Audio By Carbonatix

ABSTRACT

This article evaluates the United States Southern District Court of New York’s decision in Aubrey Drake Graham v. UMG Recordings, Inc. and considers its similarities as well as differences in the application of Ghana’s defamation law. It examines the boundary between artistic hyperbole and defamatory assertion, contrasts legal protections in both systems, and discusses implications for Ghana’s developing music economy and disputes arising from public lyrical confrontations among artistes. Utilising a comparative law methodology, this article undertakes a doctrinal analysis of the primary legal instruments governing freedom of artistic expression and reputational harm in Ghana and New York. The analysis reveals a significant divergence in the laws and its application. This comparative assessment of the different legal standards does not merely present a contrast but serves as a catalyst for jurisprudential reflection, challenging prevailing assumptions about free expression and reputation. The analysis is thus targeted at stimulating scholarly discourse and may prove instrumental in spurring specific law review commentary on whether it is necessary to evolveGhana’s defamation framework.

I. INTRODUCTION

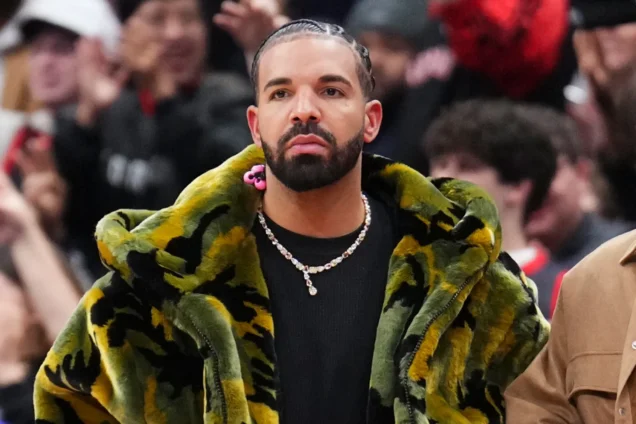

Rap battles have evolved into commercially significant cultural events. They generate audience engagement, streaming revenue, and reputational stakes. The global dispute between Aubrey Drake Graham (Drake) and Kendrick LamarDuckworth (Kendrick) produced allegations of sexual misconduct, domestic abuse, and pedophilia, amongst other things, in lyrical form. Drake sued UMG Recordings Inc. (UMG) alleging that UMG intentionally published and commercially amplified defamatory content made about him by Kendrick in his song “Not Like Us”.

Ghana’s music landscape has, over the years, experienced its fair share of public lyrical rivalries, including the widely publicised tension between “Stonebwoy” and “Shatta Wale” at the 2019 Vodafone Ghana Music Awards ceremony, “Medikal” and Strongman”, “Sarkodie” and “Asem”, just to mention a few. As the Ghana’s industry grows, clarity on the legal limits of artistic provocation remains relevant.

II. THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT: SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK.

Case: Aubrey Drake Graham v. UMG Recordings, Inc

BACKGROUND

Drake, a popular artist collaborated with another artist,Jermaine Lamar Cole (J.Cole) on his album “FOR ALL THE DOGS” and made an assertion in a song titled “First Person Shooter” stating:

“....Love when they argue the hardest MC, is it K-dot, is it Aubrey or me, we the Big 3 like we started a league...”

In March 2024, artists, Metro Boomin and Future released an album, “WE DONT TRUST YOU” which featured Kendrick in the song, “Like That” where Kendrick had this to say in response to J. Cole:

“..F*** sneak dissin first person shooter...Motherf***the big 3 its just big me...”

Insinuating that Kendrick is the only one that is big in the rap at that moment. J. Cole responded in an album “MIGHT DELETE LATER” and in his last song “7 minute drill”, he stated that Kendrick is not as good as he thinks he is and his music is not doing well either. He later apologised and stepped out of the “Battle” leaving Kendrick and Drake to proceed with the feud.

A. FACTS

On April 19, 2024, Drake released a diss track directed at Kendrick and other rappers called “Push Ups”; where he mocked amongst other things Kendrick’s height and shoe sizeand questioned his success, he stated:

“..How the f*** you big steppin with a size-seven men’s on.. pipsqueck, pipe down,... you aint in no big three...Im at the top of the mountain, so you tight now/just to have this talk with your ass, i had to hike down.”

A few days later, Drake released another song titled “Taylor Made Freestyle” which utilized artificially generated voices of rappers, Snoop Dogg and the late 2Pac. This song included encouragement from these rappers urging Kendrick to respond to the diss track Drake had made directed at him.

On April 30, 2024, Kendrick finally responded to Drake in a track titled “Euphoria” where he states that Drake is a manipulator, insults Drake’s fashion sense and taunts Drake for being a coward.

May 3, 2024, had both artists relasing tracks over the course of the day. Starting with Kendrick releasing “6:16 in LA”calling drake a terrible person and accusing Drake of playing dirty with propaganda. Drake reponds by releasing “Family Matters” where he jabs at Kendrick’s relationship with his partner. Almost immediately after, Kendrick released the track ‘Meet the Grahams’ in which he accuses Drake of being a ‘deadbeat’ father and also alleges that Drake has gambling and substance abuse problems. He further insinuates that Drake was a predator.

The next day, May 4 2024, Kendrick released “Not Like Us”, the song which sparked the suit against UMG. In this track Kendrick alleges that Drake is, and associates with pedophiles. The day after, May 5 2024, Drake responded in “The Heart Part 6” denying allegations of pedophilia and stated that he planted some information which Kendrick has used against him.

After what can only be described as one of the most infamous Rap battles in the genre’s history, Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us” emerged as the penultimate of the feud. Drake ultimately sued UMG, which coincidentally both artistshappen to have recording contracts with, alleging defamation, harassment, and unfair business practices. The gravamen of the case of Drake was that UMG had intentionally published and promoted the song, knowing full well that the insinuations contained in the song were false and defamatory. UMG’s legal representation filed a motion to dismiss the suit pursuant to the Federal Civil procedure rules applicable in the USA.

B. ISSUE

In determining the motion to dismiss, the US District Judge Jeanette Vargas, set down as the legal standard for determination; “Whether statements made in a diss track could be reasonably understood as factual assertions capable of sustaining a defamation claim.”

C. HOLDING

The Court granted the motion filed by UMG and dismissed the claim, holding that the lyrics contained in the song constituted a “non-actionable opinion” when understood in their cultural and artistic context and as such no reasonable person would believe such insinuations or take them seriously.

