Audio By Carbonatix

The world is moving fast towards clean energy. Solar panels on rooftops, wind turbines along coastlines, hydro dams powering cities, and bioenergy fuelling industry are no longer distant ideas; they are becoming everyday realities.

Global agencies believe that by 2050, as much as 90 per cent of electricity could come from renewable sources. But behind this green revolution lies a less visible story: the minerals that make it possible. Rare-earth elements, or REEs, are the quiet drivers of the energy transition.

These minerals are essential. They sit inside the magnets of wind turbines, the batteries of electric cars, and the circuits of our smartphones. Without them, the dream of net-zero carbon emissions would stall. Deposits of rare earths are scattered across the globe, from China and the United States to Australia, Russia, Canada, India, South Africa, and Southeast Asia. The most common minerals mined include bastnäsite, monazite, loparite, and lateritic clays.

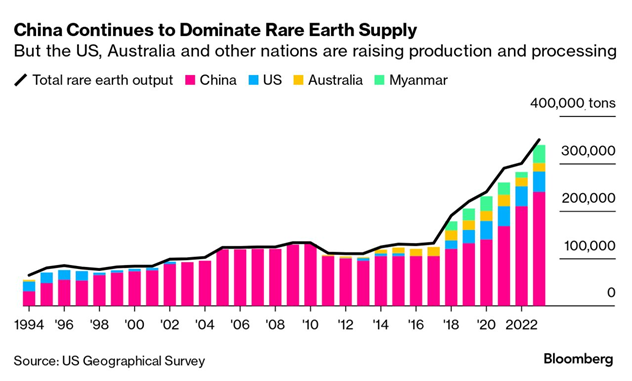

China, however, dominates the industry. It controls nearly 90 per cent of global refining and processing capacity, giving it unmatched power over the mine-to-magnet supply chain. Between 2015 and 2022, rare-earth products generated an estimated USD 123 billion in sales, much of it driven by China’s integrated system. Provinces such as Jiangxi and Sichuan host rich clay deposits that feed this dominance, allowing China to maintain roughly 80 per cent of global output.

For Ghana, the global shift towards an energy transition presents a significant opportunity to position itself economically and take a major step forward. Recent studies have shown that rare-earth element (REE) deposits in Ghana are located within the Dahomeyide suture zone in the south-eastern part of the country.

This zone, formed during the Pan-African Orogeny, is part of the Kpong Complex, which contains deformed alkaline rocks and carbonatites (DARCs). The Dahomeyide Belt is a large geological feature that extends from the Gulf of Guinea coast in south-eastern Ghana, running north-east through Togo and Benin, and into Burkina Faso and Niger.

Within this belt lies the suture zone, where carbonatite occurs within an alkaline complex along the sole thrust of the suture zone. This area is characterised by high concentrations of incompatible trace elements, which host REE-bearing rocks. The suture zone follows a NNE–SSW trend in south-eastern Ghana, stretching from south of Somanya to north-east of Pore.

Geochemical analyses indicate that the rocks of the Kpong Complex originated from mantle-derived magma and exhibit the high-light rare-earth element (LREE) enrichment typical of carbonatites. The Kpong Complex, generally less than 100 metres thick, consists of sheared layers of carbonatite and nepheline gneiss. This geological complex is located near a town on the Volta River in Ghana’s Eastern Region, at approximately 6°10′N, 0°04′E.

Moving forward, other prospective areas that could be explored for these minerals include regions where calcite and dolomite are found in various geological contexts across the country. Northern Ghana hosts substantial sedimentary reserves of both calcitic limestone (approximately 15 million tonnes) and dolomite (approximately 20–30 million tonnes) located within the Voltaian Basin around Bongo-Da, Nalerigu, Daboya, and Buipe. South-western and central Ghana also include a large limestone ridge near Nauli in the Western Region (over 23 million tonnes).

Most of the rare-earth element occurrences identified along Ghana’s coastline are likely secondary in nature, formed through the erosion and transport of REE-bearing minerals from upstream bedrock sources into coastal and near-shore environments.

Heavy minerals such as monazite, zircon, rutile, and ilmenite found in beach sands are typically derived from inland source rocks and concentrated by wave and current action along the coast. This suggests that the coastal deposits themselves may act as geochemical and mineralogical indicators rather than primary sources.

With strategic geological exploration that focuses on tracing these heavy-mineral assemblages upstream through sediment provenance studies, drainage geochemistry, and targeted bedrock mapping, it becomes possible to identify inland source areas that may host more significant or primary REE mineralisation. Such an approach provides a cost-effective pathway for narrowing exploration targets and improving the chances of discovering economically viable REE deposits in Ghana.

Rare earths are becoming the new oil of the green economy. For Ghana, the sands and rocks along its coasts may hold more than minerals; they may hold the key to powering tomorrow’s world.

Latest Stories

-

Unlicensed betting firms face sponsorship ban

55 minutes -

Police investigate ‘abhorrent’ racist abuse of players

1 hour -

FIFA wants injured players to stay off for one minute

1 hour -

Pacquiao and Mayweather agree professional rematch

1 hour -

Ghana intensifies U.S. investment drive with strategic California outreach

2 hours -

UK says ‘nothing is off the table’ in response to US tariffs

2 hours -

Netflix boss defends bid for Warner Bros as Paramount deadline looms

3 hours -

One Man, One Woman or Polygamy?

3 hours -

‘The end of Xbox’: fans split as AI exec takes over Microsoft’s top gaming role

3 hours -

Carney heading on trade trip as Canada seeks to reduce reliance on US

3 hours -

Trump threatens countries that ‘play games’ with existing trade deals

3 hours -

A Plus seals three-year partnership with MGL for Gomoa Easter Carnival

4 hours -

Parliament to probe SHS sports violence; sanctions to apply – Ntim Fordjour

5 hours -

Upholding parental choice and respecting the ethos of faith-based schools in Ghana

5 hours -

SHS assault: Produce students in 24 hours or we’ll storm your school – CID boss to SWESBUS Headmaster

5 hours