Audio By Carbonatix

Yesterday, I read the “exposure draft” of the Bank of Ghana’s Guideline for the Regulation and Supervision of Non-Interest Banking.

The first thing that struck me is that the central bank’s strategic decision to rebrand “Islamic Banking” as “Non-Interest Banking” (NIB), while understandable as a bid to avoid the kind of needless controversy sparked in Nigeria in 2011 when the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) first introduced Islamic Banking, has ended up creating unnecessary technical confusion.

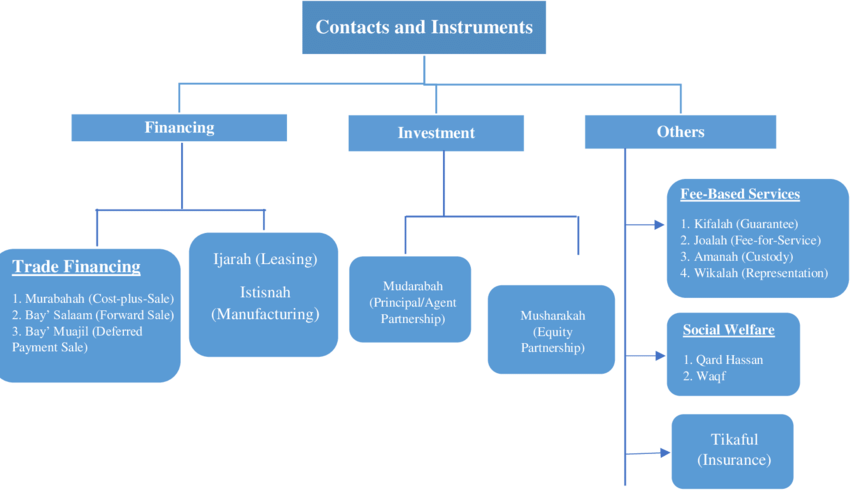

Source: Nafiz (2019)

The Bank of Ghana (BoG) sets out to strip religion from so-called “non-interest banking” by placing a prohibition on religious symbolism (Paragraph 85) but then proceeds to demand that all participants in the proposed non-interest banking industry also adhere to AAOIFI standards (Paragraph 6).

AAOIFI, founded in Bahrain in 1991, means Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI). The profound market identity crisis should be obvious to all.

The governance structure that the BoG has ended up proposing is bifurcated between an internal Non-Interest Banking Advisory Committee (NIBAC) and an external Non-Interest Financial Advisory Council (NIFAC). A “clash of standards” between secular prudential norms and religious stipulations is inevitable as I will explain shortly.

Furthermore, the “Windows” model (Part IV), which allows conventional banks to also provide Islamic Banking products, could easily, because of this double-personality approach, end up creating risks of cross-contamination and regulatory arbitrage.

One way this could happen is where conventional banks exploit the fungibility of capital to leverage non-interest banking tax advantages (which may be required for certain purposes as I will explain to avoid double-taxation), or indeed any other regulatory concessions, without adhering to the spirit of risk-sharing that defines the very foundation of non-interest banking.

A bit of history

The Exposure Draft of December 9, 2025, arrives nearly a decade after the passage of the Banks and Specialised Deposit-Taking Institutions Act, 2016 (Act 930). Act 930 was born following the microfinance crises of the early 2010s to provide a holistic framework for risk management across the entire banking landscape.

The whole logic of Act 930 is rooted in the concept of “intermediation”, that is to say, the taking of deposits and the lending of funds for interest.

The first few paragraphs of the Exposure Draft are very explicit about its objective: “to meet the growing interest from individuals, banks, and financial institutions for the introduction of Non-Interest Banking (NIB) products and services”. It should be obvious that what is being introduced is not some marginal footnote to how banking is done in Ghana but a truly parallel regime.