D. LEGAL REASONING

The reasoning of the Judge Vargas may be summed up in the following points;

Under New York law, the elements of defamation are: (1) A defamatory statement; (2) Regarding the plaintiff; (3) Published to a third party; (4) That is false; (5) Made with the applicable level of fault; (6) Causing injury; (7) Not protected by privilege;

The court further defined a defamatory statement as

“one that exposes an individual to public hatred, shame, obloquy, contumely, odium, contempt, ridicule, aversion, ostracism, degradation, or disgrace, or induces an evil opinion of one in the minds of right-thinking persons, and deprives one of confidence and friendly intercourse in society”

The court, in resolving whether “Not Like Us” can reasonably be understood to convey as a matter of fact that Drake is a pedophile or that he has engaged in sexual relations with a minor, stated that the New York Constitution provides for absolute protection of opinions and therefore, the court must determine statements of fact, which are of a defamatory natureand expressions of opinion which are not defamatory and have the protection of the New York Constitution.

Whether a statement made is of fact or is an expression of an opinion is a question of law to be determined by the court based on whether an average person hearing or reading the communication would take it to mean.

The court at page 13 of the judgment in distinguishing between facts and opinions stated the following as the three guiding factors in the court’s consideration: Whether the specific language in issue has a precise meaning which is readily understood, whether the statements are capable of being proven true or false; and whether the full context of the communication in which the statement appears or the broader social context and surrounding circumstances are such as to signal readers or listeners that what is being read or heard is likely to be opinion, not fact.

In applying these factors to the case, the court was of theopinion that the recording is myopically focused on ensuring listeners take one message away, which is that Drake is a pedophile. The statement has a readily understandable meaning, and it is capable of being proven true or false. However, accusations of criminal behaviour are not actionable if, understood in context, and that context is what connotes that they are opinion rather than fact.

The court, in understanding the context in which the statement was made, considered what context means in the circumstances. Context according to the court, includes the forum in which the communication was published, the surrounding circumstances, the tone and language.

The forum: the forum in which a statement is made provides context which can inform the court’s analysis. The forum in this case is a music recording with an accompanying music video and a cover (album) art. The court was of the opinion that diss tracks are “more akin to publications on YouTube and X which encourages a freewheeling, anything goes writing style rather than journalistic reporting which is deemed more factual”. The court concluded that the average listener could not be under the impression that a diss track is a product or some investigation and thereby conveying to the public fact checked and verified content.

Surrounding Circumstances; the fact that the recording was made in the midst of a rap battle means that the audience would not reasonably conclude that those statements constituted assertions of facts when published in a diss track. The statements in “Not Like Us” which was deemed defamatory must not be considered without first looking at the context, which was a rap battle and as such, the court was of the opinion that the publications, whether or not would constitute actionable fact or protected opinion is not based upon the popularity they achieve, and if it was not actionable at the time it was initially produced, then its republication by UMG would not expose them to liability.

Tone and language; the lyrics in the song “Not Like Us” is filled with “profanity, trash-talking and hyperbolic language”which are all indications of opinion which a reasonable listener would not equate to accurate factual reporting. Although an accusation that a person is a pedophile is a serious one, the broader context of a heated rap battle with offensive accusations and provocative language hurled by both parties would not incline a reasonable listener to believe that “Not Like Us” imparts verifiable fact about Drake.

Image and Video; the court was of the opinion that the Imagery or Album art as well as the music video together constitutes an opinion as it shares the overall context as the recording itself.

The court thereby concluded that the diss-track environment signalled rhetorical exaggeration, not factual allegation, that Rap culture anticipates hyperbole and adversarial boasting, that no reasonable listener would treat the lyrics as verified fact that per New York’s constitutional protections treat such speech as opinion and lastly that no private right of action exists for the harassment provision cited.

III. GENERAL LEGAL PRINCIPLES FROM DRAKE V UMG

For the purposes of this article, the following principles are relevant in discussing the juxtaposition of the decision of Judge Vargas to Ghana’s law;

i. Defamation requires a false statement of fact not an opinion.

ii. Context and audience expectations determine whether language implies fact or opinion.

iii. Artistic speech has elevated protection of such publications in U.S. legal jurisprudence.

iv. Music industry “beef” is recognised cultural context in assessing meaning.

IV. GHANAIAN LAW

A. CONSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT

Article 21 of the 1992 Constitution protects freedom of expression, subject to limitations protecting reputation, public order, and morality.

B. DEFAMATION

Post the abolition of criminal libel civil defamation remains actionable. A Plaintiff is required to prove that the publication of words has the potential of lowering reputation in the estimation of right-thinking members of society. Defamation is governed by customary law and the received English common law principles. Modern English defamamtion law consists of two torts, slander and libel. Under common law, there is a distinction between utterances and imputations conveyed in writing, signs or any other means or kind of permanence on statements. In essence, defamation may be actionable in libel without proof of special damage.

However, spoken defamation, libel, is under common law not actionale per se as a tort unless the utterances amount to some other crime like sedition, breach of peace or blasphemy. However, under Ghanaian Customary law, slander is actionable without proof of special damages.

CUSTOMARY LAW

The scope of defamation under customary law is wider than at common law as customary law protects reputation and injured feelings whereas defamation under common law protects reputation only. Customary law does not draw a distinction between libel or slander. In fact, Apaloo J.A. (as he then was) in the case of Anthony v. UCC stated that;

“it is elementary knowledge that while the tort of slander is known to customary law, libel is not, for the very sufficient reason that customary law knows no writing, nor I believe photography”

Libel is said to be unknown to customary law for the simple reason that the writing was unknown to customary law. Slander under customary law is actionable without proof of special damages. It is important to note that truth is not always a defence in customary law slander.

ELEMENTS OF DEFAMATION

Whether the issue before the court is for libel or slander; or it is under customary law or common law, the elements of the tort of defamation are the same and discussed below.

Proof that the communication is capable of a defamatory meaning. In the case of Simpson v. MGN & Anor, Warby Jstated that;

“the natural and ordinary meaning of words for the purposes of a defamation claim is the single meaning that would be conveyed by those words to the ordinary reasonable reader.”

In determining whether a communication is capable of a defamatory meaning, the English Common Law provides four tests namely; (a) that the communication substantially affects in an adverse manner, the attitude of other people towards a person; (b) that the communication was made deliberately or maliciously rendering him ridiculous or tends to hinder mankind from associating or having intercourse with him; (c) that the communication uses words that damage a person in his profession, business, office or trade; and (d) words spoken in the heat of a quarrel or argument are not defamatory.

The interpretation of the words determines whether or not they are defamatory; The words must be construed in their fair and natural meaning as reasonable, ordinary people will understand except where innuendo is pleaded. An innuendo is a defamatory imputation where extrinsic facts, known to the reader or listener, import into words spoken or the statement some secondary meaning, in addition to or alteration their ordinary meaning. Therefore, in a true innuendo, some extrinsic facts must be known to a group, which make the ordinary words defamatory.

Reference: This means there should be reference to the plaintiff or something in the defamatory statement pointing to the plaintiff. Where the plaintiff’s name is not mentioned, there must be evidence connecting the plaintiff to the statement.

