After emphatically rejecting the IMF as a source of relief from Ghana’s escalating economic woes, the Ghanaian government stunned observers with its abrupt announcement of a U-turn.

It is not just that the Ghanaian authorities were disinterested in an IMF solution, they invested significant amounts of political capital undermining its suitability. They accused the Opposition party of having gone to the IMF in 2015 solely because of “mismanagement”. Today, government spokespersons delight in speculating about the big bucks about to flow from the IMF’s gilded funnels. And the even bigger bucks the IMF imprimatur would unlock in the more lavish capital markets.

Ghana has currently borrowed up to 182.5% of its quota from the IMF. Its room for additional borrowing in normal circumstances is thus about 250% of its quota. But it wouldn’t normally be allowed to borrow more than 145% of its quota at one go under the ECF/EFF/SBA arrangements that it has been eligible for throughout its history with the Fund. In dollar terms, it means that Ghana would ordinarily expect not to be allowed to borrow more than $1.45 billion at any one moment.

Ghana’s eligibility for $1.45 billion (or even more at the discretion of the IMF Board) compared to the $918 million received in 2015 is due to the doubling of the country’s IMF quota since then as a result of an expanded economy. The Ghanaian authorities have hinted at an interest in securing even more because in 2015 the country obtained 180% (instead of 145%) of its quota. The same quota multiple as was used in 2015 will entitle Ghana to some $1.926 billion of IMF money.

As my remarks below will attest these are significant sums in Ghana’s current conditions. But just a short while ago, some Ghanaian pundits and ruling party affiliates were calling such amounts, “peanuts”.

It would have been obvious to the government and the ruling party that embracing the same IMF that they had spent months associating with gloom, doom, shame and insignificance would seriously shake the confidence of even their most ardent supporters in their own grasp of economic policy. So why then did they do it?

The official explanation trotted out by many leading party chiefs and government officials is that up to the time a series of emergency cabinet discussions and meetings took place in late June, no decision had been taken whatsoever to abandon the hardline stance against the IMF in favour of “homegrown” fiscal consolidation policies (such as the 20% “across the board” cut in expenditures) and novel revenue measures (such as the e-Levy).

The Information Minister, in a number of press engagements, told the public that it was during a review of revenue numbers, especially in relation to the underperforming e-Levy, in late June that the IMF decision crystalised. Never mind that for months every serious analyst in Ghana had been branding the e-Levy targets as unrealistic.

In fact, up to a few days until the announcement was made, the government’s posture was that a decision was yet to be taken, with everything hinging on a review of revenue data still flowing in.

A careful analysis of the facts and developments following the downgrade of Ghana’s sovereign ratings in 2021 would show however that this picture of a climactic decision based on sudden and overwhelming data is inaccurate.

As early as late April 2022, the country’s economic managers had become aware that the only serious door still open was the IMF one. The continued downplaying of the IMF, hyping of the e-Levy and trumpeting of a “homegrown” fiscal remediation plan were all in hopes of a miracle. They were spectacles not in service to any carefully laid out policy-based strategies but rather in the forlorn hope of influencing the narrative about Ghana and hopefully triggering some kind of bonanza from some impressionable quarters. IMF inevitability merely prevailed in the end.

The above conclusion stems from an analysis of various factors. Including an evaluation presented below of the only “serious” documents the government has been able to present to Parliament as the fruits of a momentous struggle since September 2021 to access the international loan/capital markets. Let us examine the two documents in turn.

Afreximbank Facility

The pan-African development bank, Afreximbank, announced its “Ukraine Crisis Adjustment Trade Financing Programme for Africa” (UKAFPA) in early April after its board approved the facility on March 31st, 2022. Ethiopia, Nigeria and Ghana were among the earliest countries to express interest and commence engagement.

Given the typical sources of Afreximbank’s funds for these types of facilities, it was obvious from the start that facility managers would seek to align the UKAFPA’s credit and risk management with the yardsticks of the big multilaterals, particularly the IMF and the World Bank.

It is not surprising then that the Ghana – UKAFPA agreement laid before Parliament on 8th June 2022 is replete with caveats indicating clearly that without an IMF deal, consummation is literally impossible. Recall that this was weeks before the official IMF U-turn announcement.

Because the agreement is merely a letter of intent outlining the broad “heads of agreement” on the basis of which an actual agreement could be signed in future for Afreximbank to then attempt to raise “between $500 million and $750 million” for Ghana, it is instructive that the IMF elements are some of the most emphatic terms in the document.