To navigate this inherent tension, the BoG has adopted a strategy of playing with words. It starts by stripping the term “Islamic” from the regulation, thereby hoping to secularize the mechanism of the finance while retaining its substance. All the while trying to make it look as if “interest” has always been a flexible notion in mainstream banking in Ghana and there is no real need to resort to Islamic principles to get to “non-interest banking”.

This is evident in the Title and Paragraph 1, which refer strictly to “Non-Interest Banking”. My goal in this essay is to show that this rebranding is superficial.

Paragraph 5(k) explicitly anchors the entire guideline in the standards of the Accounting and Auditing Organisation of Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI). As mentioned earlier on, and shall be elaborated further, the BoG finds itself grappling with a fundamental contradiction: the regulator insists the system is “Non-Interest” (a secular, descriptive, definition) while legally binding it to “Islamic” (a religious, prohibitive, definition) standards.

The definitions lose their moorings

Paragraph 7 serves as the glossary of the regime. It defines “Non-Interest Banking” as business consistent with “Non-Interest Banking and Finance (NIBF) sources”. This is circular logic. The definition relies on the very term it seeks to define. More critically, the definitions of the specific contracts are ALL derived directly from classical Islamic Fiqh (jurisprudence):

- Mudarabah is defined as a partnership between rabbul maal (capital provider) and mudarib (manager).

- Gharar is defined as excessive uncertainty.

- Maysir is defined as gambling.

What at all is going on here?

These terms have no foundation in English Common Law or Ghanaian Statutory Law. By importing these Arabic legal terms into a “Non-Interest” guideline without a primary “Islamic Banking Act” to define them at a statutory level, the BoG leaves their interpretation open to the secular courts.

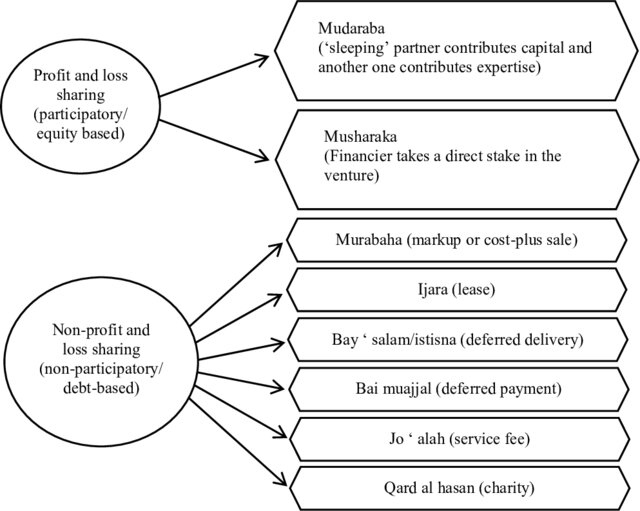

Source: Beloucif et al (2017)

What happens when a dispute arises regarding a Mudarabah contract? I insist that all a Ghanaian judge can do is look to the definitions in Paragraph 7. However, Paragraph 7 refers to “established NIBF sources.” If the judge consults AAOIFI (as mandated by Paragraph 5), they are effectively applying religious law. Are they equipped to do it? Or are we going to have a specialised bench to support this abrupt legal reality? If the Judges choose instead to apply the Companies Act 2019 (Act 992), they may view the arrangement as a simple limited liability partnership. That could potentially void the specific risk-sharing provisions that make the arrangement Shariah-compliant. And for what? Avoidance of even the most minimal controversy?

Regular readers of this website would immediately recognise the “katanomics” syndrome at work. Without clear policy rationales, Ghana is already rushing to create legally binding precepts. Let’s look at some of these issues in detail.

The Prohibition of Religious Symbols (Paragraph 85)

Paragraph 85 represents the apex of this regulatory confusion. It mandates:

“For the avoidance of doubt, the registered or licensed name of a NIBI shall not have any religious connotation, symbol or any other related expression or derivation, as may be determined by the Bank.” 1

Behold a severe “Signaling Problem.” Islamic banking relies heavily on trust and identity. The target demographic (the pious unbanked) needs assurance that the bank is not merely a conventional bank disguised as a charity. They look for signifiers like “Islamic,” “Shariah,” or symbols like the crescent or specific calligraphic styles. By banning these, the BoG raises the Information Asymmetry costs for consumers.

