Over the past few weeks, as the scale of the Covid-19 pandemic has become clearer, journalists, politicians, and economists have all made analogies to World War II. The scope of the challenge and the scale of economic dislocation invite these comparisons, as does the experience of shared sacrifice to combat a common enemy.

World War II offers valuable lessons for the current moment. But when many people picture the World War II economy, they’re thinking about how it operated by 1944 and 1945, when early problems had been solved and war production was at its peak.

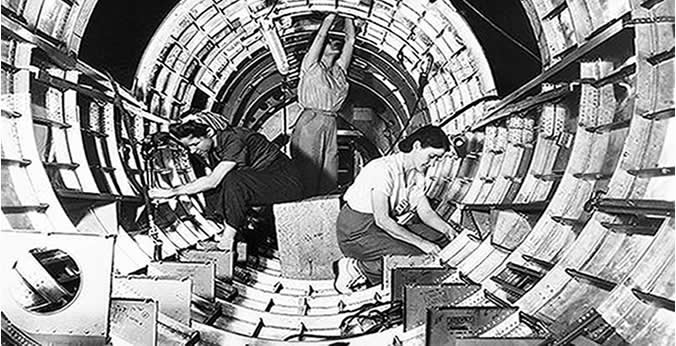

By then, industries large and small had joined the war effort: Washing machine manufacturers made artillery shells. Vacuum cleaner companies made bomb fuses. Tanks, airplanes, and anti-aircraft guns rolled off assembly lines that had once produced automobiles. American industry produced more than 96,000 planes in 1940 alone — a 26-fold increase over the 3,611 airplanes produced in 1940. An official military history credits American war production in its heyday with “virtually determining the outcome of the war.”

The current state of the coronavirus pandemic, though, is far more similar to the dark months after Pearl Harbor, when US leaders faced the daunting task of transforming the US economy virtually overnight, than it is to those triumphant final years.

Then as now, every day mattered. In the first months of 1942, top US officials feared that due to lack of equipment, America might lose the war before it got a chance to start fighting it. Their primary goal was transforming the economy as fast as possible.

“It was plain that all our plans would have to be revolutionized to meet the immediate necessities of a crisis as explosive as the bombs dropped on Pearl Harbor,” Donald Nelson wrote in Arsenal of Democracy. “It was no longer a question of guns and butter; the guns had to come first.”

Their experience still has lessons for policymakers today. Here are five of them.

1) Centralize and coordinate the government’s purchases of medical equipment, including personal protective gear

Without effective coordination, states and the federal government have entered bidding wars for desperately needed medical equipment. Shipments to states have been confiscated, prompting elaborate schemes like Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s efforts to get 1 million N95 masks delivered to Massachusetts. Chaos reigns as hospitals try to sort through the confusion of disrupted supply chains. President Trump insists that the federal government is “not a shipping clerk,” but in fact such coordination is precisely the federal government’s role.

The US faced a similar problem during World War I, when purchasing was decentralized. Different branches of the military, including numerous departments within the Army, competed with each other in bidding for contracts. This led to production delays and increased prices for critical supplies.

In World War II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the War Production Board. Decisions about what equipment was needed were made by the military, but the board oversaw and coordinated all war production. Its initial role was to get production going in sufficient, previously unthinkable, quantities and to arrange new supply chains to ensure materials ended up in the right hands.

For relatively simple production orders, the board publicized production requirements for the goods it needed and facilitated matching products with interested firms. The more complex and difficult orders were sent to the large, established firms with the greatest expertise in relevant production processes.

But the board’s role did not diminish once production got going. Rather, its focus changed to ensuring that scarce resources were being allocated optimally. Since it takes time for suppliers to expand production to meet demand, ramping up war production so quickly led to short-run scarcity.

The War Production Board was subject to both extensive public scrutiny and congressional oversight from the Truman Committee. Its appeals board heard complaints from business and labor leaders, members of Congress, and state and local politicians.

Because requirements were determined by the military, procurement decisions were largely apolitical. Researchers Paul Rhode, James Snyder Jr., and Koleman Strumpf found no evidence that World War II contract placement was systematically biased by political factors.

There are clear parallels to today’s war against the coronavirus. Without a clear centralized authority to place orders for critical medical equipment and personal protective equipment and to distribute finished products where they are most needed, the US risk a muddle of delays, inefficiencies, and needless price increases like those faced in WWII.

Dramatically increasing the available supply of testing, protective gear, and medical equipment will reduce the incentive for politically motivated allocations of equipment. Vigorous oversight from both Congress and the media, a transparent process for dispute resolution, and insulation from political pressure — ideally drawing on the judgments of medical and public health professionals — can help ensure that coordination of procurement benefits all states and localities during this crisis.