Publication: Libel and slander protect reputation, therefore, unless the defamatory matter is published, a person’s reputation suffers nothing and thereby cannot be known as a defamatory matter. Publication is making the defamatory matter known, after it has been written or spoken to some persons other than the person of whom it is written or said.

With defamation, each repetition is a fresh publication, thus giving the plaintiff a cause of action.

UNDERSTANDING THE SCOPE OF SLANDER

Slander under common law requires proof of special damage. This means that a plaintiff can only succeed in an action in slander at common law when he can show that he suffered damage as a result of the slander. There are however four exceptions to this rule.

Imputation of crime; where a person verbally or orally falsely imputes that the plaintiff has committed a crime for which he could be punished corporally, it shall be actionable per se. Where the imputation attracts a fine, it shall not be deemed actionable per se. It is important to note that the imputation need not be an imputation of a specific crime, it is enough, if the words suggest that the plaintiff has committed some crime.

Imputation of a loathesome disease; where a person imputates that a person or the plaintiff is suffering from a veneral disease, the plaintiff is entitled to succeed as this act is deemed actionable per se. Example of such diseases are not expressly stated. However, there can be an implied notion that would show that diseases which are of a contagious and life-threatening condition, the plaintiff may succeed as right thinking members may shun the plaintiff.

Slander in respect of an office, profession and trade; where words are uttered about a person that tends to disparage him or her in his office, profession, trade or business, then those words are actionable per se.

Imputation of unchastity; in the United Kingdom, it is slander to impute unchastity to a woman under the Slander of Women Act,1891. This includes allegations of lesbianism. In Ghana,the law was laid down in Hotchand v. Gentleman Salami (1965) C.C. 187 where Djabanor J. Stated that:

i. Spoken words imputing unchastity to a woman are, under the customary law, actionable per se.

ii. But it is also sound that, if at the time the words were uttered, there were circumstances known to the hearers, which clearly show that the words were not used in the sense of imputing unchastity, then no action lies.

iii. Words like ‘prostitute’, etc. Which plainly impute unchastity cannot be actionable without proof of special damage, if it is clear that they were not intended to impute unchastity, but were spoken merely as quarrel, vituperation or abuse and were so understood by the hearers.

Special damage: this means that the plaintiff has suffered a material loss as a result of the defamation. Material loss is quantified in money or pecuniary loss.

Causation: the test for causation is reasonable foreseeability as in negligence. The concept for foreseeability is narrower.

DEFENCES TO DEFAMATION

Absolute Privilege: this defence covers the occasion or context in which the statement is made, the nature of the communication or the writer, the speaker or the publisher.Although the publication may be defamatory, the freedom of speech in certain circumstances can serve as a complete bar to the action. The four types of communication that is privileged are (a) Executive matters (matters relating to the state is considered privilege. This protectes diplomatic conversations and like communications) (b) Judicial Proceedings (any statements made before the bar or the bench are covered under absolute privilege. (c)Legislative proceedings (parliamentary proceedings are considered privilege such that parliamentarians enjoy immunity from court proceedings for acts, information and speeches made in parliament. (d) solicitor-client communications (communications between a lawyer and their client is covered under absolute privilege.

Qualified privilege: this comes to play where in the discharge of ones private or public duty, a fair statement is made, whether legal or moral, or in the conduct of his own affairs. This is also categorised into five (5) namely: (1) Words relating to matters of common interest, (2) Words protecting the interest of publisher, (3) Words protecting the interest of another, (4) Public interest, (5) Misconduct of a public official

Qualified privilege is destroyed by evidence of malice (improper motive). Qualified privilege will also be defeated by excess of privilege. This happens when the material is circulated beyond persons who should legitimately receive it.In Kojo Tsikata v Newspaper Publishing plc, it was held that inaccuracies will not undermine the protective cover of qualified privilege.

Fair Comment: comments made by people on matters of public interest are such comments being made honestly and without malice. For this defence to succeed, the defendant must satisfy the following conditions: (1) The comment must be on a matter of public interest, (2) The comment must be based on a fact, (3) The comment must be an opinion.

Justification: this defence means that the defendant says the publication is true. The defendant must establish the truth of all the material elements, or that the statement is substantially true. It must be noted that truth or justification is an absolute defence to common law defamation. Under English Defamation Act 1952, where several charges are levelled, proof of some, provided what is left does not materially injure the plaintiff, will be sufficient for purposes of the defence. But it must be noted that nothing stops the plaintiff on relying on the assertions that the defendant cannot establish.

a person who consents to the publication of the defamatory matter cannot succeed in a defamatory action concerning that consented publication.

STATUTORY DEFENCES

According to the second schedule of the Courts Act, 1993(Act 459), English statues shall apply in Ghana as statues of general application. The second schedule (section 119 (1)) states:

Section 119—Application of English Statutes of General Application.

(1) Until provision is made by law in Ghana, the Statutes of England specified in the Second Schedule to this Act shall continue to apply in Ghana as statutes of general application subject to any statute in Ghana.

This provision makes the Libel Act, 1843(6&7 Victoria, c.96) applicable in Ghana. Sections 1 & 2 of the Libel Act,1843 states that

[1.] Offer of an apology admissible in evidence in mitigation of damages.

In any action for defamation it shall be lawful for the defendant (after notice in writing of his intention so to do, duly given to the plaintiff at the time of filing or delivering the plea in such action), to give in evidence, in mitigation of damages, that he made or offered an apology to the plaintiff for such defamation before the commencement of the action, or as soon afterwards as he had an opportunity of doing so, in case the action shall have been commenced before there was an opportunity of making or offering such apology.

[2.] In an action against a newspaper for libel, the defendant may plead that it was inserted without malice and without neglect and may pay money into court as amends.

In an action for libel contained in any public newspaper or other periodical publication it shall be competent to the defendant to plead that such libel was inserted in such newspaper or other periodical publication without actual malice, and without gross negligence, and that before the commencement of the action, or at the earliest opportunity afterwards, he inserted in such newspaper or other periodical publication a full apology for the said libel, or, if the newspaper or periodical publication in which the said libel appeared should be ordinarily published at intervals exceeding one week, had offered to publish the said apology in any newspaper or periodical publication to be selected by the plaintiff in such action; and to such plea to such action it shall be competent to the plaintiff to reply generally, denying the whole of such plea.

This means that a defendant may be allowed at the first opportunity to express remorse and offer amends. If this offer is rejected by the plaintiff, the defendant may refer to it in his or her pleadings. The Act requires that the court considerssuch offers in determining liability.

C. OPINION VS FACT

Ghanaian courts recognise fair comment where opinions are honestly expressed on matters of public interest. However, an allegation implying criminal conduct ordinarily carries a defamatory meaning unless clearly rhetorical or made in the heat of an argument. There is no First Amendment equivalentof protected opinions in Ghana. Artistic speech does not enjoy the same elevated threshold as U.S. jurisprudence.