Let us remember that it is a competitive market. Islamic Banking (or call it “Non-Interest Banking with Islamic Characteristics”) places fetters on bankers. The only way for operators to regain some footing in the market is to draw strongly on their religious differentiation by targeting customers making decisions on the strength of certain ethical and identity drivers.

It is not as if we haven’t tried this kind of loose, hollow, Islamic banking approach before. Under the Wampah administration, a group of Saudi investors were licensed to set up Makkah Bank. After much huffing and puffing, the endeavour came to nought and the license was pulled in 2016. We have also had Islamic microfinance banks like Salam and GMIF try to penetrate and fail. A country with a national learning tradition would draw on all these lessons.

Confusing “Riba” with “Interest”

Paragraph 7 states: “Riba means any predetermined, fixed or guaranteed interest… For the purposes of this Guideline, it is synonymous with ‘interest’…”.1

This statutory equation of Riba with Interest is a dangerous oversimplification that creates regulatory arbitrage risks. In Islamic jurisprudence, Riba is broader. It includes Riba al-Fadl (usury of excess in commodity exchange).

If Riba is legally defined only as interest, a bank could theoretically structure a transaction that involves an unequal exchange of gold or currencies (which is classically Riba) but does not involve “interest” in the conventional sense. Under the Draft’s definition, this might be permitted.

Conversely, the strict ban on “interest” might create friction with the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA), which treats interest as a specific deductible expense. If the non-interest banking institution (NIBI) claims it does not pay “interest” but rather “profit,” the GRA may deny tax deductibility, making NIB products 25 to 30% more expensive (the corporate tax rate) than conventional loans. This is precisely the tax treatment complexity I mentioned earlier.

Compliance Structuring

The Exposure Draft creates two new bodies:

- Non-Interest Banking Advisory Committee (NIBAC): An internal body within each NIBI (Paragraph 69).

- Non-Interest Financial Advisory Council (NIFAC): An external advisory body to the Bank of Ghana (Paragraph 80).

Paragraph 69 mandates that every NIBI must have a NIBAC. Paragraph 73 states that “Remuneration for NIBAC shall be determined by the Board of the NIBI.”.

The NIBAC is responsible for ensuring the bank’s compliance with NIB principles (Paragraph 74). Essentially, they are the “religious auditors.” However, they are paid by the very Board they are supposed to police. This creates a classic principal-agent problem. In a drive for profitability, a Board might pressure the NIBAC to approve a borderline product (e.g., a Tawarruq facility that closely mimics a personal loan). Since the NIBAC members serve renewable terms (Paragraph 73), they have a financial incentive to be “business-friendly” rather than strict.

A similar bizarre thing the Exposure Draft does is create a bizarre judicial role for the NIBAC. Paragraph 55 states: “The NIBI shall resolve such disputed matters using the NIBAC as an internal adjudicatory structure.” This violates the principle of natural justice, nemo judex in causa sua (no one should be a judge in their own cause). If a customer sues the bank claiming a product is Haram (impermissible) and void, the case is heard by the NIBAC (the very body that approved the product in the first place, according to Paragraph 47). This structure stands a high risk of being struck down by Ghana’s Commercial Courts as unfair, creating legal friction.

Finding enough professionals in Ghana who are skilled in both conventional banking compliance and Islamic jurisprudence is another issue. But there are enough players springing up to fill the gap (see below, for example), so I won’t dwell too much on that issue.

Paragraph 80 establishes the NIFAC to advise the Bank of Ghana. Paragraph 51 states that products require “satisfactory recommendation by NIBAC and NIFAC.”

