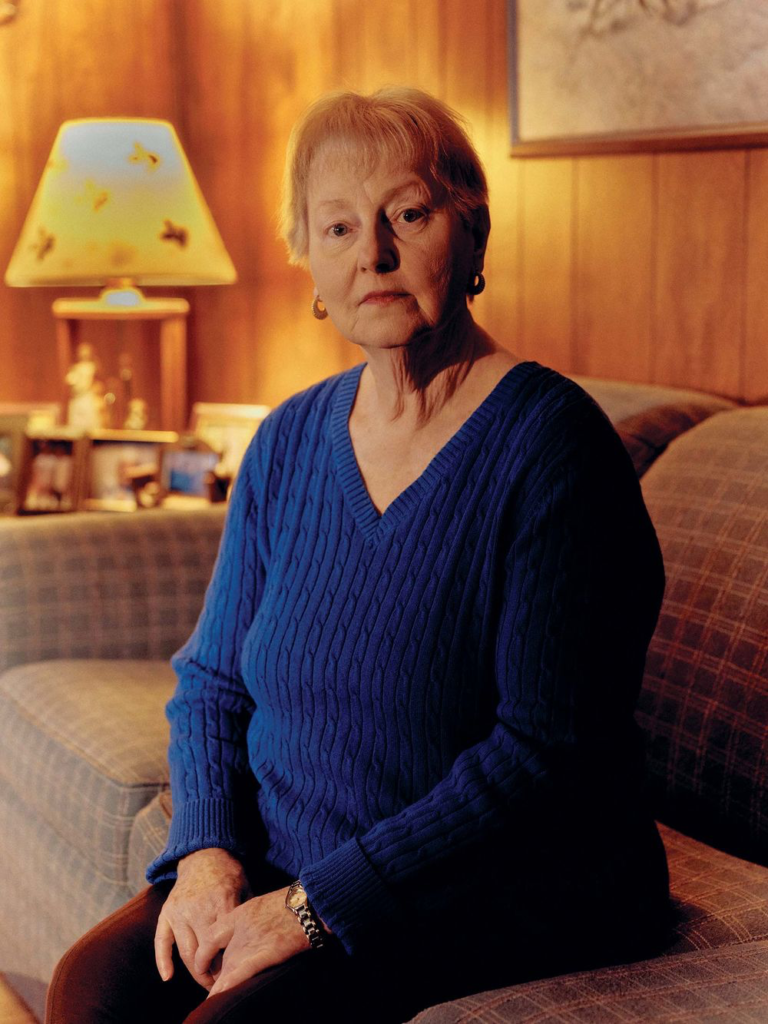

Linda Provence has lived in the same neat brick ranch house in Bedford, Texas, just outside Fort Worth, for more than 50 years. On the wood-panelled walls of her living room hang black-and-white photos of her mother and father, who abandoned her as an infant, and of a company of Texas Rangers, circa 1887, in wide-brimmed hats with long guns.

It’s said that Fort Worth is where the West begins, and these images—like the lasso hung decoratively over the couch and the bucking bronco sculpture on the mantle—speak to the ethos of self-reliance that’s especially cherished in this part of the state.

Provence was born in rural Paris, Texas. When she was 12, she came to live in Fort Worth with her aunt, a nurse, and uncle, a milkman. She married and raised two children. In 1992, after her husband ran off with a high school sweetheart, Provence was left with a lien on the house and crushing credit card debt.

She took jobs at Dillard’s, as a cashier, and with Citigroup Inc., in customer service, where she worked for 18 years, paying off the house and her Honda. “I was proud of myself for that,” she tells me on a recent visit.

Photographer: Jake Dockins for Bloomberg Businessweek

Around 2008, Provence learned that her aunt and uncle had left her an inheritance of about $350,000—a fortune, to her thinking. She kept some of the money at Wells Fargo, where her relatives had banked, and distributed the rest among investment accounts at Chase Bank, Allstate and Thrivent, a Christian nonprofit. Provence doesn’t have expensive tastes. In her spare time, she enjoys country-western dancing at a local senior centre, and her bucket list includes seeing honky-tonk legend Dwight Yoakam in concert. But her money was growing slowly, and she wanted to help her children and grandchildren. Provence decided that having her investments all in one place, earning the same interest rate, would be easier to manage.

