Audio By Carbonatix

Abstract

Energy infrastructure underpins modern society, yet Africa faces a critical trade-off between immediate survival needs and long-term sustainability. This article examines the global and African energy landscapes and seeks to measure the trade-offs between survival and sustainability to close the energy gap in Africa. Additionally, it highlights renewable projects and proposes pathways to bridge the energy gap while aligning with global goals.

Introduction

Energy infrastructure is the fundamental pillar of modern society, fuelling vital systems from homes and businesses to industries and transportation. More than 620 exajoules (EJ) of energy were consumed globally in 2023 across sectors from both renewable and non-renewable sources[1]. Renewable energy focuses on generating eco-friendly power from natural sources, in contrast to non-renewable sources, which have negative environmental impacts.

Non-renewable sources, including coal, oil, and petroleum products, prioritise efficiency and cost-effectiveness at the expense of the environment. Oil and gas production, processing, and transport account for 5.1 billion tonnes of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—approximately 15% of energy-related GHG emissions worldwide.[2] Although fossil fuels have been the primary energy source for centuries, both advanced and emerging economies are improving their energy mixes.

Recent developments, such as species extinction, changing rainfall patterns, droughts, food crises, rising global temperatures, and rising sea levels, underscore the urgency for a faster transition to cleaner, and sustainable energy sources.

Article 2 of the Paris Agreement aims to keep global temperatures below 1.5°C in the long term, with measures to reduce the risks and impacts of climate change and to boost renewable energy. Developed economies have pledged aid to support developing nations' transitions, but implementation has been limited, shifting the focus to resilience and economic management. With aid constrained, the future of sustainable energy remains uncertain.

This article explores ways of powering Africa’s renewable energy future, while considering the trade-offs between survival and sustainability in closing Africa's energy gap.

The Global Energy Case

Global energy demand grew by 49% between 2000 and 2023, with a 1.8% uptick in 2024—the highest since 2021's pandemic recovery.[3] The energy landscape has transformed, with clean energy production doubling alongside fossil fuels, driven by wind and solar surges. Despite economic growth, energy supply lags demand. According to the Energy Institute, in 2023, world energy production was around 617 EJ, with consumption at 620 EJ. This deficit demands investments, but rising costs intensify the survival-sustainability trade-off, including in Africa.

The Energy Case of Africa

Africa, the second-fastest-growing region after Asia, has a Gross domestic product (GDP) of ~ US$2.8 trillion and 3.7% real growth[1]. Rich in resources, it balances present needs with future sustainability. The continent holds 125 billion barrels of proven oil reserves (7.2% of global) and 620 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (7.5% of global), with 84% of pre-production gas reserves. Renewable potential includes 10 terawatts (TW) of solar, 110 gigawatts (GW) of wind, 35 GW of hydro, and 15 GW of geothermal, which together account for 60% of global supply.[2] Yet, this potential remains untapped due to poverty, limited investments, outdated infrastructure, and governance issues.

The trade-offs between renewables and fossils involve balancing reliability and convenience versus sustainability, where fossils offer consistent power but drive climate change, while renewables (solar/wind) are clean but intermittent, requiring storage/grid upgrades, and both have resource demands (minerals for renewables, water/land for fossils) and economic impacts (jobs, costs, subsidies) that shift over time, with renewables gaining long-term economic and environmental benefits despite upfront investment challenges.

Africa faces a major trade-off: huge renewable potential versus reliance on fossil fuels, where high upfront costs, financing gaps, and existing infrastructure favour fossil fuels, but where renewables offer better long-term opportunities, including jobs, climate benefits, and energy independence.

Africa accounts for ~75% (600 million) of the world's 800 million population without access to electricity. Although grid/mini-grid connections rose by 11% in 2024, the pace of growth is insufficient to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 - affordable and clean energy for all[3] and Goal 7 of the Africa Union (AU) Agenda 2063 - environmentally sustainable and climate resilient economies and communities. The following highlights show some developments across Africa:

Northern Africa: According to IEA, for more than 10 years, the renewable energy production in Northern Africa has increased by 40%. Morocco has demonstrated significant strides in transitioning from coal to renewables and gas, aiming for a lower-carbon energy future, while Egypt has tripled its solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity since 2020[4]. Northern Africa’s abundant wind and solar resources make it an ideal location for clean energy production, with potential for green hydrogen export to the European Union.

