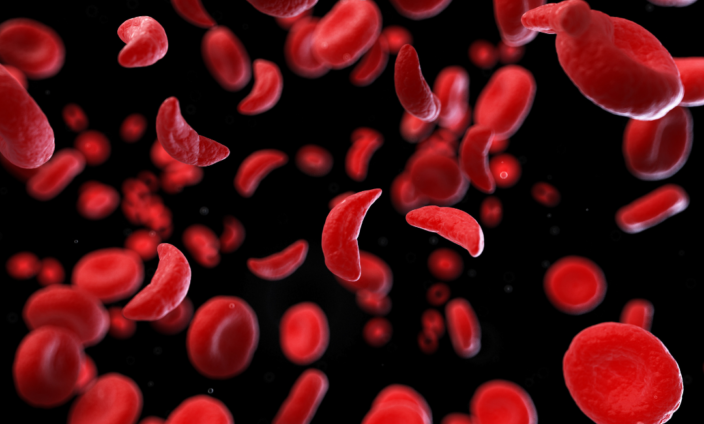

About 400,000 African babies a year are born with sickle cell disease (SCD), a genetic blood disorder. Nigerian researchers calculated last year that these babies are four times more likely to die before their fifth birthday than children without SCD[1].

Before modern treatment, few reached adulthood[2]. Yet, Ghana has shown that things do not have to be this way: if we can diagnose these babies early and treat them, most will live full lives and contribute all their gifts to our society[3].

Soon, we expect even better treatments that will go a long way to eliminating the pain, infections and long-term disability that has so often been associated with SCD in the past.

As a patient advocate for 13 years, I have come to understand that the biggest gap is knowledge. Education can help dispel the myths and stigma that surround SCD. It also helps manage the distress of parents and make sure that children go to school and achieve their full potential.

However, what we have learned from the early days of HIV in Africa is that families will not come forward for diagnosis if there is no hope of treatment. Would you want to know that your child faced a short life, full of pain and infections, if there was nothing you could do about it?

Now that effective HIV treatment is widely available, many more are willing to be screened. Education, as we saw in HIV, has to go hand in hand with screening, access to treatment and steady research on treatment advances. Stigma disappears, lives return to normal and society is sustained.

This screening and early diagnosis is critical: it is what gets children into treatment and permits them to learn, socialise and develop. If children are diagnosed late, they will already have missed important milestones and are at increased risk of death: in California, only 1.8% for children diagnosed with SCD through neonatal screening died when compared with 8% for those who were diagnosed after presenting with symptoms in the pre-screening era[4].

It needs to become a standard procedure across the continent.

Too often, though, that diagnosis of SCD seems terrifying. I recently took part in one of a series of webinars on SCD organised by Novartis, a global medicines company. Dr Frederick Otieno Okinyi of the University of Nairobi explained the impact of SCD on the family.

“The complications of SCD cannot just be viewed in numbers, we can really view them in terms of socioeconomic and psychological impact. The parents of children with SCD typically have poor progression in their careers, and spend much of their income caring for their children with SCD [while their] children cannot perform activities like others due to pain and constant appointments.”

the Children are often not allowed to do all that they could. Arafa Salim Said, a Tanzanian who is one of my fellow SCD advocates and a person living with SCD, described a situation that I see all too often.

“Many people do not understand that a child with SCD can still go to school and should achieve their goals. They believe that a child with SCD is fragile, and that they should simply sit and do nothing and wait for their day to die…Finding work is often difficult, as employers believe the individual will miss a lot of days.”

Today, this is not the experience of people with SCD in Europe, North America or even in emerging economies such as Jamaica.

The American Centers for Disease Control advises that, “People with sickle cell disease can live full lives and enjoy most of the activities that other people do…Sickle cell disease is a complex disease. Good quality medical care from doctors and nurses who know a lot about the disease can help prevent some serious problems."[5]

In Africa, we can achieve similar results, but as Arafa told that webinar, we must first recognise that, “a person living with SCD is still a human being, they have all the rights to school, work and marriage anyone else has.” Then we have to act on that recognition.