The inevitable outcome, whether BoG strategists want to admit it publicly or not, is a “Supreme Shariah Board” within the secular Central Bank. If NIFAC rejects a product based on religious reasoning (e.g. by flagging a contract as containing Gharar), the Bank of Ghana is enforcing a religious edict.

In a secular state like Ghana, without explicit accommodation created by substantive law (as opposed to the legal precepts embodied in the proposed guidelines) this opens the BoG to administrative law challenges. Can a secular regulator deny a license based on a theological interpretation without an amendment to its enabling law?

The issue of multiple Islamic schools of jurisprudence is, however, outside the scope of this short essay.

“Window” Segregation

Paragraph 62 mandates: “The NIBI shall establish a system that ensures that there is no commingling of funds relating to the NIBI business with the conventional business activities of the entity.”

Paragraph 63 reinforces this with the “Non-Interest Finance Fund (NIFF)” requirement.

However, Paragraph 60 allows the window to “operate using the existing facilities or branch network of the conventional bank.” We must bear in mind that:

- While a bank’s ledger may be separate (Par 67), the cash is physically commingled at the branch level. When a customer deposits cash into an NIB account at a conventional branch, that physical cash goes into a safe mixed with conventional deposits. It is only separated accounting-wise later.

- In a liquidity crisis, money is fungible. If the conventional parent bank faces a run, will it strictly ring-fence the NIFF? Or will it “borrow” from the NIFF to meet conventional withdrawal demands, perhaps using an internal Qard (loan) mechanism? History in other jurisdictions suggests that without distinct legal entity status (subsidiarization), commingling is inevitable during stress events.

- If the conventional corporate parent is involved in financing a brewery or a pig farm (activities prohibited in NIB), the “purity” of the NIB window is conceptually compromised. The Draft attempts to solve this with “Service Level Agreements” (Paragraph 61), but an SLA cannot cure the fact that the ultimate beneficial owner of the NIB profit is a conventional, interest-based shareholder base.

Is there a Fintech Loophole (Paragraph 46)

Paragraph 46 imposes a draconian restriction on Fintechs:

“Any FINTECH company that develops… non-interest financial product shall enter into a prior written agreement with a licensed NIBI… the NIBI must assume responsibility…”

This clause effectively kills independent Islamic Fintech innovation in Ghana.

- It forces agile startups to partner with incumbent banks (NIBIs). The NIBIs, acting as gatekeepers, can charge rent-seeking fees for this “sponsorship.

- Mobile Money (MoMo) is the driver of inclusion in Ghana. By tethering NIB MoMo products to the heavy compliance infrastructure of a bank (Paragraph 46), the Exposure Draft increases the cost of delivery.

The Crux of the Matter

The main point is that many of these issues have been thoroughly addressed in proper, fully-fledged, Islamic Banking jurisdictions in places like the Gulf. One should not reinvent the wheel. But embracing mature jurisprudence requires open admission and clear messaging.

We just have to deal with the fact that in modern times, the only tradition that has developed non-interest banking to a granular level is the Islamic tradition. Pretending otherwise just leads to confusion.

It is true that a millennium ago, there were advanced Christian non-interest banking systems. The church had a ban on “usury”, which though meant “excessive interest” soon became synonymous with interest itself. In fact, this history is intertwined with the history of how Jews became such prominent financiers in the modern era.

When Pope Innocent III banned Jews in Europe and elsewhere in Christendom from most professions and trades in 1215, by edict of the 4th Lateran Council, he permitted them the practice of usury. Though Judaism also frowns on usury, Jewish theologians had tended to restrict it to Jew-on-Jew usury. Hence, Mediaeval Jews could lend liberally to Christians, whilst Christian financiers, like the Knights Templar, had to contend with more restrictive instruments like Bills of Exchange.

But by the time of the reformer Calvin, the Christian ire against interest had started to dissipate. By the Enlightenment, the notion of “Christian Finance” was more or less fringe. Thus, since 1600, much of the texture and logic of how non-interest banking should work has been developed within Islam. Any attempt to deny this reality simply leads to confusion.