Southern Africa: Mozambique has the greatest power generation potential in Southern Africa, with the potential to generate over 180 GW once all potential resources are fully utilised[5]. Currently, due to lack of investments the country is struggling to meet its power potential leaving less than 50% of the population without access to electricity. Just like Mozambique, South Africa also faces blackouts and load shedding, losing approximately 481-billion-rand (US$ 26.7 billion) in productivity[6].

Eastern Africa: Growth in Eastern Africa is driven by gas development and liquified natural gas (LNG) exports and the region is expected to become a global player in the energy sector. Tanzania is developing a 10 million tonnes per annum LNG project, worth US$ 30 billion,[7] while Uganda is set to launch its oil export pipeline project in 2026 and make earnings by 2027 via the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).

Western Africa: Nigeria produces about 5,801 megawatts (MW) of electricity at its peak[1] which has led to inadequate capacity, causing 6.6 hours of blackouts, daily.[2] Additionally, 32% of the country’s energy mix is generated from oil-based plants[3]. On the other hand, Ghana improved in its power supply with the acquisition of the 250 MW Ameri power plant but relies on fossils to generate power. There is a planned Petroleum Hub project in the Western region of Ghana, which could transform the country into a regional centre for petroleum trading and logistics. Additionally, the country’s recent established private refinery should reduce its import dependence, significantly[4].

Central Africa: Angola, the second-largest oil producer in Africa, dominates the Central African energy sector which is investing fossil fuel revenues into renewable energy and hydro power expansion. Within the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) sub-region, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon supply nearly 85% of the natural gas output, which reached 6.94 million tons in 2025.[5]

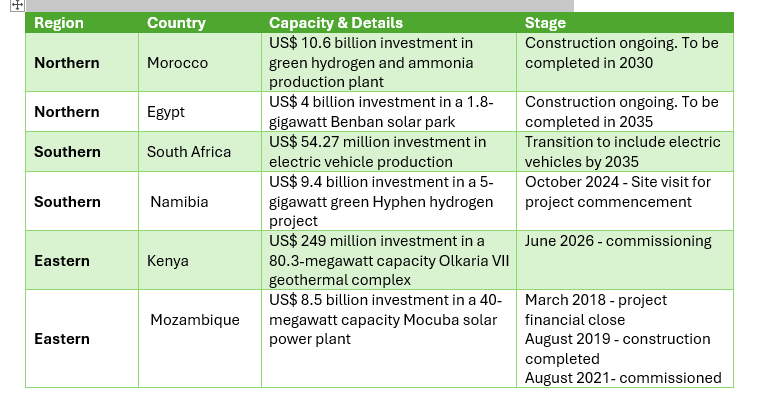

Renewable Energy Projects in Africa

Africa’s energy landscape is undergoing a transformative shift, as numerous countries on the continent increasingly prioritise investments in clean energy, driven by competitive financing options and a growing focus on sustainability. In 2024, sustainable debt in Africa hit a US$ 13 billion record.[6] Notably, from the 2025 Annual Report by Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), thirteen guarantees have been issued by the World Bank Group's MIGA, with about US$ 489 million expected to fund climate projects.[7] Over US$ 200 billion will need to be invested annually to meet Africa's energy and climate-related targets by 2030. [8]

Morocco World News, Total Energies, African Development Bank Group, Africa Energy Portal, Energy Capital & Power, The Emerging Africa & Asia Infrastructure Fund, RePower

Global Trade Tensions

The escalating trade tensions between the U.S. and the rest of the world will have a negative impact on Africa’s oil and gas industry due to the price volatility, which strains budgets and growth.

