Audio By Carbonatix

As we wrap up programming on this site for the holiday break, I thought I should give readers a parting shot from the katanomics stable.

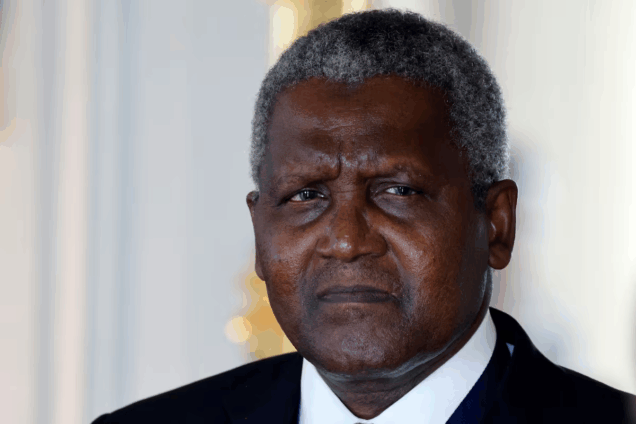

And who better to use than Aliko Dangote, the richest Black billionaire in the world, and arguably the most consequential industrialist Africa has produced since independence.

The Dangote story holds much fascination for some of us in the policy activism space. I have found that in elite Nigerian circles, admiration often gives way to discomfort. Accusations range from monopolistic behaviour to regulatory capture and policy bending. How can one man/company attract so much admiration and fear/opposition in the same measure?

In typical katanomics fashion, one has to move closer and dive deeper to get something close to an answer. That answer is thrilling and unsettling. Dangote is far from the paradigm-shattering and mould-breaking actor he is sometimes held up to be by both his foes and his admirers. His entire phenomenon is a rational response to a profoundly broken policy environment. The kind of environment best described by the katanomics label.

Katanomics describes a fracture between politics and policy. Between grand national ambitions and the granular, technical execution required to realise them. Nigeria, like many African states, is awash with industrial master plans, indigenisation roadmaps, and self-sufficiency proclamations. The failure lies far less than most people assume in political vision and ambition and almost entirely in a particular framework, or lack of framework, in policy execution. Nor is corruption the central feature. Far from it, corruption is but a symptom. The truth is that Political accountability has improved over the years. The tragedy is that policy accountability has not.

Nowhere is this clearer than in oil.

Nigeria holds roughly 37 billion barrels of proven reserves, yet struggles to sustain 1.5 – 1.8 million barrels per day of production in good years. Petrobras of Brazil, with just 10.4 billion barrels, produces nearly 2.7 million bpd. Petronas, which once massively lagged NNPC in output, now posts over $30 billion in operating profit annually, while NNPC’s ₦2.5 trillion profit in 2022 (≈$5.4bn) masks decades of capacity erosion.

Policy mis-calibration is, from the standpoint of the katanomics theory, the chief culprit. Nigeria’s shift from Joint Ventures to Production Sharing Contracts solved short-term cash-call failures while institutionalising cost inflation (“gold-plating”). Deep-water royalty holidays and weak audit capacity quietly transferred billions in rent to international operators. As the need for policy-detail cascading increased, public discourse remained stubbornly political, completely out of sync. The result was inevitable: sovereign ownership without sovereign capability.

Manufacturing tells the same story.

Cement is often hailed as Nigeria’s industrial miracle. Capacity exploded from under 2 million tonnes to over 50 million tonnes, and Nigeria became a net exporter. But prices remain among the highest globally, protected by import barriers that transferred consumer surplus to producers. Sugar followed the same template. Then it collapsed. By 2020, Nigeria still imported over 1.5 million tons annually, spending $433 million in forex, while domestic production met less than 5% of demand.

Dangote’s own balance sheets reveal the pattern. Dangote Sugar’s gross margins fell from nearly 30% in the mid-2000s to under 5% by 2024, crushed by FX exposure and finance costs. Cement margins, by contrast, remain near 50% in Nigeria, double those of its Pan-African operations. As these moats narrow, capital escalates.

The difference? Cement’s value chain is simple, requiring minimal policy-orchestration and mineral-anchored. Sugar requires land aggregation, irrigation, and social coordination, a degree of policy intensity that Nigeria has not been able to sustain.

Enter the $20+ billion Dangote Refinery.

Understanding Dangote’s forays in this space, including his recent combat with regulators, requires an understanding of the group’s “capital escalation” and “policy-political consolidation” strategy as a rational response to the katanomic environment.

After watching margins in its sugar operation crumble (see chart below), and the strategic moat around cement start to crack, Dangote doubled down by catapulting the capital escalation projectile: a massive petrochemical complex designed to process 650,000 barrels per day in a single train.

The refinery should have been fed by Nigerian crude. Instead, it imports oil from the United States and Brazil because over 270,000 bpd of NNPC’s equity crude is pledged to debt-collateralisation schemes. The refinery now relies on Naira-for-Crude arrangements, Free Trade Zone shields, and 4,000 CNG trucks costing ₦720 billion to bypass a vandalised pipeline network. Yet, the plan is to expand output to 1.4 million barrels.

It is easy to see this in easy binary terms: lovers hail vision, and haters lament corporate excess or even greed. It is principally an adaptive behaviour in a katanomic system where policy learning collapses and scale becomes the only defence.

Dangote is not bending Nigeria to his will. Nigeria’s broken policy architecture is bending Dangote.

Read the detailed essay here: https://tinyurl.com/KataDangote

Happy holidays, everyone!

Latest Stories

-

NAIMOS has failed in galamsey fight; it’s time for a state of emergency – DYMOG to President Mahama

49 minutes -

Mahama to open African Court judicial year in Arusha, mark 20th anniversary

55 minutes -

Ghana begins partial evacuation of Tehran Embassy as Middle East tensions escalate

1 hour -

EPA tightens surveillance on industries, moves to cut emissions with real-time monitoring system

1 hour -

Police conduct show of force exercise ahead of Ayawaso East by-election

3 hours -

Ghana launches revised Early Childhood Care and Development Policy to strengthen child development framework

3 hours -

AI to transform 49% of jobs in Africa within three years – PwC Survey

4 hours -

Physicist raises scientific and cost concerns over $35m EPA’s galamsey water cleaning technology

4 hours -

The road to approval: Inside Ghana’s AI strategy and KNUST’s leadership

5 hours -

Infrastructure deficit and power challenges affecting academics at AAMUSTED – SRC President

5 hours -

Former US diplomat sentenced to life for abusing two girls in Burkina Faso

5 hours -

At least 20 killed after military plane carrying banknotes crashes in Bolivia

5 hours -

UK reaffirms investment commitment at study UK Alumni Awards Ghana 2026

5 hours -

NCCE pays courtesy call on 66 Artillery Regiment, deepens stakeholder engagement

5 hours -

GHATOF leadership pays courtesy call on Chief of Staff, Julius Debrah

5 hours