One day she mentioned this to a local tax preparer. “Have you heard of Doc Gallagher?” the preparer asked. Provence had. William Neil Gallagher, the owner of Gallagher Financial Group Inc., a financial planning firm, had an office in Hurst, practically down the road from her home. He also had a long-running show on Christian radio. Provence had never paid him much attention, but his name soon seemed to echo in her ears. A friend at the senior center mentioned that she and her husband had invested with Gallagher. An acquaintance from her church endorsed him, too.

After attending one of the free informational dinners Gallagher held at local restaurants, Provence went to see him at his office. A former high school basketball player, Gallagher, then in his mid-70s, had taken up swimming and marathons later in life. He was broad-shouldered, with a sweep of thick silver hair and the ghost of a Boston brogue. “He was very charismatic,” Provence says. “Nice and knowledgeable and sincere.”

“I felt like I could tell him anything. And he would pray with me”

Gallagher told Provence about his Diversified Growth & Income (DGI) program. By depositing her money into five categories of investment—Treasuries, third-party life insurance settlements, fixed index and what he called Investors Business Daily Formula and, separately, Value/Dividends—he could get her a 5% annual return, he explained. And he promised a 5% bonus on top of her initial investment just for signing up.

Provence thought of herself as skeptical, even suspicious. “With the rough childhood that I’ve had, it’s made me a strong person,” she says. “I’ve never been trusting of anyone.” But she was impressed with Gallagher’s financial savvy, the polish of his office and his devotion to Christianity: “I felt like the Lord had led me to him.”

During 2016, Provence moved almost all of her savings to her DGI account. Her esteem for Gallagher only increased. He and his wife, she learned, were involved in charities and had adopted two grandchildren when their daughter couldn’t care for them. From time to time, Gallagher would send Provence flowers or a gift card for Walmart or Home Depot. After she’d skimmed a Billy Graham coffee table book at his office, she was delighted to find a copy delivered to her house. Provence confided in Gallagher when she was having family troubles. “I felt like I could tell him anything,” she says. “And he would pray with me.”

In 2019, Provence’s daughter opened a DGI account, too, investing about $140,000 with Gallagher. But when she looked at the binder of materials he gave her, it contained a portfolio of his accomplishments and good works—press clippings, a copy of a letter from former Governor Rick Perry, photos of Gallagher serving pancakes to the poor—rather than financial documents.

When her daughter, who asked not to be named, examined her mother’s DGI statements, she found them troublingly sparse, showing little more than Provence’s net holdings and the distribution of her funds into the five investment categories. Curiously, each investment type showed the same balance. Provence realized that, even though her money appeared to be growing as advertised, she had no idea where Gallagher was investing her savings.

“I got to thinking: ‘Shouldn’t I have known the names of these companies that have my money?’ ” she says. “But I was just so proud of myself for getting all my money in one spot and earning 5% interest on it.” Provence asked Gallagher for more information. But by then, unbeknownst to her, her investment was already all but gone—along with tens of millions of dollars more from hundreds of other investors.

Her daughter’s money was gone, too. “That was worse than me losing all mine,” Provence tells me. “For me to refer my daughter for destruction.”

As its name suggests, Fort Worth began as a military encampment. A frontier outpost established in 1849, it became a cattle town and then, in the early 20th century and again in the 1970s, an oil town. Since the 2000s a natural gas bonanza from the Barnett Shale formation, which lies beneath the city, has been underway. Other major employers include American Airlines, Bell Helicopter and Lockheed Martin. With a population of more than 900,000, up from fewer than 750,000 in 2010, Fort Worth is one of the fastest-growing cities in the US.

Despite all this—the din of construction, the looping highway overpasses, the multiplying subdivisions and strip malls and shiny showpiece pickup trucks—Fort Worth continues to think of itself as a small town. In the ’80s, when Gallagher settled there for good, one of the first things he did was buy cowboy boots. Eventually, he’d come to embody the city’s mores and contradictions. His persona could seem perfectly designed to appeal to watchers of Fox News, but it was also a patchwork assembled from his own strange experience of 20th century American life.

Gallagher was born in New York City, the second of two boys. His mother, Rita, was a phone operator during World War II. His father, a firefighter, abandoned the family. Rita and the boys moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where she’d grown up poor in an Irish Catholic household. She remarried to a former classmate, Francis Gallagher, and had another son. Gallagher took his stepfather’s last name but felt little warmth toward him. “Our relationship was noncommunicative,” he tells me. Francis had diabetes, which was exacerbated by drinking. After he left his job as a wool sorter at a textile mill, the family subsisted on welfare, living in tenements. When Gallagher was 15, Francis slipped into a diabetic coma and died.