Trade tensions arising from conflicts in the Middle East (such as Israel-Iran) may exacerbate the disruption and affect prices. Oil prices are capped at US$80 a barrel. For most major African oil producers, such as Nigeria, Angola, Libya, and Algeria, that rely heavily on oil revenues to fund their national budgets, this sustained cap can lead to significant revenue shortfalls, impacting their ability to fund public services and development projects. This could result in a decline in foreign reserves and pressure to devalue national currencies.

The possible Iranian blockade of the world's oil corridor, the Strait of Hormuz, could push oil markets into uncharted territory, as in 2024, oil flows through the Straits averaged 20 million barrels per day, representing about 20% of the world's consumption of petroleum liquids.[1]

Tariffs imposed by the U.S. and Europe on Chinese goods make essential components such as solar panels and batteries more expensive across global markets. This directly translates into higher costs for renewable energy projects in Africa, since it relies heavily on imported technologies from China. As a result, clean energy projects become less financially viable, slowing the pace of installation and expansion. Higher costs for renewable technologies make them less competitive compared to the traditional, and often heavily subsidised, fossil fuels. This encourages some African governments and international investors to increase investments in fossil fuel exploration and production, risking a "lock-in effect" to carbon-intensive pathways.

Opportunities in Critical Minerals and Financing

Natural gas can serve as a vital bridge fuel, complementing the deployment of low-emission technologies and Africa's transition to renewable energy. Africa boasts of more than 620 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves (8.5% of global reserves).[1] Natural gas is also important for producing nitrogen fertilisers, both as a source and as a direct input. Gas-fired electricity could be used as a backup for solar and wind energy. In industrial processes such as steel and aluminium smelting, gas is used to produce fewer emissions than coal.

The governments of the Gulf States and their sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are active investors in Africa, with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) committing to co-finance the US$25 billion African-Atlantic gas pipeline from Nigeria to Morocco, along with the European Investment Bank, the Islamic Development Bank, and the OPEC Fund.[2]

Way Forward

Africa's way forward to achieving SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy for all) and Goal 7 of the AU Agenda 2063 (environmentally sustainable and climate resilient economies and communities) lies not in choosing either survival or sustainability, but in harnessing innovative finance, business models, and local strategies that serve both immediate energy access and long-term sustainable climate objectives.

Innovative financing is key for developers and investors navigating this complex energy landscape and closing the financing gap for clean energy projects in Africa. Blended finance, a key type of innovative financing, is required for de-risking projects. Developers should actively seek partnerships with institutions such as MIGA or the International Finance Corporation to provide credit enhancements that make projects acceptable to risk-averse commercial lenders. Innovative financing also includes sustainable financial instruments such as green, social and sustainability bonds and loans, which can help African countries to bridge the financing gaps that exist in their respective regions. With innovative financing, African nations can get access to investments to realise their power potential for short-term energy needs and at the same time, invest in long-term sustainable, cleaner energy projects.

African governments should set renewable energy targets and modernise infrastructure, for instance, the clean cooking sector needs business models (eg, pay-as-you-go) that treat households as consumers, not beneficiaries. It appears this has proven successful in solar home systems and could be adapted to distribute and finance improved cookstoves. Additionally, governments in various African regions should quadruple solar and wind output, along with grid upgrades to balance survival and sustainability. In terms of local strategies, while long-term sustainability is the destination, short-to medium-term energy strategies should prioritise reliability, affordability, and access. For example, natural gas can play a catalytic role.

Tariffs imposed by the U.S. and Europe on Chinese goods make essential components such as solar panels and batteries more expensive across global markets. This directly translates into higher costs for renewable energy projects in Africa, since it relies heavily on imported technologies from China. As a result, clean energy projects become less financially viable, slowing the pace of installation and expansion. Higher costs for renewable technologies make them less competitive compared to the traditional, and often heavily subsidised, fossil fuels. This encourages some African governments and international investors to increase investments in fossil fuel exploration and production, risking a "lock-in effect" to carbon-intensive pathways.