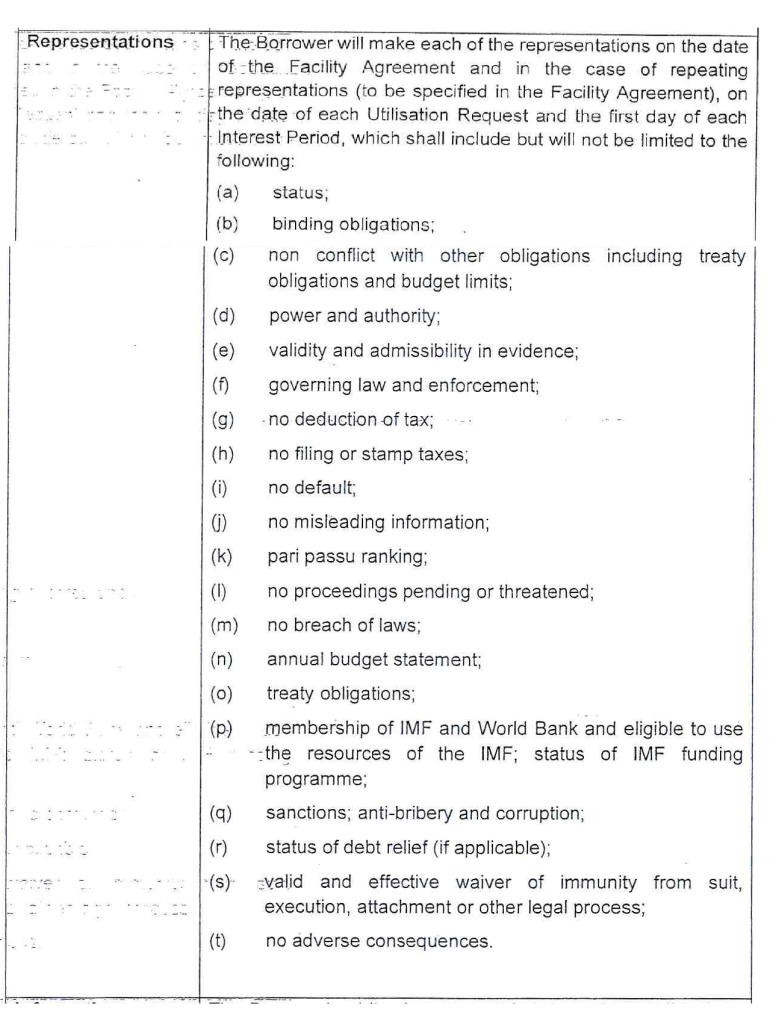

Right from the outset, it is made clear that the agreement entitles Ghana to no assurance of money being raised. Any such raise would be subject to a future agreement following satisfactory due diligence, no deterioration in Ghana’s financial circumstances, and, most important for our discussion here, the receipt of satisfactory documentation.

Regarding the documentary prerequisites, the Agreement anticipates receipt of the government’s Letter of Intent to the IMF within 30 days of submission. Some of the “conditions precedent” give strong hint of the expectation of facility disbursement to align with some kind of multilateral supervision and control regime.

Extract from Ghana – UKAFPA Letter of Intent

A careful analysis of the Afreximbank Letter of Intent submitted for ratification to the Ghanaian Parliament therefore allows no other conclusion except the following:

A. The government had only the most tentative prospect of borrowing internationally in dollars to shore up reserves and, by implication, the local currency (the Cedi). The Letter of Intent had a long list of prerequisites and conditions precedent before a formal agreement could even be reached. Thereafter, everything was dependent on the success of Afreximbank actually being successful in placing the deal. It would be months before any money might arrive at the Bank of Ghana. The impression created in recent weeks of Ghana having viable alternatives to both the Eurobonds market and the IMF in meeting its dollar needs was thus simple acts of image laundering. The only deals in hand were tentative, early-stage, prospects.

B. Even these tentative deals were, carefully analysed, significantly premised on government of Ghana returning to the IMF and observing a supervised fiscal consolidation program.

C. There was no prospect of funds being released in lumpsum as the country has become accustomed with Eurobond placements. The money, if it ever comes, will go to specified projects and will be released based on the satisfactory progress of those projects.

