Audio By Carbonatix

When I arrived in Tanzania, I thought I knew what to expect. I’d been on election observation missions before. But this one turned out to be unlike anything I’d ever experienced.

Even before I unpacked, the signs were clear. X — what was once Twitter — didn’t work. International outlets like BBC and Al Jazeera were already reporting that major opposition figures had been disqualified from the race. The political field wasn’t just uneven; it was bare.

Key challengers, Tundu Lissu of Chadema and Luhaga Mpina of ACT, had been barred from running, leaving President Samia Suluhu Hassan virtually unopposed.

That first night in Dar es Salaam, I took a short walk along Kivukoni Front to sense the mood. No one — not the cobbler polishing shoes, the office workers heading home, nor the fish sellers by the roadside — would talk about the election. One security guard, barely whispering, told me he feared being attacked or abducted if he spoke his mind. Then, almost under his breath, he admitted he would have preferred the opposition.

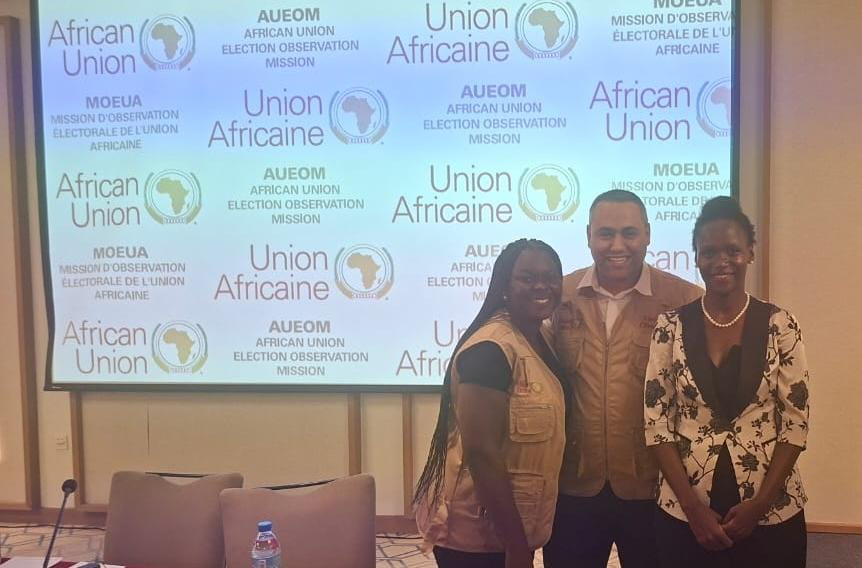

In the days leading up to the polls, our team of observers received the usual briefings — political context, dos and don’ts, red flags. We met civil society groups too, but they seemed unusually subdued. When I asked whether the atmosphere was fair and open, no one would answer directly. That silence spoke volumes.

On election day, I was stationed in Ugunja North, Zanzibar — beautiful and politically complex, with its own president, vice president, and house of representatives. There were two voting days: one for security officers on the 28th and the general vote on the 29th.