After graduating in 1963 from Rhode Island College, Gallagher, enamored with John F. Kennedy, joined the Peace Corps, teaching English in a village in northern Thailand. “I wanted to learn to live as a Thai, speak as a Thai,” he says. At a cafe in Chiang Mai, he met an American missionary named Don. After talking with him, Gallagher began studying the Bible—searching, he says, for proof of its falseness. It didn’t work out that way: “The more I read, the more I became convinced it was God’s word. I accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and savior.”

Gallagher returned to the US and hitchhiked from Rhode Island to Texas, where he studied at the Brown Trail School of Preaching, in Bedford. He married a dental hygienist named Gail and got master’s degrees in religion and philosophy. He preached outside Fort Worth and taught at local colleges before enrolling, in the ’70s, to study philosophy at Brown University in Rhode Island. “I felt the Lord wanted me to get a quality Ph.D.,” he says.

But Gallagher struggled to assimilate. He’d undergone another conversion. “Growing up as a Democrat, the view was: The government owes me a living,” he says. “When I came to Texas and saw the pioneer spirit, the entrepreneurial spirit, I saw we are responsible for our success.” At Brown, he later wrote, he’d found his classes to be “brainwashing drills: ‘Government is good; society is bad; people are helpless.’ ” His resentment deepened when, after completing his dissertation, he couldn’t find an academic job. He attributed the failure to affirmative action.

Gallagher had been ministering at a church in Providence, where he and Gail sometimes took in people who needed housing. They’d had two children of their own and adopted a son from an orphanage in India. The family eventually moved to Mississippi, where Gallagher worked for the American Family Association. A Christian fundamentalist nonprofit, the association has orchestrated boycotts against media and businesses for promoting LGBTQ causes, abortion rights and titillating content. Since 2010 the Southern Poverty Law Center has labeled the organization a hate group. But Gallagher, who left prior to that designation, remains proud of his work there. “We pioneered the strategy of going after advertisers for immoral programs,” he says.

Gallagher published How to Stop the Porno Plague: A Simple, Straightforward Action Plan That Can Work in Your Community, a screed trafficking in dubious warnings about child pornographers and progressive-minded speech that prefigured modern extremist talking points. Speaking about the book on radio and TV, Gallagher got a taste of public life. As a panel guest on the national ABC talk show Issues and Answers, he endured what he recalled as an ambush: “a raging ACLU chief, a pompous professor, a scolding journalist, a mocking host.” But Gallagher relished the experience. “When they don’t have an answer,” he later wrote, “they stammer, stutter or run. Or slam the teller of truth.”

Gallagher and his family moved to Memphis, where he became a securities broker for Dean Witter Reynolds (which later merged with Morgan Stanley), and finally to Fort Worth, where he took a similar job with A.G. Edwards (which ultimately became part of Wells Fargo & Co.). He studied under the Texas sales guru and motivational speaker Zig Ziglar and built his business by conducting seminars. Gallagher saw finance as an extension of faith. It was a means of acquiring wealth that he could distribute to charity and of providing clients with independence.

“Even though he wasn’t a preacher anymore, he still had the same values,” Gallagher’s adopted son, Matthew, recalls. “We would still do our Bible study every night. If the kids were fighting, he’d have us all sit down in the living room, talk it out and pray together.”

In the early ’90s, Gallagher founded Gallagher Financial Group, in Hurst, and later opened a Dallas satellite. Before long he was a regular presence on local Christian radio, eventually hosting a show several times a week on four stations. Matthew, who became a certified financial planner and an employee of GFG, joined him as a frequent co-host. (Matthew has never been accused of wrongdoing.)

Gallagher’s show, which went by various names, covered subjects such as 401(k) alternatives and estate planning. But it was heavier on self-promotion and fearmongering than advice. Folksy in manner, Gallagher issued alarmist warnings about market instability, government meddling and the greed of big-city elites. Following economic meltdowns, he said, retirees who’d placed their faith in major brokerages “had to stand in lines to get surplus cheese and bread.” He claimed his own clients lost nothing. With “less government, more personal responsibility and with the help of God,” he offered to provide similar protection to others.

Gallagher positioned himself as a former insider who’d repented for his Wall Street past and could share with clients what others didn’t want them to know. “We don’t work for Los Angeles, Chicago,” he said. Even as he repudiated academia, he emphasized his Ph.D., referring to himself, in an evocation of his advanced degree and the Wild West, as “Doc” Gallagher. Books such as Jesus Christ, Money Master: Four Eternal Truths That Deliver Personal Power and Profitand The Money Doctor’s Guide to Taking Care of Yourself When No One Else Will provided a patina of intellectualism. Photo ops with figures including Joel Osteen, Nolan Ryan and Dallas real estate doyenne Ebby Halliday endeared him to his clientele.