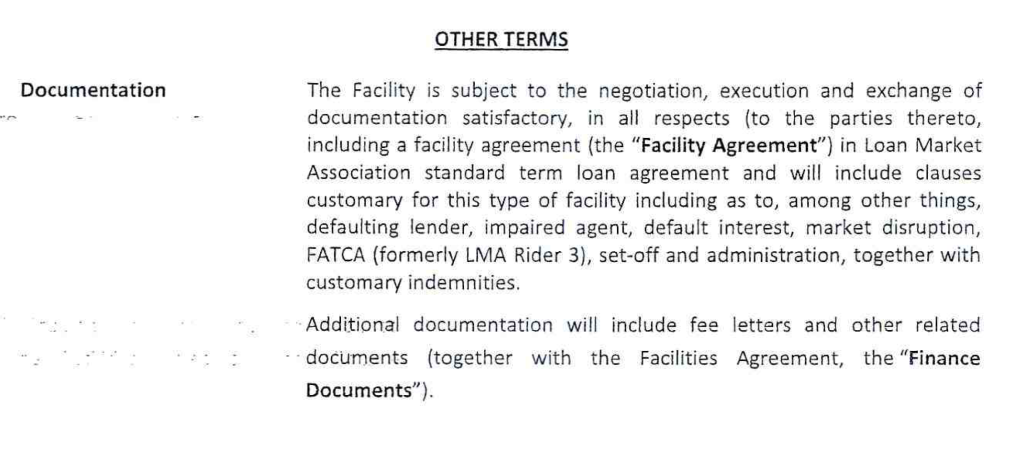

These terms are generally mirrored in the second agreement (also a tentative letter of intent) laid before Parliament outlining broad terms of engagement between the government of Ghana and three banks: Standard Chartered, Standard Bank and Rand Merchant Bank.

Syndicated Loan

The fact that after starting off with a target of $750 million the government eventually had to settle for a $250 million facility, of which only $205 million would actually be disbursed (the rest being swallowed by costs) is itself quite telling.

So dim were the lenders’ view about Ghana’s finances that they demanded insurance. But so serious was the credit risk from the lenders’ point of view that the insurance and reinsurance structuring became protracted, eventually leading to a reduction of the loan amount from $750 million to $250 million.

Here too, the prospective financiers were demanding that government secures ratification of the Mandate Letter in Parliament and meet an extensive list of conditions precedent. Any future facility agreement would also need to be brought to Parliament before the three banks would have the full comfort to raise the $250 million and start disbursing the actual loan amount of $205 million. The funds in this case also will go to specified bankable projects (not to general budgetary support). Once again, it would be months before Ghana sees any money.

The costs of these deals, because of the strict and comprehensive insurance requirement (a sign of how wary the lenders were about Ghana’s finances) added significant cost margins beyond the interest rate. A crude summary is that to borrow just $250 million, Ghana had to be willing to sacrifice $45 million in guarantee costs. This is a country that barely a year ago raised $3 billion at one go with only the bare covenants that apply to all borrowers in the Eurobond market.

Ghana’s Short-Run Crunch

Given the tentative nature of the only loan agreements the government has been able to muster so far and present to Parliament, and notwithstanding reports of officials scouring all over the globe looking for deals, it is pretty clear that hopes of getting significant dollar credit injections into the Ghanaian economy before the end of the year are fading rapidly. The government had to beat a fast retreat to the IMF merely to preserve even these tenuous prospects. That fact raises serious challenges as the IMF process is not much faster than the Afreximbank or the syndicated lending arrangements.