V. APPLICATION: IF THE CASE OF DRAKE V UMB AROSE IN GHANA.

A Ghanaian court would likely ask:

1. Would the reasonable listener interpret the lyrics as factual criminal allegations?

2. Was the language framed as artistic exaggeration or literal accusation?

3. Did publication by a label materially contribute to reputational harm?

Under our civil procedure, courts are generally slow to terminate civil claims at the pleading stage where the resolution of the dispute depends on contested questions of meaning, context, intention, or factual inference. Applications that seek to strike out pleadings or dismiss actions summarily are granted only in clear cases where the statement of claim discloses no reasonable cause of action or is plainly frivolous, vexatious, or an abuse of process. In defamation actions in particular, the determination of whether words are defamatory, whether they refer to the plaintiff, and how they would be understood by the ordinary reasonable listener are issues that are often fact sensitive and context driven. These matters typically require the court to consider evidence of audience perception, surrounding circumstances, and the manner of publication. Against this procedural background and given Ghana’s strong tradition of protecting reputation coupled with the absence of a constitutional doctrine that accords elevated immunity to artistic speech, a dismissal of a claim of this nature at the pleading stage would be less certain. A Ghanaian court would be more inclined to allow the matter to proceed to trial in order to determine context, meaning, and harm on the evidence.

The reasoning in Banson v Nana provides a vital interpretive bridge for modern questions about defamation in Ghana’s creative industry. Lassey J’s statement that; “mere vituperations cannot constitute slander or defamation” rests on the understanding that not every angry or offensive remark amounts to actionable defamation. The court drew a distinction between impulsive insults uttered in the heat of passion and deliberate statements that impute dishonesty or moral failing in a way that reasonable members of society would interpret as damaging to reputation. The decision confirms a central idea in Ghana’s defamation law: context and intent determine liability. Words spoken in anger may injure feelings, but only those that strike at moral or social standing become legally significant.

This principle, however, becomes complicated when applied to artistic production. The concept of mere vituperation assumes immediacy. It refers to speech that arises spontaneously in a moment of emotion or quarrel. In contrast, musical creation, particularly within contemporary rap and afrobeats culture, is planned, deliberate, and commercial. A diss track cannot be an impulsive statement, but it is a product of composition, recording, editing, mastering, and distribution. It is developed, marketed, and performed before audiences, both digital and physical. Each stage of the process reflects conscious choice and editorial control. The artist has sufficient time to reflect, reconsider, or even retract before public release. The final version represents not an unguarded reaction but a deliberate act of communication.

This difference matters deeply. In Banson v Nana(supra), the words were spoken in a market quarrel, yet the court still found them defamatory because they accused the plaintiff of dishonesty. If liability could arise from speech spoken in anger, it would be difficult to excuse calculated artistic speech that is produced through an extended and intentional process. A diss track is a publication within the meaning of the law, It is not spontaneous, but rather a deliberate form of communication intended for a wide audience. The conditions that excuse mere outbursts do not apply to such deliberate expression.

The comparison with the decision in Aubrey Drake Graham v UMG Recordings, Inc. highlights this difference in perspective. In that case, the United States District Court held that lyrical allegations in a rap rivalry were not actionable because they were rhetorical exaggeration and artistic bravado. The court relied on the cultural context of rap music and assumed that a reasonable listener would not interpret the lyrics as literal accusations of criminal behaviour. This reasoning fits within the American free speech tradition, where the First Amendment favours protecting artistic expression even when it shocks or offends. The court assumed that the audience could distinguish between performance and reality.

Such an assumption may not apply in Ghana’s legal and cultural setting. Ghana’s defamation law, shaped by both common law and customary values, attaches serious weight to communal interpretation and to the social meaning of speech. In a society where reputation functions as moral and economic capital, a diss track that alleges criminal or immoral behaviour can easily be understood as a factual statement. The average Ghanaian listeners may not always treat such lyrics as theatre.

It is not difficult for people to perceive them as statements about real character, particularly when the artist names another person directly or implies concrete misconduct. Because the music industry in Ghana depends heavily on sponsorships, public image, and brand trust, reputational damage has real financial consequences.

Unlike a quarrel spoken in passing, a diss track is carefully prepared and commercially distributed. Its release across streaming platforms, radio, and social media which ensures extensive publication. Once released, the song can be replayed, quoted, remixed, and circulated indefinitely. The harm is multiplied by the reach of digital distribution and by the permanence of online archives. This permanence places the diss track within the legal category of libel rather than slander, since the communication exists in a recorded and enduring form. The “heat of the moment” reasoning cannot logically apply to such calculated speech.

The decision in Banson v Nana also undercuts the idea that emotional context absolves responsibility. The court there recognised that even words spoken in anger may be defamatory if they impute dishonesty or moral weakness. The principle that emerges is clear: if liability may attach to impulsive speech, it is even more appropriate when the statement is prepared and published after reflection. The diss track is not a slip of the tongue, it is the product of multiple decisions to create, refine, and distribute content that may damage another’s reputation. The argument that such speech should be excused as mere artistic competition weakens once its deliberate and commercial character is acknowledged.

From a policy standpoint, recognising this difference does not amount to censorship. It simply imposes a duty of care proportionate to the power of publication. Our music industry now operates as a professional and international business. Artists are brands, songs are products, and reputation is a form of property. When lyrical rivalries descend into allegations that can be understood as factual, the law should not treat them as harmless performance. The same principles that protect traders, politicians, and professionals from defamatory harm must apply to artists whose livelihoods depend on public trust.

This reasoning does not deny that rap battles and lyrical confrontations have cultural and artistic value. Rather, it argues that the line between artistic expression and defamation must be drawn with greater precision. The key question for Ghanaian courts should be how a reasonable listener, situated in Ghana’s cultural and social environment, would interpret the lyrics. Would they see them as playful exaggeration or as credible allegations of wrongdoing? The answer will depend on context, tone, and audience expectation. Where the words suggest criminality, moral corruption, or professional dishonesty, and where they are recorded, distributed, and monetised, the defence of artistic freedom should not automatically prevail.

THE GHANAIAN RAP BATTLES AND THEIR IMPLICATION BASED ON GHANAIAN LAW.

There have been many rap battles from different generations in the our music industry, spanning from the 1990s to date. However, for this article, we would focus on two different timelines in Ghana’s music history.