When not in the office, Gallagher was often at the wheel of his late-model Cadillac, visiting clients at home, in the hospital and at church. He liked to quote from Psalms: “This is the day that the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.” Warm and boisterous, Gallagher projected casual confidence. He favored the soft sell. Susan Pippi, a former client, says: “He went about things slowly. He didn’t pressure you.” Some clients saw him as extended family, asking him to speak at weddings and funerals. “I trusted him like a brother,” Pippi recalls. Still, another former client, Yvonne Blackard, noticed that whenever she asked a question about her Diversified Growth & Income account, Gallagher found a reason to leave the room. At a birthday party for her husband, Gallagher stood to speak. “But it was about his financial thing,” Blackard says—a promotional spiel.

Gallagher created the DGI program after encountering regulatory trouble. In 1999 he was reprimanded by the Texas State Securities Board for allegedly falsifying records and representing himself as an investment adviser—he was licensed to sell securities, not give financial advice. Gallagher denied the charges and was fined $25,000. He gave up his broker’s license in 2001.

Gallagher sold his brokerage for an undisclosed sum and refocused his business on nonsecurities investments. But the money from the sale wouldn’t last, and his diminished status seemed to hurt his ego. According to Matthew, his father “wanted to stay a big name. He wanted to stay out there in front of everybody.” Matthew says he questioned spending on large radio buys: “There’s marketing to grow your business, and there’s reasonable costs for that. That’s not what he did. He did marketing for ‘Doc.’ ”

Gallagher didn’t welcome the advice. “He would get very angry with me for questioning him,” Matthew says. He and his dad were close. But Gallagher could be emotionally remote. Matthew sometimes confided in his wife or mother about his frustrations at work. This, too, upset Gallagher, who told his son to compartmentalize: “He would say, ‘You have to be like a policeman. When a policeman gets home, they take off their gun and badge and leave everything in the car. You go in, and it’s a whole different person.’ ”