Frictions over Essences

For example, Paragraph 51 lists the permissible contracts in the non-interest banking regime. Each introduces specific frictions if naively and simplistically overlaid on Ghana’s secular commercial law.

Murabahah (Cost-Plus Financing) versus The Loans Act

- Paragraph 7 defines Murabahah as a “sale contract whereby the institution sells to a customer a specified asset… at… cost price and an agreed profit margin.” In secular law, this is a pure and simple “Sale of Goods.” In banking law (Act 930), banks are generally prohibited from trading in goods (buying and selling inventory) to prevent commercial risk.

- If Murabahah is a sale, it attracts Value Added Tax (VAT) and National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL). A conventional loan attracts zero VAT on the principal or interest. Thus, without a specific exemption from the GRA, a Murabahah auto-finance facility involves the bank buying the car (VAT paid) and selling it to the customer (VAT paid again). This double-taxation makes the product about 30 to 40% more expensive than a conventional loan.

- The Exposure Draft is silent on tax neutrality precisely because it wants to pretend that the whole thing is a simple grafting on the existing secular banking system.

Ijarah (Leasing) and Asset Liability

- Paragraph 7 defines Ijarah as a lease of usufruct. In a true Ijarah, the bank (Lessor) owns the asset and bears the risk of ownership (destruction, major maintenance). In a conventional finance lease, risk is transferred to the lessee.

- If a non-interest banking institution (NIBI) owns a fleet of cars leased to customers, and one car is involved in a fatal accident due to a brake failure (maintenance issue), under Ghanaian tort law, the owner (the Bank) could be liable. Conventional banks avoid this via the pure lending model. NIBIs, by being forced to “own” the asset to satisfy Shariah (Paragraph 3), expose their balance sheets to operational and vicarious liability risks that Act 930 capital buffers were not designed to absorb.

Mudarabah/Musharakah and Deposit Protection

- Paragraph 7 defines these as partnerships where “loss is borne by the fund/capital provider” (the depositor). Ghana’s Deposit Protection Corporation (GDPC) insures deposits. But Mudarabah investment accounts (PSIA) are risk-bearing equity-like instruments (see Paragraph 91).

- If the GDPC guarantees these accounts, it violates the Shariah principle of risk-sharing (making the product Haram). If the GDPC does not guarantee them, NIBIs face a massive competitive disadvantage. Why would a customer deposit money in an NIBI (risk of loss) when a conventional bank offers a state guarantee?

- The Draft proposes a “Profit Equalisation Reserve” (PER) and “Investment Risk Reserve” (IRR) in Paragraphs 95 to 96 to “mitigate volatility.” This is an accounting smoothing mechanism. However, it doesn’t solve the statutory guarantee issue. Paragraph 91, in its current form, explicitly forces the bank to transfer the risks to its depositors. In a systemic crisis, this clause will likely be politically unenforceable, forcing a government bailout and destroying the theoretical model.

A Potential Liquidity Management Vacuum

Paragraph 125 states:

“In the management of liquidity, NIBIs shall be prohibited from investing in interest-bearing securities or activities.”

It bears emphasising the following.

- The primary liquidity management tool for banks in Ghana is the Government of Ghana Treasury Bill (T-Bill) and BoG Bills. These are interest-bearing, haram, and incompatible with Shariah-compliant finance.

- NIBIs are thus legally barred from the safest, most liquid asset class in the country.

- Without clear policy intervention, NIBIs must hold excessive amounts of physical cash (which earns zero return) to meet the Capital Reserve Ratio (CRR) and unexpected withdrawals. This “cash drag” significantly depresses their Return on Equity (ROE), making them structurally less profitable than conventional banks.