The first covered across the 2000s, with a resurgence around 2009 between hiplife musician and rapper, Michael Elliot Kwabena Okyere Darko, popularly known as “Obrafour” and musician, songwriter, and creative director, Kwame Nsiah-Apau popularly known as “Okyeame Kwame”. This rap battle’s central spark was with the release of “Kasiebo” a track by Obrafour featuring Guru. In this song, Obrafour tackles an earlier mentioned statement made by Okyeame Kwame in which he claimed to be the “best rapper alive”. In this track, which was creatively made to demonstrate a radio interview session between Guru and Obrafour, with Guru asking questions and Obrafour answering. In the second verse, Guru states:

“Nkra y3n nsa aka firi Kumasi ne s3, nnwomtoni OK, nsoak)to mona, )de abaayewa bi a, adi nfie nw)twe aforo mpa, w)ayene no, wcay3 no dosodoso, awenyaa”

Which transilates to

“The message we have received from Kumasi is that the musician OK, has slept with a girl, who is seven years old, up, they have kidnapped her, they have impregnated Her”

The allegation made in Guru’s verse can only reasonably be understood as referring to Okyeame Kwame. At the material time, Okyeame Kwame was widely and popularly identified in the our music industry and in public discourse by the shorthand “OK”, a moniker derived directly from his stage name and frequently used by fans, presenters, and fellow artistes in interviews, media commentary, and musical references. There was no other prominent Ghanaian musician contemporaneously known by that designation in a manner capable of fitting the context of the song. The reference is therefore not ambiguous or generic, but one which ordinary listeners familiar with the our music scene would naturally and inevitably associate with Okyeame Kwame. Against that background, the lyrics, which allege that “OK” had sexual intercourse with a seven-year-old girl and impregnated her, amount to a direct imputation of sexual offences against a minor. Such an allegation falls squarely within the most serious category of defamatory imputations recognized under our laws, namely the imputation of a grave criminal offence punishable by imprisonment.

Such a statement is an assertion of a crime punishable by imprisonment and therefore constitutes defamation actionable per se under common law without the need to prove special damage. Authorities such as Gray v Jones [1939] 1 All ER 798 and Webb v Beavan (1883) 11 QBD 609 establish that imputing criminal conduct, particularly offences involving moral turpitude, exposes the claimant to hatred, contempt, and social avoidance, and our courts have consistently adopted this reasoning. Under customary law, the claim would be even more straightforward. Banson v Nana confirms that imputations of dishonesty, immorality, or antisocial behaviour in a communal setting are actionable per se, even where they arise in moments of anger. A fortiori, a recorded and distributed allegation of sexual misconduct with a minor is a deliberate communication that carries severe moral stigma. It would be difficult for a Our court to classify such a statement as mere vituperation, because diss tracks are not impulsive speech. They are crafted, recorded, mastered, and intentionally released, which places them in the category of libel. Libel is actionable per se, and the requirement to prove special damage does not arise.

The absence of a lyrical response from Okyeame Kwame does not convert the impugned lyrics into a rap battle in the legal sense. Defamation is assessed objectively from the standpoint of the ordinary reasonable listener, not by reference to whether the person targeted chooses to respond. Ghanaian courts do not require reciprocal artistic engagement before an allegation becomes legally significant. The controlling inquiry is whether a reasonable listener, familiar with the our music landscape at the material time, would understand the words complained of as referring to an identifiable individual and asserting a factual allegation about that person.

In the present case, the reference to “OK” must be understood in its full lyrical and contextual setting. The verse states that the allegation emanates “from Kumasi” and concerns a well known “nnwomtofo”, that is a musician, identified as “OK”. At the time the song was released, Okyeame Kwame was not only one of the most prominent musicians associated with Kumasi but was also widely referred to in the industry and in popular discourse by the shortened appellation “OK”, derived directly from his stage name. No other Kumasi based artiste of comparable prominence during that period was publicly known by that designation, nor was there any contemporaneous allegation of similar nature circulating in respect of another musician fitting that description. In those circumstances, an ordinary listener acquainted with the music scene would naturally and reasonably understand the reference to “OK” as pointing to Okyeame Kwame.

Viewed through this lens, the lyrics do not operate as abstract insult or metaphor. They convey a specific allegation of sexual intercourse with a minor, a grave criminal offence punishable by imprisonment. Ghanaian listeners are accustomed to treating such direct accusations of criminal conduct, particularly when tied to an identifiable individual and a specific location, as statements of real behaviour rather than figurative bravado. This accords with the reasoning in Banson v Nana, where imputations of moral wrongdoing were understood as serious attacks on reputation within Ghana’s communal culture.

Applying the essential elements of defamation, the statement is capable of a defamatory meaning because it imputes a serious crime. It refers to an identifiable person, namely Okyeame Kwame, through the contextual use of “OK” within the Kumasi music milieu. It was published through a recorded song that was released, distributed, and disseminated to third parties. These elements satisfy the requirements articulated in Pullman v Walter Hill and Co (1891) 1 QBD 524, Sim v Stretch [1936] 2 All ER 1237, and Knuppfer v London Express Newspapers [1944] AC 116.

The exchanges between “Shatta Wale” and “Yaa Pono” in Say Fi provide a stark illustration of how diss culture in Ghana can move beyond artistic provocation into actionable defamation. The lyrics are not framed as metaphor or coded bravado but as direct assertions of criminal conduct, sexual immorality, and social disgrace. In Say Fi, Shatta Wale accused Yaa Pono’s father of rape and alleged that Yaa Pono himself was the product of that rape. The lyrics state:

“I swear, I shock for your mother

Ano go blame am oo, but ebi your father

He rape am

Yaa your father rape am

So you, you be mistake

If you want make I continue, just say fi.”

These words amount to a direct imputation of the crime of rape against Yaa Pono’s father and simultaneously portray Yaa Pono’s mother as a victim of sexual violence. Under our laws, an allegation of rape is an imputation of a serious criminal offence punishable by imprisonment and is defamatory per se if false. Crucially, defamation law is not confined to the immediate target of a dispute. Where defamatory words clearly refer to identifiable third parties, those third parties may have independent causes of action. The lyrics do not merely insult Yaa Pono. They accuse his father of a grave crime and publicly expose his mother to humiliation and social stigma. This engages the principle that defamatory matter is actionable where it lowers the reputation of any person identifiable from the publication, whether or not that person is a participant in the underlying dispute.

In the same song, Shatta Wale further deployed language imputing same sex conduct to Yaa Pono in a derogatory manner. The lyrics state:

“See some batty man, weh ah roll with ah batty man, with ah man name Fatima,”

followed by

“Mɛn nu wo hu nɛ atsɛo lɛ Yaa.”

In Ghanaian colloquial usage, the term “batty man” is widely understood as a pejorative reference to male same sex conduct. It is not employed neutrally, but as a term of ridicule intended to diminish social standing. The legal relevance of this imputation must be understood within Ghana’s statutory context. Section 104 of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29) criminalises what the statute describes as “unnatural carnal knowledge,” including sexual intercourse in an “unnatural manner,” categorising such conduct as a criminal offence depending on consent and circumstances. Without making any moral judgment, the existence of this statutory provision means that imputations of same sex conduct may reasonably be interpreted by the ordinary Ghanaian listener as allegations of criminal or morally proscribed behaviour.