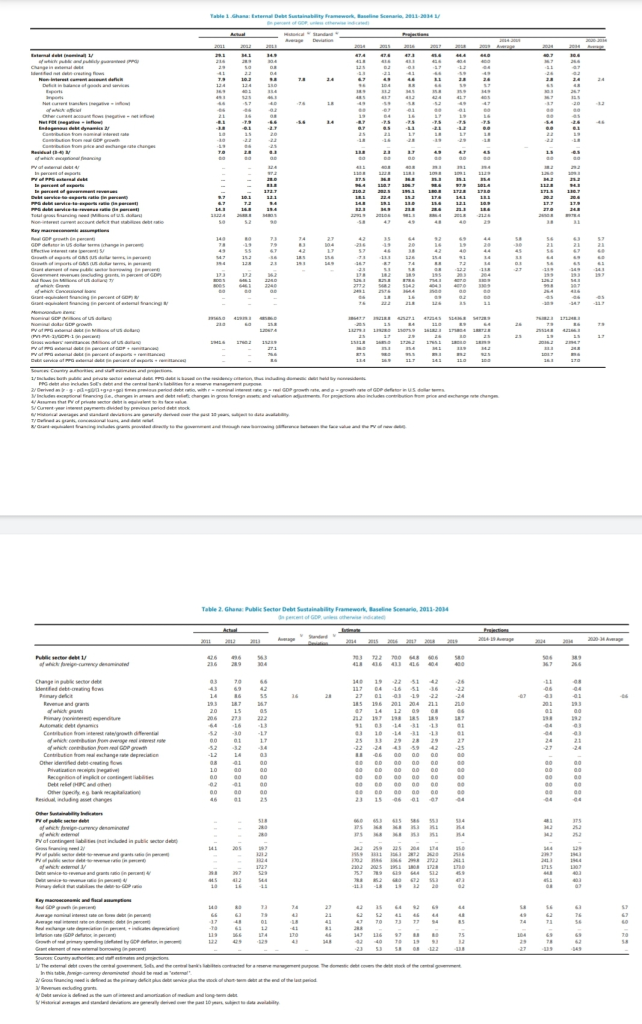

Readers would recall that the last time Ghana did an IMF deal, the process was initiated in August 2014. It was not until April 3rd 2015 that the Board of the IMF finally gave approval. As some analysts have sought to point out, the economic conditions prevailing in 2015 were not as complicated as they are today. Below we reproduce in full the macroeconomic landscape summary table compiled by the IMF around the time of that facility’s approval.

The most important figures to take careful note of are the 2014 and 2015 debt service to revenue ratios. In short, how much of the country’s income was being spent then in paying interest and retiring principal? Versus now. In 2015, less than 35% of revenue went to debt servicing. In 2014, when the approach to the IMF commenced, the figure was just a little above 32%. Today, that number significantly exceeds 60%. In a first quarter of 2022, interest payments alone totaled $1.3 billion (10.6 billion GHS). Properly accounting for amortisation by accommodating the worsening inflation and exchange rate dynamics, would have meant nearly 70% of the 16.7 billion GHS ($2.1 billion) of revenue collected over the period going into debt servicing.

Even worse, the rollover risks of domestic debt have considerably worsened because of the pace at which international investors who not too long ago used to hold nearly 40% of Ghana domestic debt (in 2017) are fast exiting.

Per some projections, foreign holdings of Ghanaian domestic government debt will slump below 10%, having already fallen to around 16% by the end of 2021. When non-resident investors refuse to reinvest their proceeds from prior cycles of investment back into government securities, they typically buy forex and repatriate their money out instead of diverting it into other local investment options. The result is mounting pressure on the Cedi and the risk of government defaults (due to the collapse of the assumption that government won’t have to redeem so much maturing securities at the same time).

These factors, coupled with serious opacity about the true scale of the hidden subsidies and government liabilities in the energy sector, and to some extent the financial sector, have elevated the perception of risks around the government’s finances. Most analysts feel that the situation is even worse than the dire macroeconomic indicators (nearly 30% inflation and a near 30% year-to-date devaluation of the local currency) suggest.

In these circumstances, it could even take the IMF longer to align with government on both a thorough diagnosis of the problem as well as the most effective set of solutions than it did in 2015.

Especially when in previous episodes of this same tango, the government simply refused to follow through with the agreed prescriptions and merely exploited the IMF program to improve its attractiveness to less rigorous lenders and then proceeded to binge heavily on expensive debt. Fearing that the very integrity of the IMF’s programs is at stake, one can only imagine the IMF spending more time trying to design smarter strictures around the government’s capacity to abuse the program. And we are not even factoring into the mix the unresolved issue of whether IMF bailout packages require Parliamentary approval. In 2015, NDC said they didn’t, NPP insisted, quite strenuously, that they did.

So if in relatively less complicated circumstances, it took the government 8 months to clinch a deal in 2014, one would be foolhardy to assume that the economy’s short-run cashflow problems are fixable by a quick IMF program. As we have reminded readers in previous comments, some African countries, like Zambia, have been waiting for an IMF deal for years now.

The current rollover challenges facing the government therefore require a massive and sincere spending review to cut non-critical spending in order to conserve resources to avert a default before a carefully designed debt restructuring of some sort commences next year. Any disorderly strings of defaults in any category of liabilities would only slow down the process of IMF engagement and reduce the overall utility of a program, as indeed we have seen in Pakistan.

