Audio By Carbonatix

On February 23, 2022, 75-year-old Fuseini Zakaria passed away at his residence in Nanton-Zuo, a community within the Tamale South Municipality in Ghana's Northern Region. In line with Islamic tradition, he was buried the same day in a nearby cemetery.

Mr. Zakaria left behind a wife and four children. Four months later, his eldest son, Yakubu Zakaria, and younger brother, Salifu Fuseini, visited his grave to pray and seek Allah's blessings for the departed.

Before his death, Mr. Zakaria had been diagnosed with kidney failure at the Tamale Teaching Hospital. Doctors advised him to stop drinking water from the community's main source, triggering widespread concern among locals who suspected that the heavily polluted dam water might have been responsible for his illness.

At their modest family home, where Mr. Zakaria died, his son, Yakubu, shared the painful journey of his father’s illness. He had cared for him both at home and during hospital visits.

While there were no official documents linking Mr. Zakaria’s kidney failure directly to the heavily polluted dam water, Yakubu insisted that doctors believed the contamination was the cause.

“They carried on tests upon tests and concluded it was water-borne disease that led to the kidney failure,” Yakubu recalled.

He explained further, “That information came through their tests and examinations or based on their experience. Initially, they advised us not to provide dam water to him, stating it was unsafe. They didn't explicitly tell us that it would worsen, but the initial warning prompted our apprehension. Subsequently, we decided to abstain from using dam water for drinking. We only use it for washing and bathing, having witnessed the adverse effects it had on us."

Buying clean water became a financial burden, but the family did their best.

“During his illness, the doctors explicitly advised against giving him dam water. They emphasized the use of Voltic, which posed a financial challenge for us given our community's economic circumstances. Despite the struggle, we made our best efforts throughout his illness to avoid giving him dam water. We resorted to using sachet water or Voltic instead,” Yakubu said.

JoyNews Investigates: Is Nantong-Zuo's Water Safe?

What appears to be a chocolate drink is, in fact, the drinking water available to Nantong-Zuo residents. Without clean alternatives, locals are forced to rely on the murky and heavily contaminated dam water.

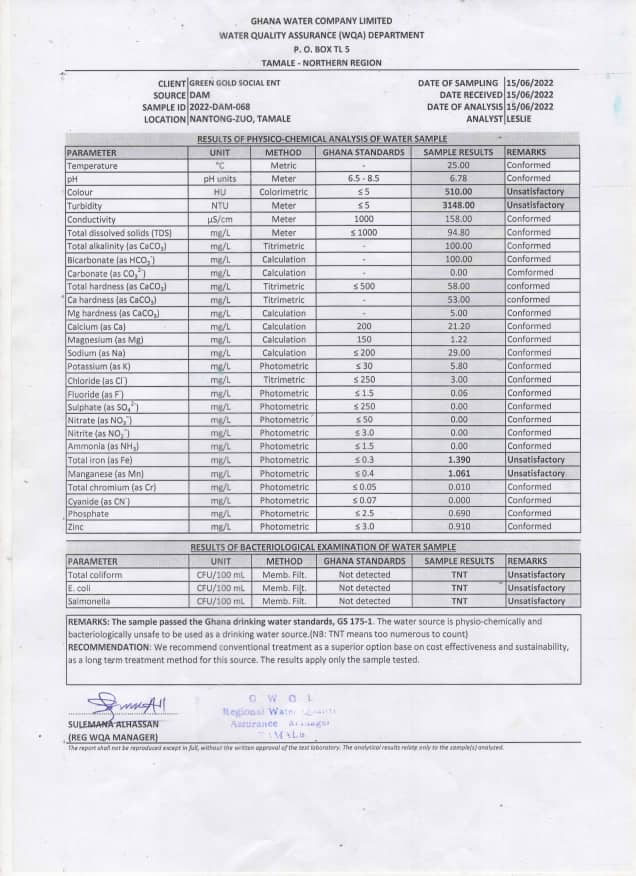

JoyNews collected a sample and submitted it to the Ghana Water Company’s Regional Quality Assurance Department in the Northern Region for testing and analysis. The results were alarming.

Regional Water Quality Assurance Manager, Sulemana Alhassan, explained, “Instinctively, when you see it, you know that it's not potable. But you can't carry this sample around to show people. The best thing is to analyze it and turn this water into data, and that is exactly what we have done.”