Under Ghanaian defamation law, the central question is whether the words complained of would lower the person concerned in the estimation of right-thinking members of society. Where sexual conduct is invoked as a basis for ridicule, disgrace, or social exclusion, particularly against the background of Act 29, the imputation is capable of defamatory meaning. This approach aligns with received common law authority such as Kerr v Kennedy, which treated imputations of same sex conduct as defamatory per se, and with Ghanaian customary law jurisprudence such as Hotchand v Gentleman Salam, which recognises that words imputing sexual impropriety are actionable unless clearly understood as mere quarrel abuse.

The language used in Say Fi cannot reasonably be characterised as impulsive vituperation uttered in the heat of a personal quarrel. It forms part of a deliberately recorded and commercially distributed diss track. The lyrics extend reputational harm beyond the immediate target to identifiable third parties who are not participants in the feud. When assessed against Ghana’s communal understanding of dignity, family honour, and reputation, such imputations are capable of constituting actionable defamation if false and cannot be dismissed as harmless artistic bravado.

In Gbee Naabu, Yaa Pono escalated the dispute by making a series of direct and specific allegations against Shatta Wale that fall squarely within established categories of defamation under our laws. The lyrics include the following statements:

“girls girls, shatta wale get aids oo, shatta michy no no say she dey spread oo, the pikins all u born no bi ur own oo, de whole ghana nim, ɔbɔ pampers.”

These statements allege that Shatta Wale is HIV positive, that his partner is spreading the disease, that his children are not biologically his, and that he “ɔbɔ pampers.” In Ghanaian local parlance, the expression “ɔbɔ pampers” is commonly used as a derogatory insinuation of same sex conduct. The phrase is not descriptive. It is deployed as a term of ridicule and social degradation, intended to portray the subject as sexually deviant in the eyes of the public.

The allegation that a person is suffering from HIV or AIDS falls within a well-established category of defamation. In Bloodworth v Gray, imputations of a contagious and repulsive disease were treated as defamatory per se because they naturally lead to social avoidance and stigma. Ghanaian courts have consistently recognised the social force of such imputations. The claims regarding the paternity of Shatta Wale’s children further impute sexual immorality and dishonesty, both of which strike at personal honour and family integrity. The combined effect of these statements is to portray Shatta Wale as diseased, sexually immoral, and socially untrustworthy.

The use of expressions such as “ɔbɔ bambers,” when understood against the background of Section 104 of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29), reinforces the defamatory character of the imputation. Where language commonly associated with criminalised or socially condemned sexual conduct is used as an insult, the ordinarylistener may reasonably understand it as an allegation of unlawful or morally reprehensible behaviour. This brings the imputation within recognised heads of defamation, including imputations of crime, sexual impropriety, and unfitness in one’s profession or calling.

These statements were made in a recorded song, intentionally released and widely disseminated across radio, streaming platforms, and social media. They therefore constitute libel and are actionable without proof of special damage. Applying the test of the reasonable listener, it would be difficult to characterise these lyrics as symbolic exaggeration or harmless performance. In a society where reputation functions as moral, social, and economic capital, allegations of HIV infection, sexual deviance, and illegitimacy are readily understood as factual claims. If litigated, a court would likely conclude that the lyrics in Gbee Naabu cross the boundary from artistic rivalry into actionable defamation under both common law and customary law.

A practical example in this regard could be the feud between the Ghanaian rappers “Medikal” and “Strongman” in mid-2019. The feud started after “Medikal”, the then VGMA Rapper of the Year, stated that he had “saved” the Ghanaian rap music. “Strongman” responded to this claim with a diss track. In their feud, Strongman in his song; “Don’t Try” made serious allegations against Medikal that if he subtracted his fraud money from his real money, he could not even buy a bicycle. The feud between the two rappers started when Medikal made a post on twitter in 2019 (now “X”) that he had been carrying the Ghanaian rap industry for the past four years. This post did not rub off very well with a host of rappers who also took to social media to express their opinions on the matter with the arguably one of the most vocal ones being Strongman. After the social media backlash, Medikal released the first song that would ignite the feud, the title of the song was “To whom it may concern” and although no direct references were made it was quite clear that it was addressed to Strongman. With lines like

“these yesterday rappers dey bore me, I for charge for features whenever they call me. Just because I live in one house with the kids does not mean them be homies, draw the line… You claim hot emcee but you still order uber,”.

Strongman in response released two songs back-to-back, namely “don’t try “and “immortal”. In the song ‘Don’t try’, Strongman made the following statements

“Subtract your fraud money, from the real money, nsesa na3b3ka 3kyere no it be your music money, it no fit buy you bicycle, my man you’re sounding funny, ka nokor3 kyer3 amansan na that be your testimony’

Throughout the song, statements were made that made it obvious that direct references were being made to Medikal. Strongman mentioned the titles of two previous hit songs and even went as far as mentioning his girlfriend at the time and his ex-girlfriend before that. He made the following statements:

“Controversies all the time εnoa na εmaa wo hit.Too risky ne Omo ada nyinaa εmaa na εboa wo hit.”

After the release of this song, it sparked a protracted discourse on social media and mainstream media for weeks on the alleged or purported fraudulent activities of Medikal.

In the opinion of the authors, our courts should not in likemanner treat these lyrics as rhetorical exaggeration because the statements are specific, factual in tone, and communicated through deliberate and commercially produced songs. They exist in recorded form and therefore constitute libel rather than slander, meaning they are actionable without proof of any specific financial loss. The reasonable listener, unlike the American listener described in the Drake decision, does not automatically interpret such lyrics as theatrical persona building. In a society where reputation is a form of economic and social capital, an accusation that an artist is HIV positive, a rapist, gay, or a fraud can easily be understood as a statement of actual fact. If either party were to bring a defamation claim, the court would therefore focus on whether the lyrics impute a verifiable fact, whether the words refer to the claimant, and whether publication occurred. All three elements would clearly be satisfied. The legal analysis strongly suggests that the “Say Fi” and “Gbee Naabu” battle, if litigated, could result in liability because the content goes far beyond artistic provocation and directly asserts criminal and immoral conduct capable of harming reputation in Ghana’s social and commercial environment.

Also in April 2020, Sarkodie ( Michael Owusu Addo) fired some subliminal jab at fellow rappers in Ghana on sound engineer Appietus new hip-hop beat that was part of a social media challenge called #LockDownShow. Asem (Nana Wiafe Asante-Mensah) took Sarkodie on with a an equally fresh hot freestyle which went viral on Twitter. In the said freestyle, Asem called out Sarkodie for always making comparisons and bragging about his achievements and later called him by his social media alter ego “Kabutey”. Sarkodie released ‘Sub Zero’, a track laden with bars perceived as directed at Asemand other perceived Ghanaian rappers. Lines like

“rappers a mo a dissi me a mootwen reply, de3 moreye no de3 eno go fly, m’adi kan aka akyer3 mo dada mom moa moho namo mmra na me’ndissi obi a ne bottom ay3 dry. Woy3 relevant aa wobetua 10k, mo a y3tee mo nka aky3 no nso de3 5k, but moa pressure no faa moa mo’adwane ak)hy3 aman)ne, meam3yi makoma mu ama mo 1k 3w)s3 mob3 pa akyew, br3 woho ase, meyeyaw koraa 3w)s3 wob3da ase.”

reinforced the perception that he was dismissing Asem’s attempts at rekindling relevance and that he is not ready to beef any artiste who is broke.