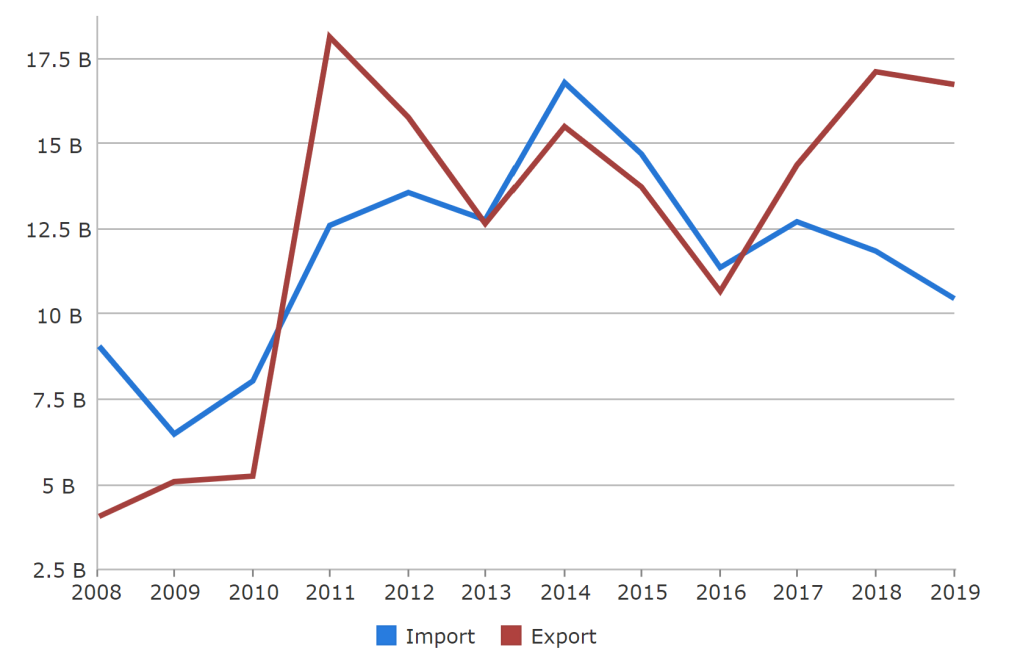

The consistent consigning of the IMF engagement to “balance of payments” support in recent days however underestimates the broader structural issues involved in coming to a consensus on what need to be done. Ghana’s balance of payments situation is complicated by the fact that it is no longer driven primarily by trade. In fact, there is an ongoing imports collapse in the economy due to very high effective tariffs and a slowdown in broader demand. An artificial trade surplus has thus been manifesting for quite some time now.

The current account imbalances confronting the nation are interlinked with persistent fiscal deficits and they both have their roots in three areas other than trade: massive debt servicing costs that can only be addressed by debt restructuring, a large public sector wage bill that can only be tackled through a fundamental redesign of the inchoate welfare state, and structural waste in procurement and capital expenditure born out of political patronage.

The only real room to make a short-to-medium term difference to the country’s dire fiscal plight is in moving aggressively on the third source of the current problem: patronage-driven spending waste. Doing so requires a sincere and independent spending review of recurrent expenditure and planned capital projects heavily tainted by political patronage.

Whether it is the abominable abuse of public funds at the Electoral Commission, the continued pouring of money down the drain through schemes like Kelni GVG or the so-called Smart Workplace project, these leakages are entirely within the control of the political class and frankly, should they go, no one else would miss them.

However, to the extent that politically connected people see benefits in them, they cannot be tackled by routine austerity measures nor is the IMF, in its current incarnation, in light of the collapse of the Washington Consensus, best placed to drive through wide-ranging good governance reforms. Yet, only a genuine commitment by the government to finally confront the structural waste problems will compel it to engage truly independent third parties to conduct the kind of spending review that will take the knife to the pork-barrel mess that procurement and capital project financing have become in Ghana.