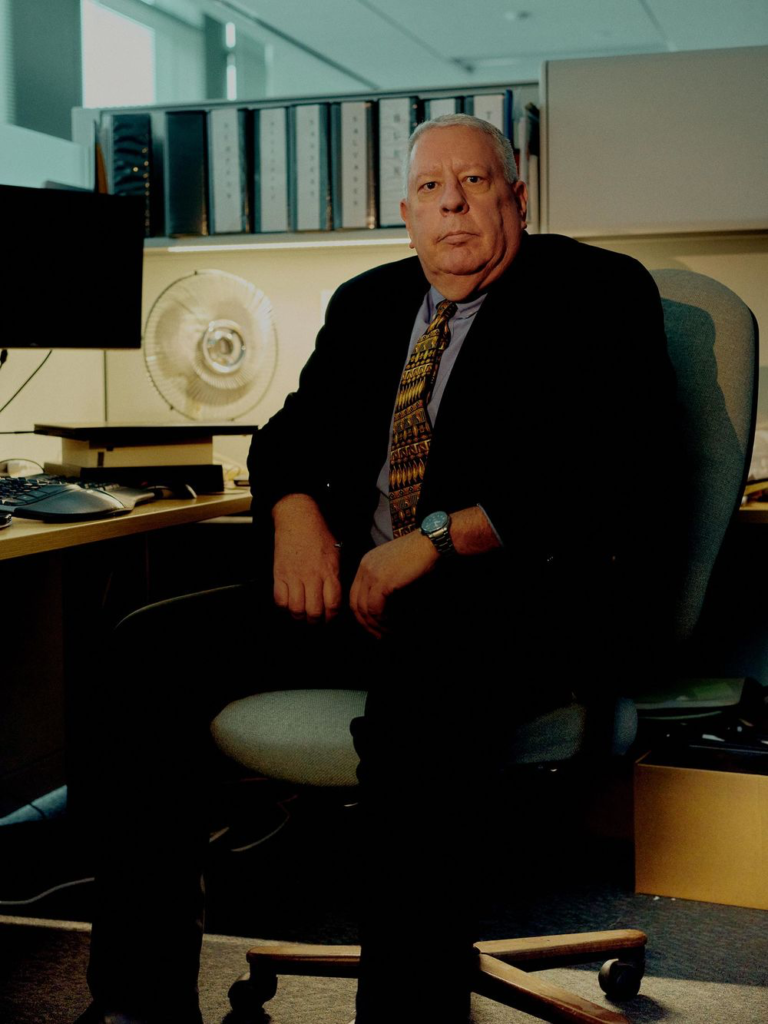

In 2015, Steve Richardson, an investigator with the Texas Department of Insurance, got a call. It was from Barbara Krueger, an investigator at Allianz Life Insurance Co. of North America. Recently, Allianz had received several requests from Gallagher to make withdrawals from annuity investments on his clients’ behalf. In the case of a 92-year-old woman named Doris Fenner, Gallagher had submitted a striking number of requests. The Allianz payments would’ve triggered big early-withdrawal penalties, and Krueger called Fenner’s grandson, Ryan, who had power of attorney, to confirm he was cashing out. Ryan said he’d never authorized the withdrawals, so Allianz hadn’t issued any payments. (Fenner died in 2021.) The circumstances struck Richardson as suspicious, and his office opened a case.

Richardson subpoenaed Gallagher’s bank records, and he saw a pattern. Gallagher conducted most of his business out of one account at a local bank. The records showed several large deposits that were each followed by a few dozen withdrawals, often cashier’s checks made out to Gallagher Financial Group clients. Many of those checks were then redeposited into the same account. This movement of funds—without any intermediate investment in the stock market or other vehicle—amounted, in Richardson’s mind, to evidence of a Ponzi scheme.

Photographer: Jake Dockins for Bloomberg Businessweek

He used Gallagher’s records to identify other clients. Richardson learned that many of them had transferred significant portions of their savings, in some cases cashing out retirement accounts. Most were senior citizens, and virtually all were observant Christians. They often reported receiving regular dividend payments. None had anything bad to say about Gallagher, and some wondered why Richardson was poking around. He recalls: “They said, ‘Why are you asking about this? Gallagher’s a good man. Gallagher’s a man of God.’”

Like Linda Provence, the clients Richardson spoke to were vague about what Gallagher was doing with their money. But they were sure of his character. “They said: ‘He would eat dinner with us. He would pray with us. When I had difficulty with my computer, he would send somebody over.’ ” Gallagher warned against the overreach of regulators in his books and on the radio, and clients reported back to him about Richardson’s visit. “Traditionally in investigations, someone’s upset,” Richardson says. “At this point, I don’t have anyone who’s upset.”

He made little progress for more than two years. Then, in 2018, he got a call from Jim Hobbs, a detective at the Hurst Police Department. Hobbs was familiar with the idiosyncrasies of elder fraud investigations, in which victims often don’t come forward. “There are people who fear that if their family finds out that they’re missing their money,” he says, “they’ll take control of their finances, take away their freedom.”

Some months earlier he’d received an unusual complaint from a couple, James and Carol Herman. They’d shown up in person, and, unlike some elderly victims Hobbs encountered, they weren’t reticent. They were furious. In 2015, James, then a 68-year-old petroleum engineer, was working near Dallas and heard Gallagher on the radio. He and Carol, then 63, had recently discussed diversifying their investments to ensure they could live comfortably in retirement, and Gallagher’s pitch was enticing. After meeting with him, the Hermans emptied their 401(k)s and ultimately transferred almost $700,000 to a DGI account.

Carol, a nurse, suffered an injury in 2017 and could no longer work. She and James, who was by then retired, spoke to Gallagher about doubling their monthly withdrawals. Gallagher initially suggested they instead take out a reverse mortgage on their house—a bank loan, based on the amount of equity they had in the home, to be paid off when it sold. “We said, ‘No way and no how,’ ” Carol recalls. “I became livid.” Soon thereafter she called Gallagher to withdraw $100,000. But he proved uncooperative.

Photographer: Jake Dockins for Bloomberg Businessweek

“Every time I would call and ask questions, he’d send flowers, candy, a fruit basket,” Carol says.

“He told us that he wanted to send us on a trip to the Holy Land.” The Hermans eventually got a meeting with Gallagher in Dallas. They were able to wrangle the $100,000 from him, but he couldn’t provide detailed information about their account. Afterwards they drove to Hurst and spoke with Hobbs.

Hobbs and Richardson coordinated with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Texas State Securities Board and prosecutors in Dallas and Tarrant County, which includes Fort Worth, to get additional records and interview dozens of Gallagher investors. The stories they heard were nearly identical. Few clients sensed anything amiss. But by 2019 law enforcement had gathered overwhelming evidence of fraud.