Asem’s immediate response, posted on social media with a series of freestyle videos, questioning Sarkodie’s relevance and suggesting Sarkodie needed to diss him to boost his own career, even calling him out for being and “over-hyped’ artiste. and followed by diss tracks, reignited one of Ghana’s most public lyrical rivalries.

In Simpson v MGN Ltd supra, the English Court of Appeal held that words must be interpreted in their full context, including the genre and audience. To us this reasoning resonates strongly with Ghanaian audiences. Rap battles in Ghana, from Reggie Rockstone’s era to the current generation operate within a shared understanding that lyrical insults are part of artistic competition. Therefore, Sarkodie’s mockery of Asem’s “fading star” or Asem’s depiction of Sarkodie as a “corporate sellout” likely fall under artistic hyperbole rather than defamation. As we emphasize that the reasonable listener in Ghana’s music culture understands diss as performance, not factual journalism.

Furthermore, in 2018, Shatta Wale launched several verbal attacks on Sarkodie during interviews and public appearances, accusing him of hypocrisy, allegedly being broke, criticizing his music style and his authenticity as a rapper and stinginess.

Sarkodie’s response came in the form of My Advice, a masterclass in calm but cutting lyricism. Without mentioning Shatta Wale by name, the track’s references were unmistakable. Sarkodie raps:

“if being poor be like me then father I beg you just bless me with poverty, I don’t want to snitch on my nigga, but f**k all the bragging and chill cos honestly your whole bank account can’t buy you a tear rubber VO, but you claiming supremacy. F**k outta here you be full batti.

In the second verse, the rapper continued to take lyrical jabs at Shatta Wale:

“brand no be strong enough, if you be strong keep quite you go soon commot. I stayed mute one year saf full support, you showed d**k one day you go show buttocks”

and later adds:

“this no be beef just stay and listen. Me and you cool no crazy friction. But my frustration be say I dey try move Ghana forward but I’m still babysitting. New money, new car, new house so you can’t think far…….. 3y3 wa jimi krakra stay focused”

The song immediately sparked debate across media about the limits of lyrical expression, particularly when lyrics carry factual insinuations about a person’s character or conduct.

In My Advice, Sarkodie portrays his target as immature, boastful, and financially reckless. Lines such as

“You dey brag say you rich, but your bank no dey show am”

can easily be construed as personal attack. This impugnsirresponsibility and deceit.

Conversely, Shatta Wale’s responses, particularly in his song titled Little tip, he started by saying

“ anka anka mom ana y3 de y3 star anka kwabena awuke woakwabena awuku anka oy3 Galaxy siaaa…..the cash, the mansions, the cars (you no get some), my 3 range rovers (you no get some), my gold chain for my neck (you no get some), my rolex, diamond ring (you no get some)……. If you see boys dey shine p3 you say you dey help dem STRONGMAN, so when you go stop lie to Ghanaians AKWABOAH, akoayi y3 aboa…acehood no she you be liar, thief stolen car you no be buyer, da b3n na Kaabutey b3 tor Panamera, ago make your fans stop dey huh! And do de paah paah paaah…”

To let his audience aware he was dissing Sarkodie, he boldly mentioned his name in the chorus; “ Sarkodie yie, you know me yie but you don’t know me yie, mi I get some dirty vibes, east legon and you say klagon, you know how much be one plot of land? JON”

Shatta wale however also made some defamatory claims against Sarkodie in the same song. He sang

“ wo mom ate s3 kwahu pipor, if you say me abi batty you for prove oooo, ano be like dem stars you dey use oo, immigration go bring your cocoain news ooo, you just enter my life at dey wrong time, you no dey see she as you call my name you go worldwide”

These statements could, on face value, amount to allegations of dishonesty, theft and allegations of drug usage.

In this sense, Banson v Nana and Drake v UMG represent two sides of the same legal puzzle. The former prioritises the protection of communal dignity and reputation, while the latter emphasises individual creative freedom. Ghanaian jurisprudence must find a balance that respects artistic innovation without undermining the value of personal honour. In a digital culture where music doubles as speech and speech doubles as commerce, that balance requires careful judgment. Spontaneity can excuse the unguarded tongue, but deliberation anchors responsibility. What separates mere vituperation from defamation is not the form of the expression but the intention, preparation, and impact behind it.

VI. INDUSTRY AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS IN GHANA

A. Music Industry Practice

Public rivalries can increase audience engagement. However, reckless criminal insinuations risk civil liability.

B. Contractual Considerations

1. Morality clauses.

2. Defamation risk review before publication.

3. Label oversight mechanisms for content implicating reputational harm.

C. Education and Governance

Industry associations and entertainment-law practitioners should promote awareness of defamation standards and responsible lyrical content.

The Standard for Striking Out Pleadings in Ghana

The power of the courts in Ghana to strike out pleadings is one of the most delicate and exceptional judicial discretions. It is exercised under Order 11 Rule 18 of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2004 (C.I. 47) and also under the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court. The principle behind this power is to prevent abuse of court processes, eliminate frivolous or vexatious litigation, and ensure that justice is administered efficiently without unnecessary trials. However, because the right to be heard is a fundamental aspect of justice, this power is to be exercised sparingly and with great caution.

Standard for striking out Pleadings

Order 11 Rule 18(1) of C.I 47 provides as follows:

“The court may at any stage of the proceedings order any pleadings or anything in any pleading to be struck out on the grounds that;

(a) it discloses no reasonable cause of action or defence;

(b) it is scandalous, frivolous or vexatious;

(c) it may prejudice, embarrass or delay the fair trial of the action; or

(d) it is otherwise an abuse of the process of the court,

and may order the action to be stayed or dismissed or judgment to be entered accordingly.”

Rule 18(2) further stipulates that:

“No evidence whatsoever shall be admissible on an application under rule (1)(a).”

This provision means that, when an application to strike out is made on the basis that a pleading discloses no reasonable cause of action, the court must determine the issue solely from the pleadings themselves. It cannot receive affidavit evidence or other extrinsic material, since the court must deem the factual averments in the statement of claim to be true for the purpose of the application.

This principle was affirmed in Ghana Muslim Representative Council v. Salifu , and restated in Jonah v. Kulendi & Kulendi , where the Supreme Court emphasized that the rule in both the old and current High Court rules must be interpreted consistently that the applicant is deemed to admit the truth of the opponent’s averments when moving under Order 11 rule 18(1)(a).