Opportunities in Critical Minerals and Financing

Natural gas can serve as a vital bridge fuel, complementing the deployment of low-emission technologies and Africa's transition to renewable energy. Africa boasts of more than 620 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves (8.5% of global reserves).[1] Natural gas is also important for producing nitrogen fertilisers, both as a source and as a direct input. Gas-fired electricity could be used as a backup for solar and wind energy. In industrial processes such as steel and aluminium smelting, gas is used to produce fewer emissions than coal.

The governments of the Gulf States and their sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are active investors in Africa, with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) committing to co-finance the US$25 billion African-Atlantic gas pipeline from Nigeria to Morocco, along with the European Investment Bank, the Islamic Development Bank, and the OPEC Fund.[2]

Way Forward

Africa's way forward to achieving SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy for all) and Goal 7 of the AU Agenda 2063 (environmentally sustainable and climate resilient economies and communities) lies not in choosing either survival or sustainability, but in harnessing innovative finance, business models, and local strategies that serve both immediate energy access and long-term sustainable climate objectives.

Innovative financing is key for developers and investors navigating this complex energy landscape and closing the financing gap for clean energy projects in Africa. Blended finance, a key type of innovative financing, is required for de-risking projects. Developers should actively seek partnerships with institutions such as MIGA or the International Finance Corporation to provide credit enhancements that make projects acceptable to risk-averse commercial lenders. Innovative financing also includes sustainable financial instruments such as green, social and sustainability bonds and loans, which can help African countries to bridge the financing gaps that exist in their respective regions. With innovative financing, African nations can get access to investments to realise their power potential for short-term energy needs and at the same time, invest in long-term sustainable, cleaner energy projects.

African governments should set renewable energy targets and modernise infrastructure, for instance, the clean cooking sector needs business models (eg, pay-as-you-go) that treat households as consumers, not beneficiaries. It appears this has proven successful in solar home systems and could be adapted to distribute and finance improved cookstoves. Additionally, governments in various African regions should quadruple solar and wind output, along with grid upgrades to balance survival and sustainability. In terms of local strategies, while long-term sustainability is the destination, short-to medium-term energy strategies should prioritise reliability, affordability, and access. For example, natural gas can play a catalytic role.

in displacing more harmful fuels such as biomass and diesel. This can contribute to the stabilisation of grids and support of industrialisation, while renewable energy capacity is scaled up.

Glossary

AU - Africa Union

CEMAC - Central African Economic and Monetary Community

EACOP - East African Crude Oil Pipeline

EJ - Exajoules

GDP - Gross Domestic Product

GHG - Greenhouse Gas

GW - Gigawatts

I&CP – Infrastructure & Capital Projects

IEA - International Energy Agency

LNG - Liquified Natural Gas

MIGA - Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency

MW - Megawatts

PV - Photovoltaic

SDG – Sustainable Development Goal

SWF - Sovereign Wealth Funds

UAE - United Arab Emirates

Latest Stories

-

Barca dominate Levante to claim La Liga top spot

25 minutes -

Managing Man Utd the ‘ultimate role’ – Carrick

38 minutes -

‘Educate yourself and your kids’ – Fofana and Mejbri racially abused

52 minutes -

Vinicius scores but Real Madrid beaten by Osasuna

1 hour -

Arokodare & Mundle latest players to be racially abused

1 hour -

GPL 2025/26: Hohoe United hold Aduana FC in Dormaa

1 hour -

Eze ‘wanted to prove something’ as he torments Spurs again

1 hour -

US ambassador’s Israel comments condemned by Arab and Muslim nations

2 hours -

Man jailed nine months for stealing

2 hours -

Woman found dead at Dzodze, police launch investigation

2 hours -

Group of SHS students allegedly assault night security guard at BESS

2 hours -

Jasikan Circuit Court remands two for conspiracy, trafficking of narcotics

2 hours -

GPL 2025/26: Asante Kotoko beat Young Apostles to go fourth

3 hours -

T-bills auction: Interest rates fell sharply to 6.4%; government exceeds target by 170%

5 hours -

Weak consumption, high unemployment rate pose greater threat to economic recovery – Databank Research

6 hours