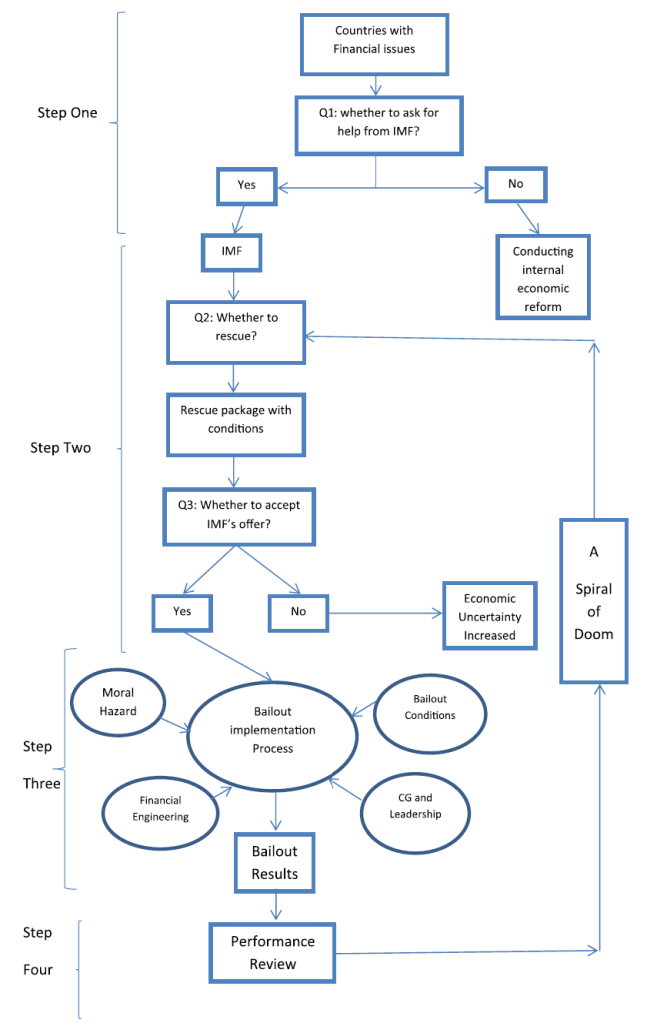

Researchers like Malick Sy and Adela Mcmurray have identified variants of this “good governance enforcement gap” as a contributory factor to their “spiral of doom” analysis of IMF programs that fail to prevent countries from becoming addicted to bailouts.

So, whilst it would seem that the government has already embarked on some austerity measures to achieve a similar outcome to waste reduction, there are serious concerns about the tendency to gut social assistance programs simply because, lacking vested political patrons, they are easy pickings.

For example, there are 3.5 million beneficiaries of the School Feeding Program. Each beneficiary costs the program 12.5 cents a day. There are 185 actual school days in the academic calendar. In short, a seamless School Feeding Program would cost the country just about $81 million a year. Given the full privatisation of the scheme, there are hardly any administrative costs. Yet, the initiative has been saddled with perennial complaints of underfunding for years. This, in a country where the government has very few qualms about throwing away more than $60 million worth of electoral equipment in perfect working condition just to start over again so that crony contracts can be awarded to preferred vendors in flagrant abuse of procurement laws.

Now that it is becoming apparent that neither the IMF nor private lenders will dish out easy money to Ghana between now and the end of the year, the bleak situation the country and its government find themselves in, as they confront the real prospect of technical insolvency in the next couple of months, has been cast in stark relief. Would this rude awakening provide the impetus for reform that previous IMF programs and half-hearted homegrown fiscal consolidation strategies have equally failed to generate?

Will the people rise up to the true measure of citizenship and demand an end to patronage-driven waste? And will the leaders respond?

Latest Stories

-

Let’s live peacefully and shame our saboteurs – Savannah executives of NPP, NDC

3 hours -

Reconstruction of Agona-Nkwanta-Tarkwa road 80 per cent complete

3 hours -

Internet penetration: 10.7 million Ghanaians offline – LONDA Report

3 hours -

USC cancels grad ceremony as campus protests against Israel’s war in Gaza continue

4 hours -

Harvey Weinstein’s 2020 rape conviction overturned in New York

4 hours -

US Supreme Court divided on whether Trump can be prosecuted

4 hours -

There’s enough justification for Affirmative Action Bill to be passed – Minka-Premo

4 hours -

Don’t allow people to manipulate you into vaccine hesitancy – Dr Adipa-Adappoe

4 hours -

Suspend implementation of Planting for Food and Jobs 2.0 for 2024 – Stakeholders

4 hours -

Parkinson’s disease no longer confined to the elderly – Public Health Physician, Dr Momodou Cham warns

4 hours -

Persons living with Parkinson’s disease appeal for support as they face stigmatization

4 hours -

36-year-old-trader sentenced for stealing employer’s money

4 hours -

9 signs you’re falling in love with someone who thoroughly enjoys emotional manipulation

4 hours -

Catholic Diocese of Keta Akatsi hosts Parkinson’s support group meeting

4 hours -

Wa Naa appeals to Akufo-Addo to audit state lands in Wa

5 hours