The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court

Aside from the rules of court, superior courts in Ghana possess an inherent jurisdiction derived from the common law. This jurisdiction exists to control the court’s own process, prevent injustice, and stop abuse of procedure. In Bremer Vulkan Schiffbau und Maschinenfabrik v. South India Shipping Corporation Ltd , Lord Diplock described inherent jurisdiction as the court’s general power to control its own procedure so as to prevent the court from being used to achieve injustice..

Thus, while Order 11 Rule 18 provides a procedural foundation for striking out pleadings, the inherent jurisdiction of the court represents a broader and more flexible power one that is exercised to protect the integrity of judicial proceedings even in the absence of an explicit procedural rule.

Difference Between Order 11 Rule 18 and the Inherent Jurisdiction

Though both mechanisms yield similar results i. e the dismissal of an action or pleading, they differ in scope and procedure. An application under Order 11 Rule 18(1)(a) excludes affidavit evidence, while an application under the court’s inherent jurisdiction may rely on extrinsic evidence.

This was clarified in Okofo Estates Ltd v. Modern Signs Ltd, where Akuffo JSC stated:

“In view of the clear differences in the established practices and procedures for invoking the two powers, the two cannot be considered to be interchangeable or simultaneous, unless they are both specifically applied for.”

Furthermore, Vinson v. The Prior Fibres Consolidated Ltd held that an application may invoke the court’s inherent jurisdiction even without labeling it as such, provided its grounds clearly show that such jurisdiction is being relied upon.

Application and Timing of the Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction to strike out is discretionary and may be exercised “at any stage of the proceedings.” However, courts have repeatedly stressed that such applications must be made promptly and not used to delay proceedings that have already advanced to trial. According to Bullen & Leake & Jacobs, Precedents of Pleadings;

“Although the application may be made at any stage of the proceedings, still it should always be made promptly and as a rule soon after the service of the offending pleading… the court may refuse to hear such an application after the action is set down for trial.”

This cautionary approach was adopted by the Supreme Court in Nene Fiesu Gblie Gbenartey & Another v. Netas Properties & Investment & Others . In that case, the defendants applied to strike out a claim after issues had already been settled for trial which the lower courts allowed. Upon appeal to the Supreme Court, it held that although the rule allows striking out “at any stage,” the application was procedurally improper given the advanced stage of proceedings. Anin Yeboah JSC (as he then was) emphasized that striking out should only be used in plain and obvious cases and not where contentious issues exist that require trial.

Cautionary Principles and Judicial Discretion

The courts have consistently maintained that the power to strike out pleadings should be exercised with utmost restraint. In Dyson v. Attorney-General, Fletcher-Moulton LJ warned:

“Our judicial system would never permit a plaintiff to be driven from the judgment seat in this way… except in cases where the cause of action was obviously and almost incontestably bad.”

This principle was echoed in Republic of Peru v. Peruvian Guano and Hubbuck & Sons Ltd v. Wilkinson Heywood & Clark , where courts cautioned against prematurely terminating proceedings without a full trial, except where a claim is clearly unsustainable or frivolous.

In Ghana, Professor Stuart Sime, in A Practical Approach to Civil Procedure, similarly observed that ;

“The jurisdiction to strike out is to be exercised sparingly, because striking out deprives a party of its right to a trial… Striking out is limited to plain and obvious cases where there is no point in having a trial.”

Allegations of Fraud and the Need for a Full Trial

One key restriction on the use of this jurisdiction arises where fraud is alleged. Allegations of fraud require evidential proof and therefore cannot be summarily dismissed. In OkofoEstates Ltd v. Modern Signs Ltd (supra), Edward Wiredu JSC emphasized:

“An allegation of fraud goes to the root of every transaction… A denial of an allegation of fraud raises a triable issue which a court cannot determine summarily.”

Similarly, in Gblie Gbenartey v. Netas Properties (supra), the Supreme Court condemned the lower court’s dismissal of a case involving allegations of fraud without hearing evidence, describing the approach as “a violation of natural justice.”

Guiding Principle for Striking Out Pleadings

The general discretion of courts in striking out pleadings is well summarized in Halsbury’s Laws of England (4th ed., Vol. 37, para. 430):

“The powers are permissive, not mandatory, and will be exercised in the light of all the circumstances. The court will not lightly drive a party from the seat of judgment, but the jurisdiction will be exercised in the clearest of cases to prevent harassment and expense from frivolous, vexatious or hopeless litigation.”

Therefore, under Ghanaian jurisprudence, the standard for striking out pleadings is guided by both statutory and inherent judicial principles. The courts will only strike out a claim where it clearly discloses no reasonable cause of action, is frivolous, vexatious, or amounts to an abuse of process. The power must be exercised sparingly, cautiously, and only in plain and obvious cases, especially not where factual disputes or allegations of fraud exist that require full evidential examination. The ultimate aim of this jurisdiction, as the Supreme Court consistently reminds, is not to drive parties away from the judgment seat but to uphold the integrity of justice and ensure fair trial in accordance with due process.

VII. CONCLUSION

Drake v UMG reinforces that diss-track accusations operate within a protected artistic speech tradition under U.S. law. Ghana balances artistic expression with stronger protection of reputation. As Ghana’s music industry evolves, legal guidance and contractual discipline can promote creativity while safeguarding rights and public trust.

AUTHORED BY;

• Nana Kwadwo Agyei Addo

• Justice Osei-Boamah

• Stephanie Acquah

• Abena Boakye

• Serwaa Amihere

Latest Stories

-

Over 1,000 Kenyans enlisted to fight in Russia-Ukraine war, report says

3 minutes -

Robert Mugabe’s son arrested in South Africa on suspicion of attempted murder

14 minutes -

Minority rejects Security and Intelligence Agencies Bill, cites ‘excessive executive powers’

17 minutes -

Islamist militants accused of killing 34 in raids on Nigerian villages

24 minutes -

DVLA commissions new premium service centre in Kumasi to better serve customers

27 minutes -

BoG warns of downside risks to cedi as a result of dividend payments

38 minutes -

Consumer spending posted mixed performance in 11 months of 2025 – BoG

40 minutes -

Wa District Magistrate Court convicts three for unlawful possession of firearms and ammunition

1 hour -

There is no governance gap at Defence Ministry – Kwakye Ofosu

1 hour -

Mahama to appoint Defence Minister ‘at the right time’ – Government

1 hour -

GRA boss donates to Mahama Cares

1 hour -

Education Ministry warns of severe consequences for assault on teachers

1 hour -

Absence of substantive Defence Minister a strategic risk – Amankwa-Manu

1 hour -

CDD reports tangible fall in cost of living during first year of Mahama administration

2 hours -

Protest is not petty politicking – Cocoa farmers urge gov’t to heed their demands

2 hours