Audio By Carbonatix

History isn’t a dusty archive. It lives in the names we place on roads, schools, airports and monuments.

These markers aren’t just labels; they broadcast values to citizens, visitors, and especially to our children growing up, trying to understand who we are.

That’s why the debate over renaming Kotoka International Airport matters so much.

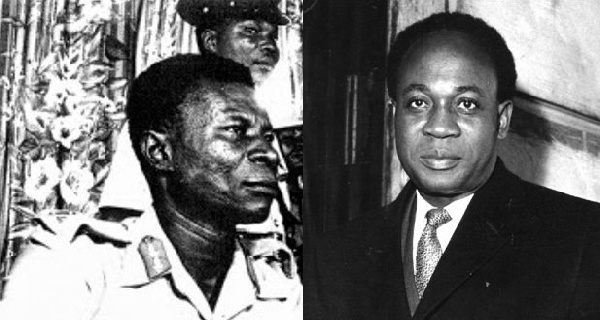

We celebrate Kwame Nkrumah as Ghana’s greatest president, a leader of independence, a visionary for African unity.

Across the continent, he’s lauded as one of the most influential Africans of the last millennium.

Yet at the same time, we honour Emmanuel Kotoka, a key figure in the military coup that overthrew Nkrumah in 1966, by naming our main international gateway after him.

Ask yourself: How does that square with our professed love of democracy?

How can we teach young Ghanaians that democratic governance is our core value when one of the first things visitors see on arrival is a celebration of someone who helped dismantle our first constitutional government?

Monuments and names are chosen for effect. They tell a story about what we admire, what we want others to know about us.

Naming our airport for someone associated with a coup is not a neutral historical footnote: it is a statement. And that statement clashes with the narrative we claim to hold dear.

Is Kotoka a hero? If he is, why? By what measure of heroism – strategic, moral, democratic – do we elevate him above others?

If he is not a hero, then why should everyone who enters Ghana be greeted with his name, prompting the inevitable question: “Who is Kotoka?” Only for the answer to be, “He overthrew Nkrumah”?

And here’s where it gets deeper: our own cultural logic already tells us that names carry weight.

In many Ghanaian traditions, children are named after ancestors, events, virtues, or aspirations.

A name is a blessing, a memory, a legacy. We don’t give a child a name that honours someone dishonourable — that could bring confusion or bad omen into the family.

Public monuments should follow the same logic. If we wouldn’t name a child after someone whose actions we regret, then why name a national asset after them?

We are teaching the next generation and, signalling to the world, something contradictory: that we hate coups, yet we are comfortable celebrating a coup maker in one of the most prominent ways conceivable.

That confusion isn’t just intellectual, it’s moral and symbolic.

This isn’t about erasing history. It’s about choosing which parts of history we elevate and why.

History can be taught without enshrining every actor in our physical landscape.

We can remember Kotoka in history books, in academic discourse, in balanced curricula, without making his name the banner under which visitors and returning citizens enter our nation.

If we truly value democracy and the legacy of leaders like Nkrumah, as we say we do, then it’s time to align our symbols with those values.

Renaming Kotoka International Airport isn’t an erasure of history; it’s an affirmation of the Ghana we want to be: democratic, consistent, purposeful, and clear about who we honour and why.

If we can’t commit to that, then perhaps the confusion is real. And perhaps that’s the problem we need to confront.

Latest Stories

-

Prudential Bank champions tree crop investment at TCDA anniversary dialogue

9 minutes -

Roc Nation Sports International kicks off inaugural youth football tournament in Ghana

17 minutes -

‘Ghanaians are not genetically disorderly’ – Yaw Nsarkoh says consequences create order

40 minutes -

Electoral Cost Efficiency in Emerging Democracies: A Comparative Analysis of Cost per Voter in Ghana’s 2020 and 2024 General Elections

46 minutes -

BBC edited a second racial slur out of Bafta ceremony

1 hour -

Nigeria denies report it paid ‘huge’ ransom to free pupils in mass abduction

1 hour -

Gender Minister oversees safe discharge of rescued baby, settles bills and engages police on probe

2 hours -

Bawumia receives Christian Council goodwill visit after NPP flagbearer win

2 hours -

Afenyo-Markin urges Bagbin to summon Korle-Bu, Police, Ridge Hospitals over alleged denial of care to hit-and-run victim

2 hours -

Police reject GH₵100k bribe, arrest drug suspects with 209 slabs

2 hours -

Declare galamsey child health emergency – Pediatric Society to President Mahama

2 hours -

Finance minister lays Value for Money Office Bill before parliament

3 hours -

Stop illegal mining before treating the water – Awula Serwaa tells government

3 hours -

Christian Council warns prophets against fear-mongering, cites criminal liability

3 hours -

‘How can the same God reveal different outcomes?’ – Christian Council questions conflicting prophecies after NPP primaries

3 hours