Audio By Carbonatix

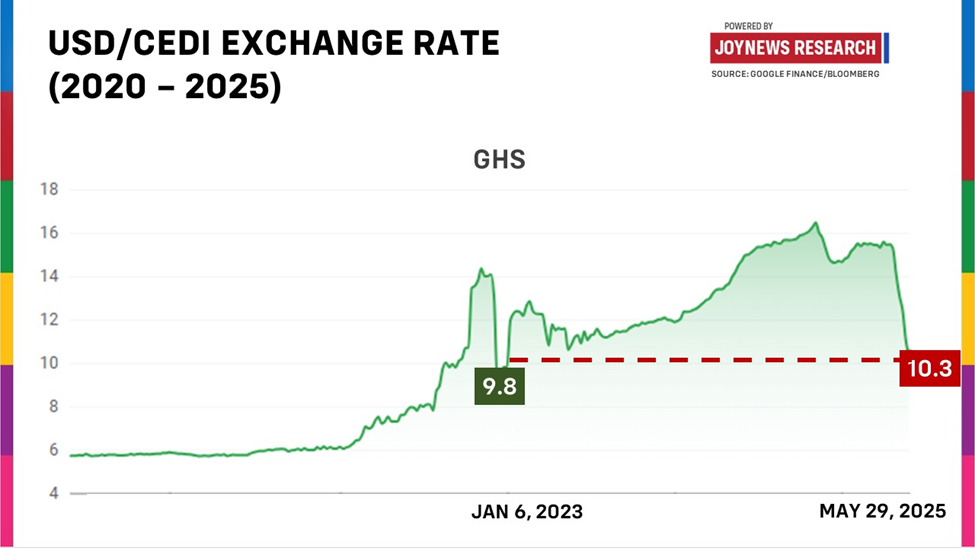

From ending 2024 at $1 to GH₵14.70, the cedi has appreciated nearly 30% in the first five months of this year, currently trading at $1 to GH₵10.30. That’s the strongest level the cedi has reached in over two years, and the sharpest appreciation over this period since 2010.

This very impressive run, which doesn’t look like it’s ending soon, has triggered exuberant calls for the cedi to reach parity with the dollar i.e. $1 to GH₵1.

Even President Mahama has waded in, stating:

“I don’t envisage that the currency will come down to sell at GH₵1 to $1. No, that’s extreme. It will collapse our export sector”

He is right.

Before examining why $1 to GH₵1 is both improbable and economically detrimental, see this simple breakdown from JoyNews Research on what’s driving the cedi’s current strength:

The Dollar Has to Come From Somewhere

A stable exchange rate depends on a steady supply of dollars to meet domestic demand. If $1 were to equal GH₵1, it implies that every Ghanaian holding one cedi should be able to obtain one dollar.

But Ghana doesn’t print dollars. The primary ways dollars enter the economy are through exports, remittances, foreign investment, and any U.S.-based returns on Ghanaian assets.

Exports are the largest source of foreign exchange. But more than 80% of Ghana’s exports—gold, cocoa, crude oil—are commodities.

This makes dollar inflows highly sensitive to price swings and production shocks. When prices or volumes fall, so does dollar supply, driving the exchange rate higher.

Put simply, $1 to GH₵1 is not feasible because Ghana does not consistently earn enough dollars to support such a rate unless there is a radical transformation in production and export dynamics.

Even If We Could, Should We?

Assume, implausibly, that Ghana did earn enough dollars to hold the rate at $1 to GH₵1. That strength would make Ghanaian goods far more expensive globally, hurting exports.

A strong cedi would undercut the very export revenues needed to maintain the exchange rate.

But it wouldn’t stop there. Import duties, one of the country’s key revenue sources, would also take a direct hit.

These currently bring in about GH₵18 billion annually, and government projections target GH₵26 billion. If the dollar traded at GH₵1, those revenues would be slashed dramatically, blowing a hole in the fiscal framework.

This is exactly why China, despite its vast reserves and consistent trade surpluses, keeps the Chinese yuan weak: a cheaper currency boosts competitiveness and protects export and tax revenues alike.

Capital Controls and Credibility Risks

To stabilise such a rate, Ghana would likely need to impose capital controls, especially on outflows, to avoid a sudden drain of dollars.

But this would spook investors and multinationals who expect to move capital freely.

Earlier this year, false rumours that the Bank of Ghana was restricting physical dollar withdrawals from foreign currency accounts caused market panic.

Any firm capital control regime would multiply those effects and erode investor confidence.

And even if Ghana somehow hit GH₵1, the central bank likely wouldn’t allow it to stay there.

As the President bluntly put it:

“If the exchange rate goes below a certain floor, I'm sure the Bank of Ghana will make an intervention to make sure that it remains within a certain band that gives the true value of the cedi.”

Bottom Line

For $1 to equal GH₵1, Ghana would need sustained, large-scale dollar inflows.

Given the structure of Ghana’s export economy and industrial base, that is unlikely. Worse, a $1 to GH₵1 would make Ghana’s exports uncompetitive—just as China keeps its currency weak to preserve trade advantages.

Developing Ghana’s capital markets to attract more foreign investment is one path, but even that would require deep reforms and long-term credibility.

And if Ghana somehow managed to reach GH₵1, maintaining that level without introducing capital controls would be near impossible, and those same controls would damage the very confidence needed to sustain the rate.

Ultimately, reaching and maintaining a $1 to GH₵1 rate would require not just structural transformation, but geopolitical leverage and a substantially weaker U.S. dollar.

In short, don’t count on it.

Latest Stories

-

NDC condemns vote-buying in Ayawaso East primaries, launches investigation

7 minutes -

Ayawaso East NDC primary: Sorting and counting underway after voting ends

38 minutes -

Africa must build its own table, not remain on the menu — Ace Anan Ankomah

54 minutes -

US wants Russia and Ukraine to end war by June, says Zelensky

54 minutes -

Let’s not politicise inflation – Kwadwo Poku urges NDC

1 hour -

(Ace Ankomah) At our own table, with our own menu: Africa’s moment of reckoning – again

1 hour -

Land dispute sparks clash in Kpandai; 3 motorbikes burnt

1 hour -

15 injured as Ford Transit overturns at Gomoa Onyaazde

1 hour -

Government pays School Feeding caterers 2025/26 first term feeding grant

2 hours -

Mz Nana, other gospel artistes lead worship at celebration of life for Eno Baatanpa Foundation CEO

3 hours -

Ayawaso East NDC Primary: Baba Jamal campaign distributes TV sets, food to delegates

4 hours -

MzNana & Obaapa Christy unite on soul-stirring gospel anthem Ahoto’

4 hours -

Ayawaso East: 5 vie for NDC ticket for March 3 by-election

4 hours -

Loyalty is everything in politics; Bawumia must decide on Afenyo-Markin – Adom-Otchere

4 hours -

Ghana positions itself as a Competitive Fund Domiciliation Hub

5 hours