That March, the SEC filed a complaint accusing Gallagher of misappropriating almost $20 million from about 60 investors. He was soon arrested and pleaded guilty in Dallas to securities fraud, receiving a 25-year sentence in state prison. In an instance of Texas justice, a second plea—to charges including fraud and theft—in a case in Tarrant County earned him three concurrent life sentences. At a 2021 hearing, victims described selling homes and borrowing money from their kids to stay afloat. Susan Pippi testified, “I will never trust anybody but God and my immediate family again.”

He bristled at the description of him as the Bernie Madoff of North Texas: “He had a seaside villa. I didn’t buy yachts, I didn’t take vacations”

Photographer: Jake Dockins for Bloomberg Businessweek

The Dallas judgment required Gallagher to pay $10.4 million in restitution. (The judge in the Tarrant case didn’t order any financial penalty.) But by then his primary bank account held less than $900,000. Tracking down the remaining money known to have been placed with him—a total that rose to $23.6 million, extracted from almost 200 investors—fell to a court-appointed receiver, Cort Thomas. When I visited him at his Dallas law office, Thomas, a preppy Texan in his 30s, said Gallagher’s Hurst headquarters was a mess: “The majority of the stuff was just old mail, a bunch of trash.”

With the help of forensic accountants, Thomas determined that Gallagher had made significant payments to the radio stations where he’d been a host. He was buying airtime, it turned out, but the programs weren’t always adequately labelled as advertising. Thomas reached settlements with them totalling nearly $6 million. He also recovered small sums from, among other vendors and nonprofits, the John Birch Society ($7,400), Hillcrest Church of Christ in Arlington ($4,000) and storage company LTL Management ($3,717).

Gallagher had also funnelled cash to dubious investments, such as an apparently fraudulent gold mining business and a company called Hoverink Biotechnologies Inc., which first purported to be a recreational hovercraft business and later a maker of sci‑fi‑style body armour and miracle cancer drugs. Thomas didn’t manage to recover any money from the mining business or Hoverink, though.

Gallagher didn’t have an extravagant lifestyle—a handsome but unflashy suburban home and a lake house in need of updating—and a substantial amount of money still appeared to be missing. At some point, Thomas discovered a third office that Gallagher kept secretly at LTL. Inside was a large safe. “Your heart starts pounding,” Thomas recalls. “I’ve found the hidden treasure trove!” The safe contained a paper list of gold and silver items, the imprints of which appeared to line its floor. But it was otherwise empty. “Kind of a gut punch,” Thomas says. To date, he’s returned to Gallagher’s investors roughly $6.6 million, about a third of their total losses.

At least some of the money appears to have gone through a woman named Debbie Carter. Gail, Gallagher’s wife, had told Thomas about Carter soon after Gallagher’s arrest. A former securities broker, Carter had worked with Gallagher at A.G. Edwards and later as his employee. More recently she’d been at Daystar Television Network, a Christian channel that emphasizes the prosperity gospel, where she worked as an estate planning specialist, drumming up donations. Carter referred numerous clients to Gallagher, including his biggest, Seabern Tindel, a retired Bell Helicopter employee who invested more than $2 million with him. (Tindel died in 2020.) According to Gail, who more than once hired a private investigator to look into the matter, Carter and Gallagher carried on an affair for more than a decade. Gallagher acknowledges the affair but says in recent years his relationship with Carter was strictly professional. (Carter’s lawyer didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment on a detailed list of emailed questions.)

Around GFG headquarters, Carter was known to some staff only by an alias: Dr. Burnett. She’d made efforts to conceal her financial relationship with Gallagher, Thomas found. At Ciera Bank, where Gallagher did most of his business, Carter had an account, and another in her daughter’s name, on which she was a signatory. Gallagher often deposited large cashier’s checks into the account nominally belonging to her daughter, and Carter would then transfer the money to her personal account. (Carter’s daughter was unaware of the account in her name, according to investigators.)

In a deposition given by a former Ciera employee, Noah Weatherly, he said he once questioned Carter about the pattern, and Gallagher—“a celebrity-type customer in there”—called to berate him. “He was basically yelling at me, telling me that if I ever questioned his employees’ accounts … I need to call him first.” Weatherly added that Gallagher threatened to get him fired: “Then he said a few curse words at me and hung up.”

