Audio By Carbonatix

Fourteen years after oil first trickled out of the Jubilee field, Ghana has little to show for the windfall.

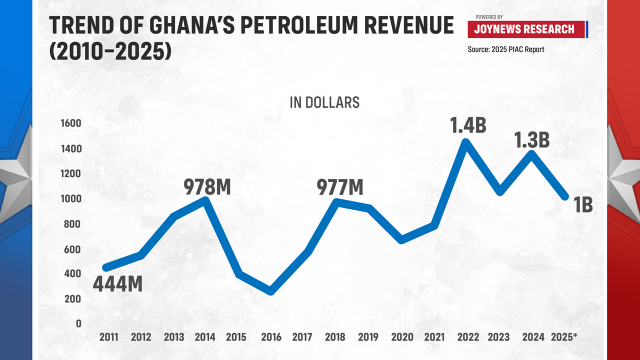

Since 2011, the state has earned about $11.58 billion from crude production, yet the transformation once promised has proved elusive.

The state’s share comes from royalties of 5% to 12.5%, surface rentals of $30 to $100 per square kilometre, a 15% minimum carried interest, a 35% corporate income tax and a mix of negotiated bonuses and other entitlements with each operator.

These inflows peaked in 2022, when the government collected $1.43 billion, but production has faltered since.

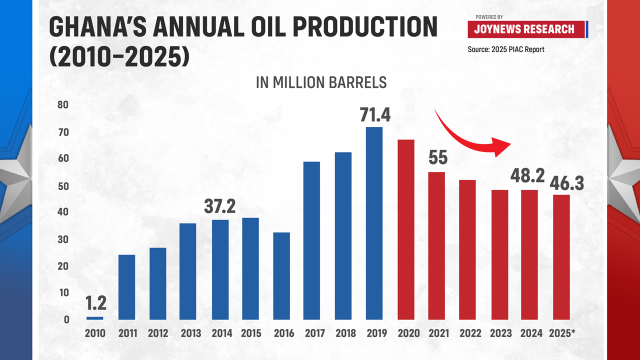

Output has fallen steadily since 2019, weakening state revenues year after year.

In the first half of 2025, receipts dropped to $370 million. That's less than half of the $840 million earned a year earlier. A sharply appreciating cedi eroded the dollar value of these inflows even further.

In all, Ghana has pumped around 675 million barrels of crude since 2010.

The question today is not whether the country has benefited from petroleum, but how far the money has carried it.

Through the Africa Extractives Media Fellowship (AEMF), led by Newswire Africa and the Australian High Commission, Isaac Dwamena, coordinator of the Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC), the independent body that monitors the use of Ghana’s petroleum revenues, outlined how the state has handled the cash so far.

Under the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, all petroleum income flows first into a central account, the Petroleum Holding Fund (PHF), before being shared among key recipients.

The Ghana National Petroleum Corporation has received about $3.15 billion to finance operations and exploration.

Another $2.6 billion has been paid into the Ghana Stabilisation Fund to cushion fiscal shocks, while the Ghana Heritage Fund, reserved for future generations, has received $1.1 billion and now holds roughly $1.3 billion.

The largest visible impact has come through the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA), which has absorbed about $4.5 billion since 2011 and supports the government’s yearly budget, making it the channel through which most citizens feel the benefits of oil revenue.

These ABFA resources have financed headline projects including Kotoka Airport’s Terminal 3, the Kojokrom–Tarkwa railway, the Axim coastal protection works, the Tamne irrigation scheme, Free Senior High School and the Atuabo gas processing plant.

The investments are visible enough, yet many Ghanaians still wonder whether the wider promise of oil wealth has translated into everyday improvements.

Mr Dwamena argues that spending has lacked a clear guiding framework.

Ghana still has no long-term national development plan approved by Parliament to steer the use of petroleum revenues.

The absence of such a plan, he says, has produced a patchwork of projects launched at once, stretching resources thin and creating bottlenecks, delays and cost overruns.

A new shift is also taking shape in how petroleum funds are allocated.

Under the 2025 budget, the government has directed 95% of the ABFA into its Big Push programme to accelerate major road construction nationwide. The remaining 5% goes to the District Assemblies Common Fund.

It is a sharp pivot from previous years, concentrating almost the entire ABFA on a single priority rather than spreading it across several sectors.

Fourteen years after first oil, the gains remain uneven.

Ghana’s experience contrasts with that of Norway, which channels oil income into a large sovereign wealth fund, invests almost entirely abroad and limits withdrawals to preserve capital for the long term.

Ghana’s own rules for managing petroleum wealth were drafted more than a decade ago. They now require fresh scrutiny.

Public consultations, expert input and legislative review could help adapt the framework to today’s economic pressures and the coming energy transition.

Citizens have seen how the laws they helped craft have worked in practice; they must now consider whether the current system delivers what they intended.

For now, Ghana’s oil money has built airports, schools and pipelines. What it has not yet delivered is the economic transformation its discovery once promised.

Latest Stories

-

Regular check-ups key to early diagnosis of medical condictions – Little Angels Trust founder

57 seconds -

Four injured Ghanaian soldiers responding to treatment, likely to be managed in Lebanon — GAF

6 minutes -

Temporary traffic changes announced on Accra–Tema Motorway for major construction works

7 minutes -

New UCC E-Campus to be launched in August 2026; set to admit 10,000 students annually

11 minutes -

IMCC engages Roads Ministry on strengthening devolved sector functions

12 minutes -

One dead in crash at Teacher Mantey on Accra–Kumasi highway

21 minutes -

Istanbul’s ex-mayor to stand trial on corruption charges

22 minutes -

Contractors supplying school feeding programme import rice instead of buying from local farmers — Dr Nyaaba

26 minutes -

Nkoko Nkitinkiti initiative to cut Ghana’s poultry imports — John Dumelo

34 minutes -

The mirage of president’s special initiatives—Mahama’s “legacy projects” or another monument of waste?

48 minutes -

Thousands face long queues at airports in Houston and New Orleans

51 minutes -

‘Night turned into day’: Iranians tell of strikes on oil depots

58 minutes -

Prof. Douglas Boateng commends govt’s value for money agenda, urges passage of Procurement Bill

58 minutes -

Create conducive business environment for farmers to thrive — Dr Charles Nyaaba urges gov’t

59 minutes -

Alleged Bondi gunman seeks order to suppress family’s identity

1 hour