2) Repurpose existing institutions and take advantage of existing expertise

After Pearl Harbor, policymakers faced the need to transform the economy at a rapid pace. American policymakers feared the war could be lost before it had fully begun, so speed was paramount. One key element of the transition to a wartime economy was policymakers’ decision to transform existing institutions rather than create entirely new ones.

War Production Board Chair Donald Nelson left purchasing and procurement decisions in the hands of the armed forces, using the board to manage and coordinate. This was one of his most controversial decisions, but it was the right choice — at least for the initial phase of the war — for two reasons.

First, in 1942 as in 2020, every day mattered. Keeping purchasing and procurement in the hands of the agencies that had previously made these decisions saved precious time and allowed production to ramp up faster.

Second, only trained military officers had the expertise needed to evaluate whether specialized products such as airplanes, tanks, and radar met quality standards and fulfilled military needs. Nelson recognized that a civilian agency could not match the military’s expertise in determining such technical details.

Depression-era unemployment offices were also repurposed for the war. As unemployment fell sharply in the early 1940s, the US Employment Service pivoted from coordinating services for the unemployed to matching workers to war production jobs, helping employers find replacements for workers entering the military.

The lessons for today are clear: While the US needs central coordination for purchasing key equipment, specific procurement decisions — the specifications and requirements for medical equipment, as well as decisions about how much medical equipment is needed — must remain in the hands of medical professionals.

Local unemployment offices around the US are still well suited to help respond to the crisis, especially if the government works to expand their administrative capacity. They can contribute in many ways, such as administering furlough insurance for workers whose jobs are temporarily suspended or helping coordinate increased labor for key industries and labor-intensive pandemic response work, such as large-scale testing and contact tracing.

3) Availability of materials is a key constraint

During World War II, strategic materials, not labor or manufacturing capacity, proved to be the binding constraint on US wartime production.

That is likely to be just as true today. Constraints on manufacturing capacity are orders of magnitude less severe now than in WWII. More than $100 billion of military contracts were placed in the first six months of 1942, compared to $20 billion in defense contracts over all of 1941 and a 1941 GDP of $129 billion. Production capacity initially fell far short of what was needed for the war effort, even with extensive conversion of civilian manufacturing capacity. Today the US needs vast increases in the production of medical equipment, particularly ventilators, personal protective equipment, and test kits, but the total volume of equipment needed is significantly less than a full year’s GDP.

Similarly, given the recent explosion in unemployment claims in the wake of the crisis, constraints on labor capacity are less immediate. Unless the pandemic is left unchecked, growth in the number of available workers should outpace the number of workers sickened by Covid-19 infections. The point at which labor force capacity would become a binding constraint is far past the point at which the health care system would be overwhelmed — a situation that must be avoided at all costs.

The US needs to worry about materials availability first and foremost. Although the country avoided nationalizing most industries during WWII, the federal government did take direct control of the production of rubber and metals.

4) The crisis itself creates strong incentives for manufacturing firms to produce critical equipment

The US did not nationalize major industries to achieve its World War II production miracle. US war production relied primarily on manufacturing by private firms, as the war aligned manufacturing firms’ incentives with those of the nation.

The Defense Production Act is a good mechanism for mobilizing industry — indeed, it was written when the experience of World War II was recent memory — and should be used aggressively as needed.

But with clear and effective federal leadership, its necessary application may be narrow. There are other ways to push industry to produce needed supplies. A government guarantee to buy all medical equipment meeting stated specifications and produced by specified dates at a set price, combined with the incentives provided by the crisis itself, would provide enough incentive for most firms. Voluntary agreements authorized under the DPA would allow firms to cooperate effectively and scale production faster, mimicking the inter-firm cooperation that defined the home front during World War II.

A number of private firms are already converting their production lines to key equipment, from small distilleries making hand sanitizer to Ford Motor Company’s production of ventilators, even in the absence of clear leadership and communication from the federal government.

In WWII, most US firms faced a choice between sitting idle —a home appliance producer cannot produce appliances if it cannot acquire the metal needed to make its products — and participating in war work. The government’s control of raw materials created the incentives for firms to convert voluntarily: Firms that volunteered for war production were able to acquire inputs, while other firms were not.

There was also an overarching incentive for war production: The sooner firms produced the needed materials, the faster the war could be won, and the sooner everyone could get back to real life. That same overarching incentive exists today, and it is powerful.