- And all because the country has simply, in classic Katanomic fashion, decided to erect legal structures in a policy vacuum. The Draft doesn’t even bother to delve into issuance of Sukuk (Islamic Bonds) or a Shariah-compliant Liquidity Facility by the Central Bank. Without these, how exactly is a non-interest banking regime meant to deal with systemic risks? NIBIs are being condemned to be permanently “long cash” and unable to sterilize excess liquidity, or “short cash” and unable to access the repo window (which is interest-based).

Let’s even talk about Capital Adequacy

Paragraph 122 states CAR shall be calculated “consistent with the prevailing requirements applicable to conventional banks.”

The twist here is that Conventional Basel II/III rules don’t perfectly fit NIB. For Musharakah (partnership), the risk weight should theoretically be 300 to 400% (like equity). If the BoG applies standard risk weights (100% for corporate claims), it under-capitalizes the risk. If it applies equity risk weights, it makes the NIB model capital-inefficient. The Draft leaves this ambiguity to “directives issued by the [Central] Bank,” creating regulatory uncertainty.

All because someone is refusing to accept that they are introducing a parallel, religiously grounded, banking regime that requires its own end-to-end policy infrastructure to be relevant and meet its objectives of financial inclusion. Literally katanomics on steroids.

Always learn from others

Many countries in the world, including even some in Europe, have full-blown Islamic Banking regimes. Everyone knows what it is and how it differs from conventional banking. By being forward and plain about Ghana’s interest in introducing Islamic Banking, we can more frontally deal with issues.

Nigeria’s decision to embrace the “non-interest” jargon to evade Christian sensitivities did not really work out. It did not ablate the prejudices.

- Nigeria faced regional concentration issues. The initial NIBs (like Jaiz Bank) were viewed as “Northern Banks.”

- Paragraph 140 of the Exposure Draft is a tacit admission of the risk of “Zongo Banking” (i.e. NIBIs clustering in Muslim-majority communities like Nima, Mamobi, and major towns in the Northern Regions) and fail to integrate into the national financial grid.

- Here is the bare fact: In Nigeria, it took over a decade for NIB to gain mainstream traction. The “Non-Interest” label may have helped with legal passage but hindered marketing. In Ghana, we don’t even seem to be planning to introduce a comprehensive legal framework. Ghana’s strict ban on religious symbols (Paragraph 85) is even more aggressive than Nigeria’s. Anyone can guess the outcome: Ghana will likely face an even slower adoption curve.

Nigeria also struggled for years with the double-taxation of Murabahah transactions. It required specific amendments to tax laws to treat non-interest banking transactions as “financing” rather than “trading” for tax purposes.

The Exposure Draft mentions Act 930, Act 992 (Companies), Act 774, Act 1032, Act 1044 (AML). But it conspicuously fails to reference the Income Tax Act or Value Added Tax Act. This silence indicates that the critical work of tax harmonization has not yet been done. Without it, the Nigerian lesson suggests the sector will launch but remain stagnant and uncompetitive.

Some ideas are out of context

A number of paragraphs had me scratching my head as to whether serious socioeconomic and fiscal environment context analysis was commissioned by BoG strategists.

For example, Paragraph 54 discusses late payment issues, a common challenge facing banks in Ghana. Hear:

“In instances where late payment penalties are levied… the NIBI is expressly prohibited from deriving any financial benefit. Such penalties must be… disbursed in their entirety to charitable causes.”

Seriously? Yes, Shariah aims to prevent one from benefiting from the pain and misery of others. Ordinarily, someone struggling to keep up with their loan payments shouldn’t be knocked further. But Ghana is a country of all kinds of “settings entrepreneurs” who are known to abuse bank facilities. One has to knit and weave skillful Shariah-compliant penalty regimes to deal with it.

How the BoG has drafted the provision simply removes the economic incentive for the bank to enforce timely repayment. In a high-inflation environment like Ghana (often >20%), time is money. A conventional bank charges penalty interest to cover the cost of funds. An NIBI, in BoG’s current vision, is expected to collect the penalty and then gives it all away!