Thomas had traced additional payments to limited liability companies Carter controlled and others to mortgages linked to her. A lot of cash seemed to flow to purchases of rural properties south and west of Fort Worth, including a 1,096-acre ranch in Dublin. In a note Gallagher sent Carter from prison, he wrote: “What they are looking for is (presumably) millions of dollars I transferred to other people to ‘hide’ my assets. Didn’t happen. The 40K I sent monthly [to Carter and her daughter] … was to buy land for the eventual construction of a free Senior Wellness Center for my clients. Remember?” But nothing in his records suggested such a plan. Ultimately, Carter received at least $1.5 million from Gallagher, according to Thomas’s calculations.

On March 10, 2021, Hobbs signed a warrant for her arrest for theft, money laundering and related crimes. Two days later, he and a police tactical team that included snipers and a drone operator drove up a dirt road to the ranch where Carter was living with her family. (Carter had by then ceded the Dublin ranch to the receiver, who sold it for $2.8 million, and moved to a slightly smaller ranch in nearby Carlton.)

Standing in the front yard in her pajamas, Carter was pleasant and outgoing. She told Hobbs where he and his team could find a stash of gold and silver that included South African Krugerrands, Royal Canadian Mint Leaf bars, Sunshine bars and President Trump coins, with a total estimated value of as much as $300,000. Hobbs says, “She answered all my questions, except whether she was having an affair with Doc.” On that point, Carter told him, “I plead the Fifth.”

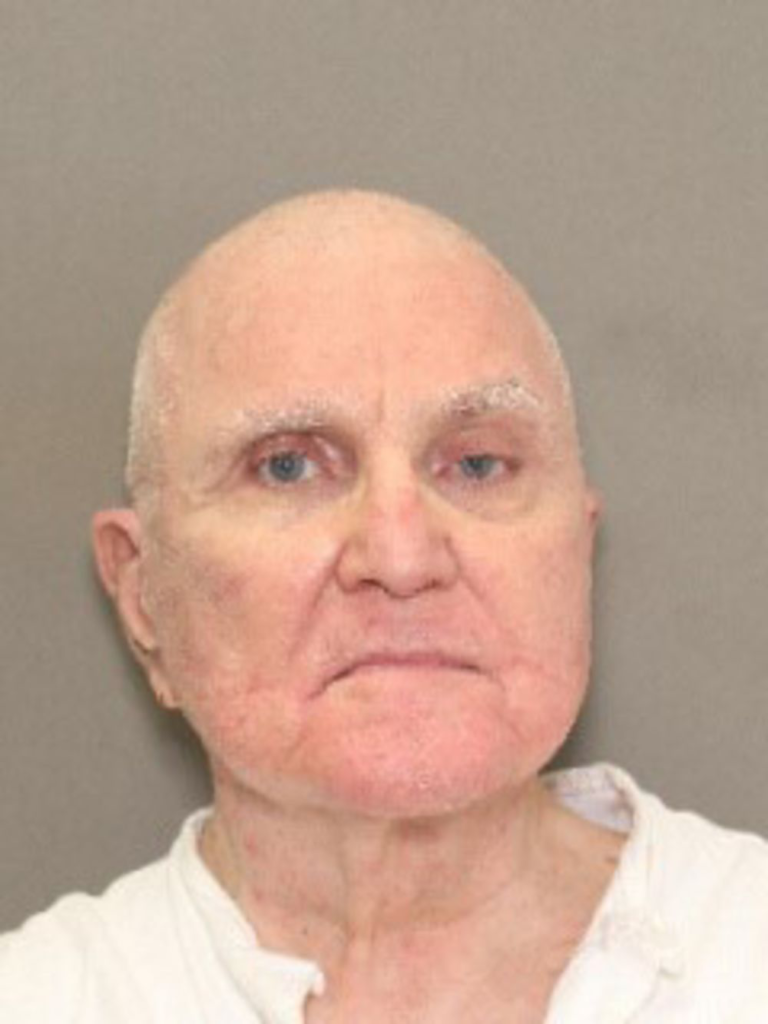

One day last July, I drove 200 miles south from Fort Worth to Navasota, the prison town where Gallagher is incarcerated. It was 110 degrees. Parched rangeland stretched for acres beside the highway, where cattle sheltered beneath stands of trees.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Gallagher entered an area designated for interviews wearing a short-sleeved jumpsuit. Gail had divorced him, and, with the exception of his son Matthew, friends and family had largely abandoned him. Gallagher doesn’t like prison food and rarely has money for the commissary; he appeared shrunken, with thin, liver-spotted forearms. But he was tickled by the visit. “You came all the way from North Carolina?” he asked, his blue eyes shining behind rimless glasses.

