Two Ghanian pensioners are discussing how they first met, almost 60 years ago, in London’s Soho jazz scene. Teddy Osei, a saxophonist and drummer, and Lord Eric Sugumugu, a percussionist, forged a friendship “playing among the diaspora”.

Sugumugu had a gig with Ginger Johnson and His African Messengers, while Osei played with Dudu Pukwana, the great South African jazz saxophonist.

Sugumugu is ebullient, leaping out of his seat to exclaim about their role in making the 60s swing: among many other things, he was part of an African drum troupe the Rolling Stones employed at their 1969 Hyde Park concert.

Although Osei wasn’t there himself, he did join the Stones to perform Brown Sugar on Top of the Pops.

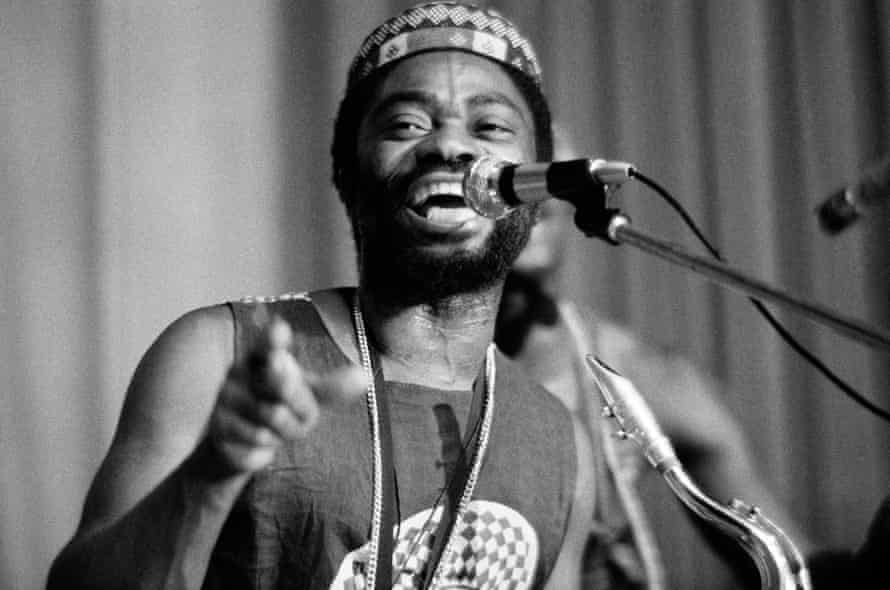

Osei, aged 87, is a stroke survivor, his voice rarely rising above a whisper. But with a new album out, he wants to tell his story as an unsung pioneer: as founder and leader of the band Osibisa. Best known for their two mid-70s hits Sunshine Day and Dance the Body Music,

Osibisa never conformed to genre, mixing Ghanian highlife music with jazz, soul and rock, and later funk and disco. This hybrid music, drawing from across the diaspora, is exactly what you hear in today’s young Black British stars performing drill, Afro-swing and Afrobeats.

Osei nods in agreement at the suggestion his sound was prescient. “I was born in Kumasi, Ghana’s second city, and played highlife with my band the Comets in the 1950s. I shifted to Accra but I wanted to go abroad.” He travelled to London in 1962.

“I got work in a hotel, washing dishes, and enrolled in evening classes. I played jazz and rock’n’roll, often working with my fellow Africans – we were one community. Back then, there were very few Africans in London. Now it’s full up!” He laughs, then adds: “But it’s good they all got a chance to come here.”

Leading Cat’s Paw, soul music covers band, Osei worked across Europe until, after an extended sojourn playing Tunisian hotels, he returned to London in 1969 determined to form Osibisa. Their name derived from osibisaba, a prewar proto-highlife rhythm. Two of his original bandmates were friends from Ghana, another two were Nigerian.

“I wanted to make a difference to the African music scene,” says Osei. “I wanted to make a different sound.” Initially so poor the band were forced to rehearse in Osei’s Finsbury Park basement flat, it was when three Caribbean musicians joined that Osibisa found their sound. “Wendell Richardson could play rock guitar,” explains Osei.

Osibisa quickly made a mark, their dynamic fusion allowing them to play the Roundhouse and Ronnie Scott’s alongside African and Caribbean haunts. Jimi Hendrix dropped in to see them rehearse: “He loved our rhythms.

If he’d played with us, he would have lived.” But it was Stevie Wonder who, while in London in 1970, was so enamored by Osibisa he joined them on stage on drums, then helped engineer a record deal.

Stevie Wonder was so enamoured by Osibisa he joined them on stage on drums, then helped them get a record deal

They were managed by Gerry and Lilian Bron, industry veterans who had previously managed the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. It was they, says Osei, who insisted on Tony Visconti producing Osibisa and Roger Dean designing their LP covers. (Dean later crafted fantastical visions for Yes.)

Was it a culture clash, Visconti and Dean being associated with British rock bands? No, says Osei, both men listened to him. “Visconti was leaning on me for suggestions as to how to get the right sound – I love him for that! And Dean asked what kind of ideas I had.

I said, ‘Something African’ and suggested an elephant. He drew a flying elephant and it’s been Osibisa’s logo ever since.”