We have to understand that Borrowers are rational. If they hold a loan with Ecobank or Stanchart (accumulating penalty interest) and a facility with an NIBI (where penalty goes to charity and therefore incentive to collect is lower), they will prioritize paying Ecobank. The NIBI becomes the creditor of last priority. This section structurally degrades the credit quality of NIBIs and needs extensive rethinking within the Shariah jurisprudence tradition.

Paragraph 109 sums up a central confusion

It says:

“Where there is a conflict between local and international… standards, the provisions of the local standards issued by the Institute of Chartered Accountants (Ghana) (ICAG) shall prevail…” 1

MeanwhileParagraph 5 requires overarching adherence to AAOIFI, a foreign standard. Yet, here is paragraph 109 requiring adherence to ICAG (which adopts IFRS).

- AAOIFI and IFRS conflict fundamentally on the treatment of Profit Sharing Investment Accounts (PSIA). AAOIFI treats them as “quasi-equity” (off-balance sheet or distinct equity line). IFRS 9 may force them to be treated as “financial liabilities” (deposits).

- If the NIBI follows ICAG (per Paragraph 109) and treats PSIA as liabilities, it may violate the Shariah requirement that capital must bear risk. The NIBAC (Paragraph 74) might then declare the bank non-compliant. The bank is trapped now, not so? It must either break secular accounting law or break religious law. The Exposure Draft provides no resolution mechanism for this specific clash. Because the BoG somehow thinks that it can muddle through the Double-Personality problem!

Another one: Paragraph 91

It says:

“The written notification shall expressly state that the NIBI shall not share in such losses, except where negligence… is established.”

- This relies on the “Negligence” loophole. In any investment loss scenario, a clever lawyer can argue “negligence” or “misconduct” by the bank management.

- Moreover, This shifts the burden of proof to the retail depositor, but also opens the door for class-action lawsuits. Every time an NIBI declares a loss on PSIA, it will face litigation claiming the loss was due to “mismanagement” (which shifts the loss back to the bank). This makes the NIB model highly litigious compared to the fixed-return conventional model.

Final Verdict

There are a whole host of issues around the prospects of Islamic Banking itself within our business environment that I touched on briefly on X (formerly Twitter) that I won’t go into here as my primary reason for writing this essay was to expose the katanomic confusions in the policy-regulation-law spectrum of the situation.

As it stands now, I would just summarise by saying that the Exposure Draft introduces high failure tolerances because of its fundamental IDENTITY CRISIS.

As structured in the Exposure Draft, the proposed non-interest banking regime is vulnerable to regulatory arbitrage (via the Windows model), legal friction (via the undefined status of Shariah contracts in secular courts), and cross-contamination (via fungible liquidity).

For the whole enterprise to succeed, the “Non-Interest” label must be supported by “Interest-Specific” legislation (examples: tax amendments and a Sukuk law) that openly acknowledges, if not embrace, the unique Islamic heritage, of this whole Shariah-compliant finance industry rather than simply obscuring its name. Islamic Finance has taken 1300 years to evolve into a set of rather specialised niches. There is no getting around that blatant fact.

Without these, the non-interest banking sector the BoG is ushering in with such aplomb in Ghana risks becoming a “zombie” industry, big on grammar and paperwork but functionally irrelevant, both in the Zongos and in the leafy suburbs of Ridge.