Speaking through a screen, Gallagher told me he’d been making friends. “I’m different here,” he said. “A lot of these guys have never finished high school.” On the outside, he said more than once, he was famous. His high profile explained his draconian sentence. But he bristled at the description of him in the Dallas Morning News as “the Bernie Madoff of North Texas”: “He had a seaside villa. I didn’t buy yachts, I didn’t take vacations.”

Unlike true con men, Gallagher insisted, he’d turned crook out of a sense of duty to causes such as the North Texas Food Bank and the Alzheimer’s Association. He claimed that a public offering for the onetime hovercraft company, Hoverink, of which he owned more than a million shares, would’ve netted him $10 million. “It was wrong to borrow that money without clients’ permission,” he said. “But I would have had it all paid back by the end of April 2019.” Yet his records show only relatively small charitable contributions, and there’s nothing to indicate that Hoverink, which went out of business in 2020, had any value. Gallagher later amended his story, telling me he was “conned into putting money into a worthless stock.” Further complicating the picture is that, until 2019, Hoverink’s chief executive officer was Debbie Carter.

One evening a few days after visiting Gallagher, I met Lori Varnell, the Tarrant County assistant district attorney who prosecuted him, at a Cheesecake Factory. She was having a cocktail at a high-top table in the bar. Varnell was busy preparing for Carter’s trial, which is scheduled for September. (Carter hasn’t entered a plea.) Gallagher is expected to testify.

Attached to reports filed in court by Thomas are more than two dozen photos of Gallagher’s offices: piles of paperwork and trash, rumpled clothing, discarded plastic bags, toilet paper, a stick of deodorant. Nothing in them indicates pride or prosperity. In one image, atop a plastic folding table, are manuals with names such as Stay Rich for Life!: Growing & Protecting Your Money in Turbulent Times, The Comedy Thesaurus: 3,241 Quips, Quotes, and Smartass Remarks and On Writing Romance: How to Craft a Novel That Sells. I asked Varnell whether one could be forgiven for wishing that Gallagher had spent some of the money on yachts and vacations—that there had been some clearer point to it all.

“There is or was a goal,” Varnell said. “And the goal was achieved.” She declined to elaborate or talk specifically at all about the Carter case but seemed to be referring to the rural land acquisitions, including the Dublin ranch, outside Fort Worth. In a letter to me, Gallagher wrote: “Any land within 100 miles of Dallas/Fort Worth is (these days) pure gold. What had been ranches were now subdivisions, schools, and stadiums. What had been farms were now shopping malls, amusement parks, and strip-shopping centers. I jumped at the chance to buy that real estate, believing it would double in a very, very short time, allowing me to pay back substantial sums to clients.”

It’s hard to accept this explanation. Until I asked about them, he’d neglected to mention his real estate investments at all. But in its undeveloped state, the ranchland Carter acquired was undeniably majestic: ridges and creeks, grassland and pasture, hunting grounds and lakes.

“Some people think of Bermuda as being their land of paradise—their Beulah land,” Varnell said. “Lots of people think of Texas.”

Latest Stories

-

Bond market: Turnover tumbles by 52.9% to GH¢336.90m

15 mins -

Brilliant Palmer scores four as Chelsea thrash Everton

23 mins -

Cedi depreciates 9.65% to dollar since January 1, 2024, one dollar equals GH13.60

24 mins -

Futsal AFCON 2024: Ghana exits competition after losing to Angola

30 mins -

Ghanaian banks’ profitability to weaken due to new Cash Reserve Ratio regime – Fitch

31 mins -

If physical security cannot be guaranteed, how can election be secured – NDC quizzes EC

2 hours -

Another man jailed eight months over false claims of missing genitals

2 hours -

Youth summit dedicated to environmental education and innovation to take place in Greece

3 hours -

New free, user-friendly platform for tracking marine biodiversity protection now available online

3 hours -

Okoe Boye promises to launch food bank project in Ledzokuku

3 hours -

Bring back inter-schools sports – NSA boss urges GES

3 hours -

Where’s the national cathedral in the performance tracker? – Alex Segbefia asks

3 hours -

Senior Medical Officer urges religious leaders to promote health talks among their followers

3 hours -

Salamta Army takes steps to empower young people in Kpando Municipality on career choices

3 hours -

ASA Savings & Loans donates to Sunyani M/A Basic School

3 hours