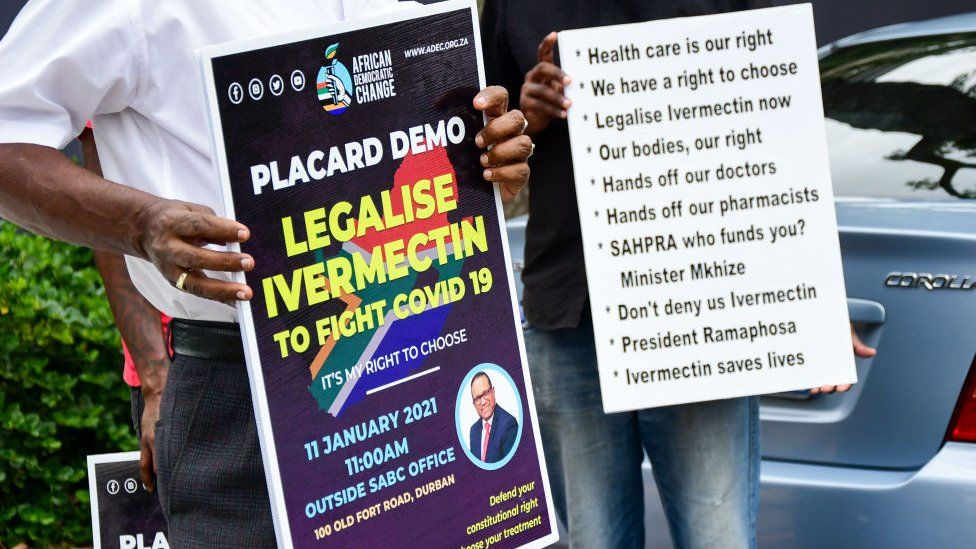

The drug Ivermectin, which has been touted by some as an effective coronavirus treatment even though it is clinically unproven, is at the centre of a legal battle in South Africa as some medics want it licensed for human use, as Pumza Fihlani reports.

Many South Africans are desperate for something that could ease the impact of a predicted third wave of coronavirus infections.

With a vaccination programme that has not yet covered all the most vulnerable, there are concerns that the continent's worst-hit country could suffer more as the temperature cools down with the approaching winter.

More than 52,000 people have died with coronavirus and though new infections are now low, they are not disappearing.

It is in this context that Ivermectin - a drug that is used to treat parasitic worms - has gained a lot of attention. Some doctors have been prescribing it to patients with coronavirus, saying that they have seen anecdotal evidence that it can alleviate some of the worst effects of Covid-19.

However, South Africa's medical regulator, the drug's manufacturer and some of the country's most eminent scientists have all warned against using it to treat coronavirus.

It has now become popular on the black market - millions of tablets have been intercepted in South Africa since the beginning of the year with the illicit network extending as far as China and India.

Before the link to coronavirus was made, 10 Ivermectin pills would cost about $4 (£2.90) - the price has now increased 15-fold for the same packet.

But the use of Ivermectin for coronavirus treatment has divided opinion in the country.

The pill is currently not licensed for human use by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (Sahpra), it is only registered to treat parasites in animals.

Despite this, some doctors began using the drug at the peak of South Africa's first wave in July last year.

'People were dying'

Prof Nathi Mdladla, the head of the intensive care unit at Durban's George Mukhari Academic Hospital, is one of a handful of doctors who have been calling for the use of Ivermectin in desperate cases.

"At the height of the first wave, a lot of hospitals both public and private and GP practices in South Africa were using Ivermectin," Dr Mdladla told the BBC.

"People were dying and doctors were looking at many treatment options to try and save lives. Ivermectin was one of the drugs doctors repurposed."

The idea had come from Latin America where doctors in some countries were using it. More recently, some studies have suggested it could be effective but more research was needed.

But it was not until the second wave late last year that the authorities got wind of this and clamped down on its use, forcing doctors who had been prescribing it to stop, fearing sanctions from the authorities, Dr Mdladla added.

He believes this response has been unhelpful, particularly to families who cannot afford the pricier treatment options.

