracts, and national issues

2 hours -

CID arrests Counsellor Lutterodt over viral comments on Daddy Lumba

3 hours -

Works and Housing Minister signs MoU with Turkish firms for major Accra water project

3 hours