The two great men – Otumfuo Osei Tutu II and Sir Sam Jonah de-robed their respective majesties in the presence of each other.

Sitting next to each other, at the moment they spent together; they were not the king of Asante and king of the mines. Instead, they were two boisterous boys sharing a bro code as they used the occasion of his 70th birthday last year to transport themselves back into times – back to the teenager years.

Asantehene wearing a wide smile, told the story while Jonah filled in the memory gaps. In the streets of Obuasi, Sam Jonah, a young boy, had bought a car for ¢17, no small money at the time, now only useful for a child’s feeding fee for some three days.

“We named the car Ama Serwaa” Asantehene said.

“He didn’t know how to drive. I didn’t know how to drive. But we were driving” Otumfuo, standing, turned to his side to look down at Jonah.

The ¢17 car suffered some mild crashes, as the boys learned by experimentation. The two boyhood friends lived in what the Asantehene described as “the permissible transgressions of adventurous youth”. At that time, a knighthood in the UK in 2003 was far away.

But what was close to him in Obuasi was a dirty, deep, dark and deadly hole called a mine. That was where the boy born November 19, 1949, in Kyebi would start in working life.

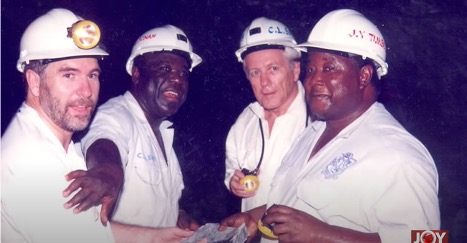

Obuasi, is an Akan word for ‘under a rock’, and in that town, that was what most young people saw the futures – under a rock. But, of course, it was the illiterate blacks who went under the rock. The white managers stood over it as the ore was brought to the fore.

That was the future of many youths – going down. “You did not see yourself going beyond them,” Jonah said. “Mining was associated with death, and safety was not fashionable.’

As many youths escaped their father’s farms after getting some education, it was a general expectation that once Jonah had an education, he would escape the life of a segregated mining community and find something fashionable about the times. Maybe a lawyer in post-colonial Ghana.

But after Adisadel College, while his friends fancied white-collar jobs, Samuel Kelvin Esson Jonah had his own ideas of how to reach the top, he literally went down.

Sam chose to join an illiterate army of black migrants, interning in the Obuasi mine. Some years on the job, he would gain a scholarship to Carbone School of Mines in the UK.

He would go back again to get a Master’s in Mine Management at the Imperial College of Science and Technology.

Ghana was high on the rhetoric that the black man is capable of managing his own affairs. And here was one black man, a poster boy for black mining power in the country.

And so, when Jonah landed back in Obuasi mines, he had come like a wrecking ball, smashing into the cabal of white management.

Sam, in his 30’s would become the first black General Manager and later become the first black Managing Director of Ashanti Goldfields Corporation. Under his leadership, AGC would grow from a single mine in Obuasi to operate three other mines in this country and three others outside the country, in Tanzania, Guinea and Zimbabwe.

The company would be listed on the London Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange in addition to two others.

“Sam came into Ashanti and revolutionized the company. He really broke some of the barriers that existed between the foreigners and the locals.”

“He really empowered our local workforce. He provided training, sent them out. He really changed the face of Ashanti and in a way that had never been done before.”

While Jonah plucked well-educated Africans to join, there was an aspect of Africanisation that was feminization. Mona Quartey, who joined as head of treasury, didn’t need to go to the canteen to see a woman working at AGC. She saw them in the accounts department, in the metallurgy department; some were geologists, truck drivers and even board members.

1996 – more than 25years ago.

But Sam Jonah would face a crisis that defined his time at the mining company. In 1999, gold prices had been experiencing a battering decline. That August, it was going for $252 per ounce – the lowest in 20years at the time.

On the advice of Goldman Sachs, AGC hedged the price of gold to protect it from worsening decline on the international market. Then the price of gold began to rise, hitting $362.25 per ounce in October. AGC hedging meant it could not benefit from the increasing prices. Its profit was shot.

The company’s management faced a crisis. And the knives were out. Shareholders sued. The government sued.

“It got to the point that when we were about to make an important agreement, the chairman of the board was sacked, mining minister sacked, plus the guy in charge of the mineral commission,” a former manager, James Anaman, recounted the dramatic days of the crisis.

The looming collapse had a sort of déjà vu to it. Many years before, when Sam Jonah was a supervisor, he recalled how the roof of the mine caved in and remembered the brave effort he and the others put in to save their colleagues.

He remembered the effort it took to push off a huge rock that had crashed into a Fante miner. As supervisor and leader in the mines, Sam Jonah would help the fatally injured man out of the mine through a lift. His words to Jonah then in his 20’s was ‘thank you very much’.