The band’s eponymous debut album and follow-up Woyaya, both 1971, were Visconti/Dean efforts that sold strongly internationally and are now regarded as their finest work.

Music for Gong Gong, from their debut, quickly became a soul DJ favourite (Louie Vega has remixed it), while a moving interpretation of Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s Spirits Up Above is one of Woyaya’s highlights. I mention this and Osei replies: “Roland Kirk, he jam with us in London.”

Seeing I’m impressed, Osei says Osibisa also played with Sun Ra when the maverick American made his UK debut in 1971. Sugumugu then describes his Belsize Park African music club Iroko – where the Osibisa/Kirk jam took place – as “the place where all Black musicians visiting London headed to. Fela came there!”

The Nigerian star Fela Kuti is now seen as the pioneer of Afrobeat, but Osei and Sugumugu want to make something clear. “Fela got all his vibes from Ghana,” says Osei. “That’s where he got his rhythms. He then did everything his way – no one could tell him anything. He was a character.”

“Without Osibisa,” adds Sugumugu, “Fela wouldn’t have happened. He had his own beautiful madness.”

Osibisa were the first African band to command an international audience, as well as being hugely popular across their home continent. But, as they developed a pop sound in the mid-70s, the likes of Kuti and King Sunny Ade became the dominant figureheads for a new wave of African roots music that would capture international attention in the 80s.

“Fela was very friendly to me, maybe because we both play keyboards,” says Robert Bailey, a co-founder of Osibisa, who remains in the band.

“The first time we met him in Lagos, I remember he was so pleased to see all of us.” Bailey was only 19 when he joined, finding “the music fascinating. It was very familiar to me with all the rhythms that I had played and listened to in Trinidad.” Not only did the eight musicians bond but, he says, audiences also responded immediately.

“The ethos was happy music and good vibes. We got on to the student union circuit and shared the bill with many rock groups – Black Sabbath, Jethro Tull – which was a great experience. I was amazed how fast it all happened. We then toured for four years with an occasional week off. It was fine for a while, but it became exhausting.”

So much so that Bailey first left the band in 1975: Osibisa’s revolving-door policy has seen band members coming and going over the decades.

“Teddy’s always been very calm,” says Bailey, “so there has never been any bad blood between us. I’ve taken time out to work as an arranger and bandleader but I love to return to Osibisa. It’s something special – this African and Caribbean music made in London.”

Is it true, I ask, that marijuana played a big part in Osibisa’s sound? “Oh, yeah,” replies Bailey with a laugh. “It’s a spiritual drug and we were heavy smokers.”

After releasing 1977’s Black Magic Night: Live at the Royal Festival Hall, Osibisa concentrated on touring, commanding huge audiences across Africa, India (100,000 people attended one concert in Kolkata) and Latin America.

Ghanaian guitarist Kari Bannerman joined after Wendell Richardson was drafted into Free, and recalls his first tour with the band being in Thailand. Then they played in Lebanon – “the Israelis had bombed the airport the day we arrived” – and Syria. “People all over the world loved the vitality and spontaneity of the music,” says Bannerman.

Indeed, seeing them at the London Barbican in 2015, I was struck by their musical ebullience. That year, Osei also suffered a stroke that stopped him from touring, but at 87 he still calls the shots: while he doesn’t play on New Dawn, Osibisa’s first studio album in 12 years, Osei signed off everything from the songs to the sleeve design.

I suggest that contemporary African pop stars Burna Boy and Fuse ODG are Osibisa’s sonic offspring but the veteran jazzman appears bemused by my suggestion. “They talk,” he says. “Not so much singing and playing.” Sugumugu, not about to let the moment pass, declares: “Yesterday I listened to Afrobeats on Kiss FM – and they all come from Osibisa!”

What is he most proud of? “Osibisa,” he says, “brought Black people together in America, the Caribbean and Africa. Osibisa gave Africans confidence in their own music.”

Latest Stories

-

Paris 2024: Opening ceremony showcases grandiose celebration of French culture and diversity

3 hours -

Spectacular photos from the Paris 2024 opening ceremony

4 hours -

How decline of Indian vultures led to 500,000 human deaths

4 hours -

Paris 2024: Ghana rocks ‘fabulous fugu’ at olympics opening ceremony

4 hours -

Trust Hospital faces financial strain with rising debt levels – Auditor-General’s report

5 hours -

Electrochem lease: Allocate portions of land to Songor people – Resident demand

5 hours -

82 widows receive financial aid from Chayil Foundation

5 hours -

The silent struggles: Female journalists grapple with Ghana’s high cost of living

5 hours -

BoG yet to make any payment to Service Ghana Auto Group

5 hours -

‘Crushed Young’: The Multimedia Group, JL Properties surprise accident victim’s family with fully-furnished apartment

6 hours -

Asante Kotoko needs structure that would outlive any administration – Opoku Nti

7 hours -

JoyNews exposé on Customs officials demanding bribes airs on July 29

7 hours -

JoyNews Impact Maker Awardee ships first consignment of honey from Kwahu Afram Plains

8 hours -

Joint committee under fire over report on salt mining lease granted Electrochem

8 hours -

Life Lounge with Edem Knight-Tay: Don’t be beaten the third time

8 hours