He added, “The physical and chemical parameters do not meet regulatory requirements. Ghana has set standards, and any analyzed sample must conform. This water fails the test.”

Most disturbing, he said, was the microbial content.

“When we did the analysis, we realized that, ideally, you count the number of microorganisms in water to determine contamination. For drinking water, there shouldn’t be any microorganisms. In this case, we couldn't even count them. That is why we put 'TNT' (Too numerous to count),” he stated.

Mr. Alhassan emphasized that while contaminated water may not cause instant harm, prolonged use could lead to serious health problems.

“Some consequences appear immediately, especially in immune-compromised people like infants, pregnant women, the elderly, and the sick. For others, the effects take time. But continuous consumption of untreated water like this will eventually cause harm,” he warned.

"So, when they are using this (referring to the water), the consequences are dire and quicker than somebody who appears to be healthy. That one, it will take time. So, once the person continues to consume this (referring to the water) without treatment, you will experience varied degrees of injuries,” he explained.

Expert Assessment at Tamale Urology and Modern Surgical Centre

Because Mr. Alhassan was unable to directly connect the lab findings to Yakubu’s claims, the team sought further expert insights at the Tamale Urology and Modern Surgical Centre — a specialized facility in Nantong-Zuo built by Le Mete Ghana, a Tamale-based Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) focused on urology and surgical care. The centre, which also trains urologists, offered critical insights into the water test results.

Consultant urologist Dr. Akis Afoko, who oversees the centre reviewed the report and explained that the water contains a high level of salmonella, a bacterium commonly responsible for typhoid fever.

“The water contains a substantial amount of Salmonella, a common cause of typhoid fever. A third of children in the community are admitted due to this. It also contains E. coli, which comes from human excreta,” he explained.

Dr. Afoko explained that human waste enters the water through faeco-oral transmission, making it highly unsafe when bacterial levels are as excessive as reported — “too numerous to count.” He noted that many residents, including schoolchildren, frequently seek treatment at the facility for severe diarrhea, often forcing children to miss school due to persistent illness.

“Heavy bacterial contamination, as shown in the report, makes this water extremely unsafe. Many residents suffer from severe or bloody diarrhea, often needing surgery due to complications like bowel perforation caused by typhoid,” Dr. Afoko added.

He confirmed Yakubu’s claim.

“I assume you're referring to Afa Zakaria, who was our father and brother. Indeed, he had a severe infection that resulted in renal failure. Sometimes, the antibodies produced to fight infections attack the kidneys,” he explained.

Mr. Zakaria suffered prolonged kidney problems that eventually progressed to terminal renal failure. Dr. Afoko noted that combining kidney failure with diarrhea poses serious health risks, as it leads to dehydration and further electrolyte loss. Since kidney failure already disrupts the body’s electrolyte balance, diarrhea can quickly worsen the condition, often beyond recovery.

Dr. Afoko also raised concerns over agricultural runoff and pollution from pesticides and plastics that enter the dam, worsening contamination.

He shared disturbing trends.

“We are seeing bladder and kidney cancers in very young people. Typically, these cancers occur in those aged 60 to 70. Here, some as young as 20 are terminal. We also find many cases of kidney stones, even in a seven-month-old child,” he said.

He added, “Some children are born with undescended testicles or deformed penises. We are seeing significant reproductive health issues linked to water pollution.”

Reproductive Impact: A Future at Risk

Dr. Afoko stressed that data clearly shows the serious health risks linked to drinking the contaminated dam water. As a research-focused expert, he expressed deep concern about the scale of the problem, not only causing frequent illnesses, hospital visits, and deaths, but also affecting the reproductive health of many young people in the community.

The urologist warned that the contaminated water is threatening the future of the community.

“Younger people are having smaller testes than older people. And what is the future of any country if, due to pollution from plastics and pesticides, you can’t reproduce?” Dr. Afoko lamented.

Ultrasound and semen analysis show that men under 35 have smaller testicular volumes, poor sperm motility, and abnormal sperm shape.

“They are having smaller volumes, and the motility is decreased in the younger people, and the morphology is also abnormal,” he noted.

He displayed kidney stones extracted from a two-year-old and a 32-year-old man who lost his kidney. “It was from contaminated water. These patients are in pain. They are losing their kidneys,” he said.