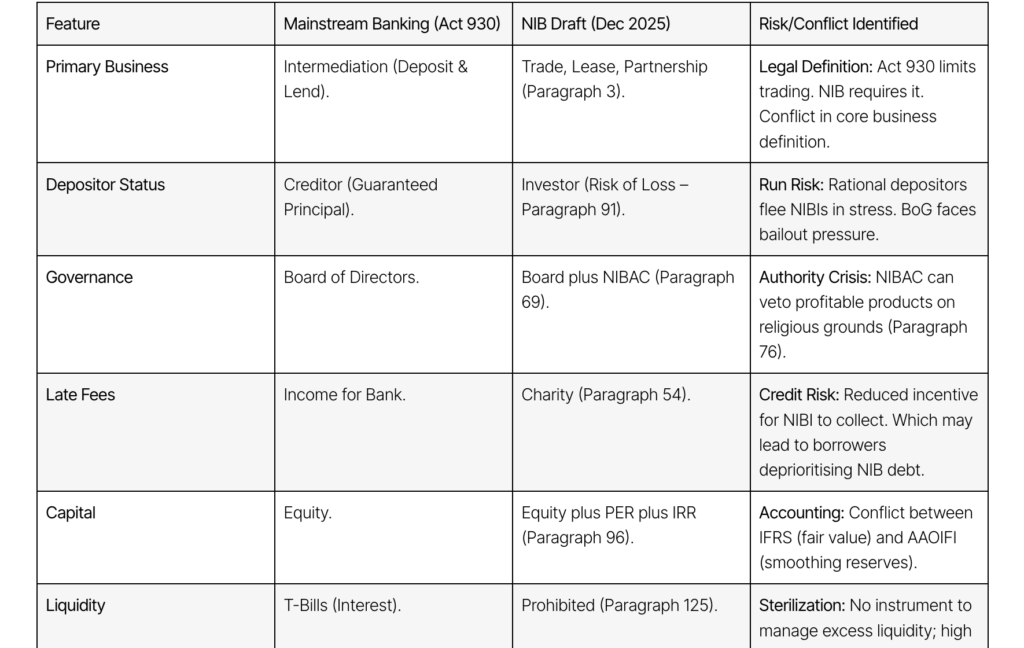

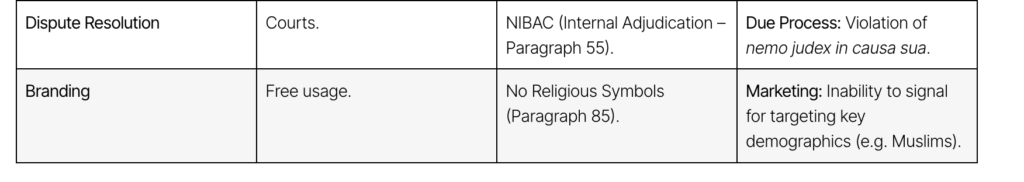

Appendix: Side-by-Side Comparison

The following table serves as a granular comparison between the existing mainstream banking framework and the proposed non-interest banking (NIB) regime, identifying specific friction points.

Latest Stories

-

Ghana International School and Coral Reef Innovation Africa sign landmark MoU to establish innovation center of excellence

3 minutes -

Ghana poised to lead Africa’s green aviation revolution, says GCAA Director-General

3 minutes -

Chinese dance group’s tour triggers bomb threat against Australian PM

14 minutes -

Senegal PM proposes doubling prison sentence for same-sex relations

16 minutes -

Clement Apaak defends dog and cat meat consumption, rejects health and ethical criticism

18 minutes -

Minority leader Alexander Afenyo-Markin urges government to enable, not control economy

18 minutes -

Mercy to the World scales up Ramadan feeding campaign, targets over 25,000 people

21 minutes -

Four arrested for posing as security operatives in illegal anti-galamsey extortion

21 minutes -

We want perfection in officiating – Kurt Okraku tells referees

36 minutes -

We’re not opposed to development; we are against illegality — Minority

37 minutes -

Residents of Sokoban wood village protest dusty road, cite rising respiratory cases

49 minutes -

Full text: Frank Annoh-Dompreh’s speech on defending constitutional governance and ensuring accountability in DACF use

50 minutes -

Minority vows to defend constitution amid DACF allocation dispute

50 minutes -

Emergency command centre needed to fix Ghana’s health response — Prof Beyuo

58 minutes -

Minority proposes automatic DACF allocation mechanism

1 hour