Now, advocacy groups, doctors on both sides of the debate and Sahpra will have to make their case before the Gauteng High Court in a hearing scheduled to happen soon.

"The fight is about the quality of the studies that have been done so far. What we're saying is that in a pandemic, you can never be in a position to actually generate these high-level, long studies, because it means in the meantime, you watch people die," says Dr Mdladla.

Doctors advocating for it to be allowed locally in the treatment of coronavirus say that the medicine poses no major safety concerns.

Some common side effects include dizziness, nausea, diarrhoea, stomach pain, nausea and skin rash, according to the US Food and Drug Administration.

In South Africa, it has been used on animals but has only been recommended for human use by the World Health Organization to treat river blindness.

Nevertheless, Sahpra is worried that there is not enough research on how it affects patients suffering from coronavirus and is therefore wary about signing off on its widespread use.

In December, it prohibited the use of the drug on people unless doctors get approval through a special "compassionate use" application - this allows an unauthorised medicine to be prescribed in dire situations.

If it is used in these cases then doctors need to provide information on how the patient is responding.

One theory for why it might appear to be effective in patients with coronavirus is that it could actually be treating any parasites they are carrying and so make them stronger, without actually tackling the virus which causes Covid-19.

But in any case, South Africa's medicines regulator warned that: "There is insufficient evidence for or against the use of Ivermectin in the prevention or treatment of Covid-19."

Sahpra also expressed concern over the use of Ivermectin sourced from the illegal market, saying the "quality cannot be guaranteed".

Its manufacturer, Merck, has also warned against the use of the drug to treat coronavirus, saying: "We do not believe that the data available supports the safety and efficacy of Ivermectin beyond the doses and populations indicated in the regulatory agency-approved prescribing information."

It is something Prof Abdool Karim, one of the doctors leading South Africa's coronavirus response, has also highlighted.

He says that the doses being given to people may even be toxic.

"It must be clearly stated that Ivermectin does not kill the virus at dosages humans can tolerate. The amount of drug needed to kill the virus is toxic to humans. Whatever it is doing, it is not killing the virus," TimesLive website quotes him as saying.

'Ivermectin needs to be tested'

Another health expert, critical care specialist Prof Rietze Rodseth, says more research is needed about ivermectin and that there are more questions than answers at this stage.

"I'm quite surprised by everybody's petitioning and going on about the wonders of this drug. The evidence base and quality of the studies done so far are pretty weak. We simply do not have enough evidence to say: 'Yes this works.'" he told the BBC.

"Just because you know the drug, [it] doesn't mean it gets a free pass, it needs to be tested," he added.

It could now be up to the courts to decide, but while the legal wrangle continues, people are likely to continue to try and source the drug on the black market, reflecting a level of anxiety among the population.

Latest Stories

-

Trump criminal case: Full 12-person jury seated in Manhattan

10 mins -

Israel Gaza: US again warns against Rafah offensive

13 mins -

Man arrested in Poland over alleged Russia plot to kill Zelensky

17 mins -

Over 100 arrested as US college Gaza protest cleared

19 mins -

Justmoh Construction begins work on dualization of Takoradi-Agona Nkwanta road

31 mins -

MGL visits Dumor family following passing of Mawuena Trebarh

42 mins -

In Pursuit of Peace and Unity: Interfaith Leaders Promote Dialogue – Chief Doli-Wura to Africa Union

1 hour -

TEWU raises concern over quality of food served in SHS

2 hours -

Ghanaian students gear up for Robotics World Championship

2 hours -

Political interference makes public sector managers appear incompetent – Dr Manteaw

3 hours -

Police arrest truck driver alleged to have caused train crash

3 hours -

CAF Confederation Cup: Dreams FC depart to Cairo ahead of semis first leg against Zamalek

3 hours -

Liverpool exit Europa League despite 1-0 win over Atalanta

3 hours -

Roma beat Milan to set up Bayer Leverkusen clash in Europa League semis

3 hours -

Mohammed Kudus’ West Ham suffer Europa League elimination

3 hours