Residents React with Despair

Salifu Fuseini, Zakaria’s brother, was heartbroken upon hearing the doctor’s revelations.

“I was saddened by what the doctor said about contaminated water and the diseases it can spread,” he said.

Back at the dam, children were seen drinking the same polluted water. Despite awareness, residents feel they have no choice.

Yakubu Habiba has spent hundreds of cedis on treatment.

“I spent about 600 cedis at the hospital. They gave me infusions and medications. The doctor said the water caused my illness,” she said.

A student at Anbariya Senior High School (SHS), Zubaidu Hazifa, said, “We use it for every purpose. My parents, siblings, and I all drink and cook with it.”

Residents spend at least four hours fetching the unsafe water. Some, like Zubeiru Musah, have relied on it for decades.

“I have been consuming this dam water for over 40 years. You keep drinking it until you fall sick. Then a doctor tells you the cause,” he said.

Water resources development engineer, Fadlu Rahman Mashod, estimates that a mechanized borehole with filtration would cost between ₵450,000 and ₵650,000, while a small community water-treatment system would require ₵1.2 million to ₵1.8 million. Annual maintenance alone would cost between ₵35,000 and ₵48,000.

According to him, such infrastructure could eliminate 70–85% of Nantong-Zuo’s water problems. Yet, despite at least four documented submissions to district authorities and NGOs since 2018, nothing has materialized.

“What we need is not sympathy; we need action. Our people are dying slowly because we are not a priority,” lamented community leader Fuseini Salifu.

In response to years of neglect, residents established a nine-member volunteer water-watch group to discourage waste dumping and teach basic household water safety. Some families use cheesecloth and boiling methods to treat water, but these only remove coarse particles — not chemical pollutants or dangerous microbes.

Experts warn that without structural investment and strict enforcement, contamination will worsen, especially as the population grows.

National Water Access: The Bigger Picture

Despite progress, water inequality remains a problem in Ghana. According to the Ghana Statistical Service’s 2022 Demographic and Health Survey, nearly one in five Ghanaians (19.1%) lacked adequate access to drinking water in the month leading up to the survey. The situation was worse in the Northern Region, where one in three people (32.1%) did not have enough clean water to meet their needs.

According to UNICEF, 11% of Ghanaians still rely on unsafe surface water. Shockingly, 76% of households risk consuming contaminated water, and only 4% treat their water properly.

Time spent collecting water is strongly linked to poverty. Poorer households are over 20 times more likely to spend 30 minutes or more on water collection. In the Northern Region, the situation is worse than in the capital, Accra.

Women and children bear the brunt, particularly in poor communities like Nantong-Zuo, where accessing clean water is a daily burden.

Where Is the Political Will?

Residents and experts alike blame the lack of political will.

“What we need is not just words, but action,” said Madam Habiba. “Politicians promise change, but nothing changes.”

Dr. Afoko agreed, saying that without real commitment from leaders, efforts by health workers remain futile. “The community's future is at risk,” he said.

Local authorities declined to comment. Residents insist they deserve clean water and demand urgent action.

“We need leaders who will prioritize our well-being over political interests. Our lives depend on it,” said Fuseini.

Clean Water a Human Right: AHAIC 2025

At the 2025 Africa Health Agenda International Conference (AHAIC) in Kigali, Rwanda, health leaders called for urgent reforms in Africa’s health systems. They stressed prevention, not just treatment.

Chief Executive Officer of Amref Health Africa, Dr. Githinji Gitahi, said hospitals should be for repair only: “Health is created at home.” He called clean water the backbone of public health.

His call echoes strongly in Nantong-Zuo, where residents are falling sick and dying from contaminated water.

Dr. Gitahi added, “When you have little money but most of it is geared towards tertiary and secondary healthcare, it means that African countries are waiting for the floor to get wet to mop it, instead of stopping the leaking tap.”

Speakers at AHAIC referenced the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration, which recognizes health as a fundamental human right. Yet, primary healthcare (PHC) remains underfunded.

Dr. Gitahi said 80% of Africans seek healthcare at the PHC level, but investments favor expensive, curative services. “If we want sustainable health systems, we must redirect investments to PHC,” he said.

WHO Africa’s outgoing regional director, Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, said inequality, climate change, and environmental degradation are reversing health gains. “One constant has been our collective commitment to building a healthier, stronger Africa,” she said.