Pilot programmes in Ghana have shown that we can improve the lives of Africans with SCD just as other societies have done. Ghana screened half a million babies. If a diagnosis of SCD is confirmed, they were entered into a database, parents were informed and preventative antibiotics were provided.

Now, hydroxyurea, the standard of care, is also offered and it reduces the number of painful crises that patients experience when their malformed blood cells can’t deliver enough oxygen around the body.

Working with the American Society of Hematology, the app used for early diagnosis and to monitor the course of treatment will be rolled out in six other countries and more are on the way.

“It is important that we are able to know early on,” Dr Lawrence Osei Tutu of the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital said in the webinar series.

“Screening can confirm, at birth, whether a person has SCD and then we can enrol that child in a care programme very early before the onset of the symptoms so that they do not develop into chronic complications” or die young. It also means that special attention can be paid to the child’s nutrition and exposure to infections.

These pilots need to be extended to cover the whole country and, indeed, the whole continent. As the Former CEO and President of the Global Alliance of Sickle Cell Disease Organizations, I’m extremely proud of our network of patient activists -- a professor, who was one of my fellow panellists said, “the patient network groups have been the best advocacy groups I have ever seen.” But, we need the support of the whole of society if people with SCD are to get their fair share of resources.

As diagnosis becomes more common, as treatment works, as children with SCD survive and thrive and as people with SCD contribute to the African century, stigma will dissolve and parents will routinely ask for their children to be screened. I’m a psychologist by profession and this is what we -- and what engineers in their field -- refer to as a self-reinforcing feedback loop: as something becomes more and more common, it finally becomes the normal behaviour in society.

Imagine a Ghana where we don’t lose -- or cocoon -- one in 50 of our children. Imagine an Africa where many go on to become leaders, scientists, preachers and a hundred other roles that build our society.

Imagine each of these precious children, made in God’s image, enjoying dignity and fulfilment they deserve. You can help make this happen by educating yourself, talking to our elected representatives about SCD and insisting that the capacity be there to screen early for SCD, and to deliver treatment.

Author: Dr. Mary Akua Ampomah is a Former CEO and President of the Global Alliance of Sickle Cell Disease Organizations (GASCDO)

[1] Nnodu O, Oron A, Sopekan A, et al. Child mortality from sickle cell disease in Nigeria: a model-estimated, population-level analysis of data from the 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(10):e723-e731.

[2] Grosse SD, Odame I, Atrash HK, et al. Sickle cell disease in Africa: a neglected cause of early childhood mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(6 Suppl 4):S398-S405. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.013

[3] Piety N, George A, Serrano S, et al. A Paper-Based Test for Screening Newborns for Sickle Cell Disease. Sci Rep 7, 45488 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45488

[4] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajh.24235

[5] https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/healthyliving-living-well.html

Latest Stories

-

19 steps for getting over even the most devastating breakup fast

4 hours -

8th Ghana CEO Summit launched with focus on AI transformation, economic diversification

4 hours -

Prof Opoku-Agyemang has not been given a fair appraisal – Ablakwa

4 hours -

Rainstorm wreaks havoc in Keta and Anloga districts, residents count their losses

4 hours -

Global Plastics Treaty negotiations begin in Ottawa as countries converge on phasing out problematic plastic uses

5 hours -

Support energy alternatives adoption to sustain businesses – GUTA tells government

5 hours -

11th DRIF opens in Accra with a call on governments to focus on digital inclusion

5 hours -

Stakeholders outline plans at RE4C Coalition’s General Assembly in Accra

5 hours -

Women Need ‘shock observers’ for active political participation – Ex-Bauchi Assembly Member

5 hours -

2024 polls: Stop fighting over positions in Mahama’s next government – Asiedu Nketiah

5 hours -

Although people may not always listen to the lyrics, there’s still a market for rap in Ghana – E.L.

5 hours -

Passengers appeal to transport operators to officially announce new fares

5 hours -

Damongo: About 400 NPP Members resign over Minister’s alleged meddling in chieftaincy affairs

6 hours -

Next NDC government will pay special attention to women – Naana Opoku-Agyemang

6 hours -

Amerado is singing and it’s good he’s doing that – Lyrical Joe

6 hours