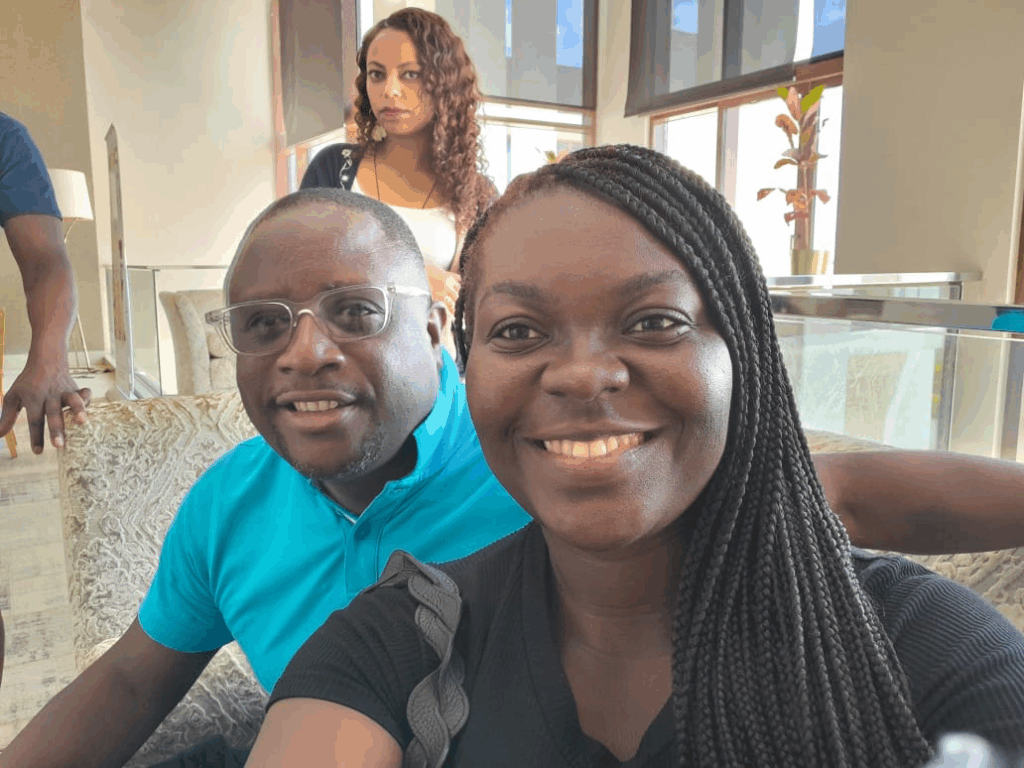

The morning began peacefully. My partner, Sidney from South Africa, and I moved from polling station to polling station — smiles, patience, calm. Democracy at work, or so it seemed.

Then, the mood shifted. Police and military patrols appeared everywhere. Around midday, reports trickled in of protests on the mainland — in Arusha, Mwanza, even Dodoma. Moments later, the internet went dark.

No WhatsApp. No Twitter. No news. Nothing.

A total digital blackout.

For us observers, it was like losing oxygen. We couldn’t communicate, report, or verify anything. We returned to our hotel in silence. Later, we learned through BBC and Al Jazeera that violence had erupted, with reports of deaths, roadblocks, and chaos.

By nightfall, a curfew was imposed. Offices closed, flights grounded, ferries halted. We were trapped — observers in a lockdown, watching democracy disappear.