Lockdowns, quarantines, and abruptly rising unemployment have sharply reduced demand for many goods. Manufacturing firms in sectors that now face reduced demand, such as car manufacturing, have every incentive to volunteer to produce needed medical supplies as soon as a centralized process for placing orders can be put into place. What’s needed is a mechanism for matching production needs to firms’ manufacturing capacities.

During World War II, when multiple manufacturers expressed interest in producing a good, often contracts went to all of them because demand was so high. Then as now, overproduction is a problem the US can only dream of facing. Any excess ventilators or protective equipment left over at the end of the pandemic can be stockpiled or sold.

In 2020, the key strategic materials are different: chemical reagents needed for testing, synthetic materials capable of blocking airborne particles, and so on. Ensuring the availability of these materials must be a top priority. The government must act to build adequate supply chains for scarce raw materials, particularly the specialized paper pulp used in the production of PPE.

5) The evidence supports a strategy of relief now and stimulus after the pandemic

A key concept in macroeconomics is the fiscal multiplier, which measures how much GDP responds in proportion to a change in government spending or taxes. If the fiscal multiplier is large, spending increases or tax cuts will be an effective way to stimulate the economy, but if the multiplier is small, government spending or tax cuts will be inefficient stimulus.

Recent research in economics has emphasized that the fiscal multiplier varies significantly depending on context. First, the multiplier will be higher on some kinds of government spending or tax cuts than on others, often depending on who benefits. Second, recent research has emphasized state dependence in the multiplier, or the idea that the fiscal multiplier is larger when the economy is in a recession. Although the US has entered a (severe) recession, the multiplier is likely to be smaller than usual during this pandemic, not larger. The country can expect to see a significantly larger fiscal multiplier when the pandemic ends — whenever that may be.

My research found that the fiscal multiplier in WWII was much smaller than the typical multiplier because the savings rate was so high during the war. Many products, particularly durable goods, were not available for purchase during WWII because they were not produced at all. Consumer spending rebounded strongly after the war ended, particularly on goods, such as cars and appliances, that were not available during the war.

The experience of WWII suggests that when consumption options are significantly restricted, people may spend a smaller share of income than in other times. Specifically, the closest substitute for buying a specific good now is buying that good in the future, when it is available again, rather than buying another good. The extreme uncertainty of the current situation may also depress the multiplier, since people will delay making decisions and larger purchases.

Today, significant sectors of the US economy have ground to a halt, particularly the travel, arts, and restaurant industries. As in WWII, the ordinary lives of millions of Americans have been abruptly transformed. Significant portions of people’s regular consumption baskets are unavailable, even though no formal rationing has been enacted. So, as in WWII, the multiplier on relief spending may be lower than in a “normal” recession.

The evidence from World War II strongly backs up the paradigm that policy should focus on relief now and stimulus later. Targeting relief funds may help increase the multiplier to the extent that most relief funds are used to buy basic necessities. People who lose all or most of their income in this pandemic recession will be more likely to spend on necessities rather than saving, which would increase the fiscal multiplier. However, perfect targeting may be difficult to achieve quickly.

Further evidence from late in the Great Depression suggests that fiscal stimulus may be particularly effective after a long period of downturn, as it can support pent-up demand. This suggests that policymakers should focus on relief for as long as the pandemic continues, including with further rounds of such relief as needed, but then be sure to follow relief with broad-based stimulus to help the economy rebound.

Latest Stories

-

We have enough funds to pay accruing benefits; we’ve never missed pension payment since 1991 – SSNIT

13 mins -

Let’s embrace shared vision and propel National Banking College – First Deputy Governor

49 mins -

Liverpool agree compensation deal with Feyenoord for Slot

56 mins -

Ejisu by-election: There’s no evidence of NPP engaging in vote-buying – Ahiagbah

1 hour -

Ejisu by-election: Independent ex-NPP MP’s campaign team warns party against dubious tactics

1 hour -

ZEN Petroleum supports Tse-Addo Future Leaders School

2 hours -

NPP must win back Adentan seat in 2024 polls – Obeng Fosu

2 hours -

PPA Clarification: The dark side of the World Bank’s ‘giveaways’ in Ghana by Bright Simons

3 hours -

Blinken says China helping fuel Russian threat to Ukraine

4 hours -

MHA declares May as Purple Month for Mental Health Awareness

4 hours -

WAEC arrests former headmaster over illegal students registration

5 hours -

MeToo founder Tarana Burke defiant after Harvey Weinstein ruling

5 hours -

Be alert, insist on decent messages – Dwumfour tells media

5 hours -

Father jailed 10 years for burning daughter’s genitals with hot cutlasses

5 hours -

I aim to help Ghana produce world-class athletes – Asamoah Gyan

5 hours