Some two hours later, word would come in that the man had passed.

Now faced with a hedging crisis that had plunged through the roof of Ashanti Goldfields Company, the bullion-rated question was whether AGC was going to die under the leadership of its poster boy of African capabilities.

“Sam tended to be a fairly optimistic person, tended to see the humour in difficult situations”, Kweku Awotwi, who worked at AGC, would say. The AGC’s head of investor relations at the time, James Anaman, would remark that during a flight after the pilot had announced some difficulties, Jonah would look at him and laugh at his fear of “small death”.

AGC survived death by bankruptcy, backed by the company’s bankers despite distrust from some of its investors.

In June 2003, the Queen of England, Queen Elizabeth, who is the leader of the Commonwealth, conferred an honorary knighthood on the Ghanaian businessman who had become an international public figure. Under his leadership, Ashanti Goldfields had listed on four international stock exchanges, including the prestigious New York Stock Exchange. In addition, he was serving on United National Office for Project Services (UNOPS) and was advising governments, such as those of South Africa and Nigeria.

It would take some five years after the hedging crisis for the company to put that whole episode behind it. Then, finally, AngloGold Ashanti would find a significant partner. On April 26, 2004, and approved a $1.8bn merger with South Africa-based AngloGold that would create AngloGold Ashanti Ltd, the second-largest mining company globally, with Jonah as Executive President.

Sam Jonah has sat on 18 boards worldwide and has been named one of the greatest Africans by Havard University and has received five lifetime achievement awards, the first coming in the ’90s.

He paid tribute to his father's influence, a war veteran, a disciplinarian carved in the mould of a soldier in an era of feared fathers.

“He talked to us as if he was commanding us. He had forgotten that he was not a soldier.” It was his father who ingrained in him the habit of waking up at 5 am. Any extra time in bed was time-wasting, his father would say.

His dad, Thomas Jonah, would fetch cold water in his hands from the fridge and rub it off the face of his dozing children – cold enough to banish sleep. It was a “rude shock”

Sir. Sam Jonah said his father despised idleness. “He got pretty upset when he came home, and you were idle”. And so, his children,10 of them, would find something to do with their time, holding a book or doing some chore – two activities that put out any billows of his father’s anger.

Sam Jonah said his punctuality was another stamp of his father, who usually would quip that “it was the passenger who waits for the train and not the train for the passenger.” Under his father’s training, “it is not possible to be late for any event.”

Preparing early for any event is second nature for Sam. And that’s why when life’s train pulled up at the station, young Sam at 30 had prepared himself for a ride that has taken him around the many nooks and cranny of global business. Finally, at 71 years, he has disembarked at a quiet station.

And while that great roller coaster train of his life is gone, Sam Jonah at 5 am would be up and out of bed, waiting for another train albeit, a less pacey one.

A train of life would see him put in some four to five hours of work at Jonah Capital, an equity firm he founded. A train that would slow down enough for him to play his favourite golf, play the piano and consuming TV content,

“I have now added swimming,” the 71-year old international business leader told JoyNews’ Raymond Acquah during the filming of Ghana’s Greats.

Swimming. Sam has made some deep swims in his challenging career, which he admits included many failures, with the only constant being his unwillingness to give up. So a small pool of water shouldn’t be too hard.

Latest Stories

-

11 troubling signs of emotional distance in a relationship

1 min -

It’s good justice has finally been served – Martin Kpebu on sentencing of ex-MASLOC CEO

36 mins -

Higher Life Chapter @ Ten: Church earmarks spirit-filled activities to celebrate anniversary

2 hours -

Introduce a levy to resource Mental Health Fund – Stakeholders urge government

2 hours -

Angry Kotoko fans storm Adako Jachie to prevent Prosper Ogum, players from training

2 hours -

ECG lied about Transformer overload being responsible for power outages – PURC

2 hours -

Fuel price increase: Petrol selling at GH¢14.99, diesel going for GH¢14.80

3 hours -

Adoagyiri Zongo chiefs call on Okyehene, reaffirm allegiance to Okyeman

3 hours -

Ghana’s emerging economic potential – Ekumfi and Natural Juices Industries

3 hours -

Global economy resilient; to expand by 3.2% in 2024 – IMF

3 hours -

NDC takes on Akufo-Addo over renaming and relocation of Ameri Power Plant

4 hours -

First product of Meghan’s lifestyle brand revealed

4 hours -

West African leaders dial down on Togo mission

4 hours -

Season 5 of BMPS Show on Joy Prime takes off on April 18

4 hours -

Election 2024: EC opens applications for various positions

4 hours