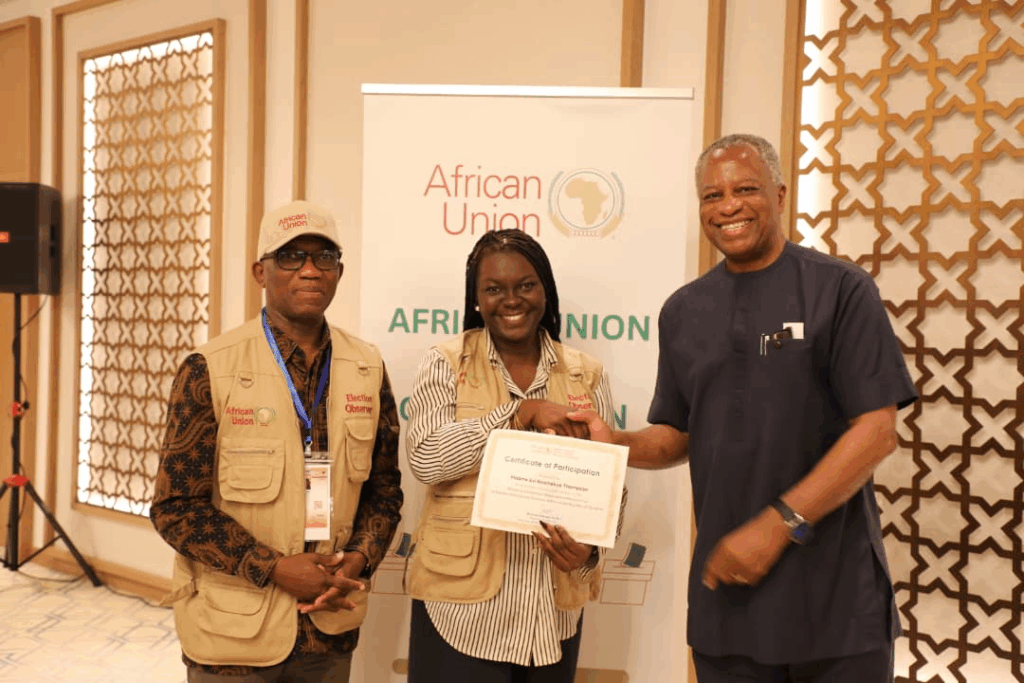

The uncertainty was suffocating. With no internet or updates, we relied only on our mission leads — H.E. Geoffrey Onyeama, former Nigerian Foreign Affairs Minister, and Thawanda from the African Union — to keep us informed.

We packed to leave, but the news came: no one was leaving Zanzibar. Ferries grounded. Flights cancelled. Mainland in turmoil. We had to check back into our rooms, unsure what would happen next.

That night, a few of us — Mihret from Ethiopia, Fardoso from Somalia, and Sidney from South Africa — gathered at the hotel restaurant. We sipped Zanzibar’s masala tea, trying to laugh through the anxiety. But the worry always returned. What if we never got out? What if our colleagues on the mainland were in danger?

Our unofficial team anchor, Esther Passaris, a Kenyan MP, remained calm, her quiet strength reassuring us. Yet it felt like dumsor back home — only worse. A blackout without even a candle of connection.

Then came a glimmer of hope. Thawanda made frantic calls, pulled strings, whispered reassurances we barely believed. By some miracle, a commercial international flight was cleared for departure.

As the plane lifted off the runway, I looked down at Zanzibar and thought about the people who couldn’t just fly away — those who still lived in that silence.

At the debriefing, we heard harrowing stories. Some colleagues had slept in their drivers’ homes. Others fled, leaving their bags behind.

By the time we regrouped in Dar es Salaam, my mind was already on home — Ghana — and how much I suddenly valued its noisy, chaotic, yet free democracy.

It wasn’t until I reached Addis Ababa, en route to Accra, that my phone came alive — hundreds of messages from worried family, friends, and colleagues asking where I was.

I’m home now, but Tanzania lingers in my thoughts. Elections, I’ve learned, aren’t just about ballots. They’re about freedom — the freedom to speak, to choose, to hope without fear.

Tanzania’s 2025 elections failed that test.

Latest Stories

-

Weak consumption, high unemployment rate pose greater threat to economic recovery – Databank Research

49 minutes -

Godfred Arthur nets late winner as GoldStars stun Heart of Lions

1 hour -

2025/26 GPL: Chelsea hold profligate Hearts in Accra

1 hour -

Number of jobs advertised decreased by 4% to 2,614 in 2025 – BoG

2 hours -

Passenger arrivals at airport, land borders declined in 2025 – BoG

2 hours -

Total revenue and grant misses target by 6.7% to GH¢187bn in 2025

2 hours -

Africa’s top editors converge in Nairobi to tackle media’s toughest challenges

3 hours -

Specialised courts, afternoon sittings to tackle case delays- Judicial Secretary

3 hours -

Specialised high court division to be staffed with trained Judges from court of appeal — Judicial Secretary

4 hours -

Special courts will deliver faster, fairer justice — Judicial Secretary

4 hours -

A decade of dance and a bold 10K dream as Vivies Academy marks 10 years

5 hours -

GCB’s Linus Kumi: Partnership with Ghana Sports Fund focused on building enduring systems

5 hours -

Sports is preventive healthcare and a wealth engine for Ghana – Dr David Kofi Wuaku

5 hours -

Ghana Sports Fund Deputy Administrator applauds GCB’s practical training for staff

6 hours -

Ghana Sports Fund strengthens institutional framework with GCB Bank strategic partnership

6 hours