Seeking Sustainable Solutions

Breaking the cycle of water contamination in Nantong-Zuo demands more than temporary fixes. It requires long-term, sustainable solutions backed by science, infrastructure, and political will.

Experts interviewed for this investigation point to three workable solutions: A conventional treatment system would remove turbidity, bacteria, and harmful chemicals, producing clean, safe drinking water.

Water Quality Assurance Manager, Mr. Alhassan, explained that such systems effectively eliminate suspended matter, color, and dangerous microbes.

After treatment, the water must undergo pH adjustment and laboratory testing to ensure it is free from any harmful residue.

He added that adjusting the water’s pH level may also be necessary. After treatment, the water must be thoroughly tested to ensure that it is safe and free from harmful chemicals or microbes.

"If possible, we do PH adjustments and then, after that, you now test the water to see if the treatment process is, you know, optimum, is good such that the finished water would not contain harmful microorganisms - chemicals that can be injurious to human life."

While he emphasized the need for conventional treatment, Mr. Alhassan also mentioned possible alternative water sources such as drilling boreholes or tapping underground water.

These sources may require less treatment if the underground water table is clean and uncontaminated.

"You can drill the borehole and then maybe that one may not require so much treatment if you are lucky and the water table is good."

Dr. Afoko and other experts confirmed that underground water exists in the area, though at considerable depth. With advanced geological mapping and hydro-surveys, one or two high-yield mechanised boreholes could significantly reduce the community’s dependence on the contaminated dam.

Experts warn that infrastructure alone is not enough; communities must be able to detect danger early.

One of the most practical and affordable monitoring methods for low-resource communities is the Portable Microbial Test Kit.

The kit is extremely simple to use. Residents collect a small water sample in a sterile bottle, add a reagent and wait 24 hours. If the water is contaminated, the liquid changes colour, giving an instant warning.

Because the kits require no electricity, no laboratory and no technical expertise, they are already used in parts of Ghana. They can also be stored for months without refrigeration, making them ideal for rural communities like Nantong-Zuo.

This kind of low-cost testing helps residents to detect danger early, track contamination trends, build community-generated data, and hold authorities accountable.

Meanwhile, many residents are left with no choice but to keep drinking the contaminated water, knowing well the risks involved.

"Yes, if I don't stop drinking the water, then it is because I have no option. But if I have a way, I will stop because I know the water is not good for my health," expressed Yakubu Habiba, one of the residents.

Fuseini Salifu, another resident, echoed similar fears. He called on those in a position to help to come to the aid of the community.

"I saw that, given the current course of events explained by the doctor, the Zuo community is in danger. But how do we get out of this danger? We, as a community, have nothing if the wealthy people who can assist us do not do anything."

Until clean water becomes a reality in communities like Nantong-Zuo, preventable illnesses and deaths will persist.

The message from AHAIC is clear: bold decisions and targeted investments in primary healthcare, especially clean water, are the key to a healthier Africa.

Latest Stories

-

GNFS to launch automated fire safety compliance system to modernise regulation

3 minutes -

NALAG president commends Local Gov’t Minister for payment of assembly members’ allowances

5 minutes -

Is having a physical security operations center in your business worth it?

8 minutes -

Asiedu Nketia recounts fierce political wars in Ajumako-Enyan-Essiam constituency

14 minutes -

NRSA sets up committee to probe road crashes involving Toyota Voxy

30 minutes -

Cocoa farmers decry the adverse impact of producer price cut on livelihoods

36 minutes -

Families who lose relatives to ‘no bed syndrome’ must sue health facilities – Dr. Nawaane

36 minutes -

Ghana Sports Fund: Dr. David Kofi Wuaku outlines vision for Youth Empowerment growth through sports

50 minutes -

NUGS President urges sustainable digital governance

53 minutes -

National Investment Bank kicks off Ghana Sports Fund with landmark seed donation

55 minutes -

Two young siblings found dead in unsecured manhole

1 hour -

Cocoa Prices, Producer Prices, and the Smuggling Debate: What the data actually suggests

1 hour -

CRAG signs vehicle finance deal with Bank of Africa to boost fleet expansion

1 hour -

Cocoa price cut best policy decision to transform sector – Majority

2 hours -

Gunnyboy emerges as one of Ghana’s fast-rising dancehall voices in 2026

2 hours